It was not the intention of Body No. 12—known, in life, as Mrs. Margaret Rice—to assist in an engineering experiment. An Irish housekeeper heading to Spokane with her four sons (Albert, Eric, Arthur, and Eugene), Body No. 12 was found with few effects: a wedding ring, a set of gold earrings, a ten-pound note, and a half-set of false teeth. None of these are standard laboratory equipment for testing the effect of sulfur on the breaking patterns of steel.

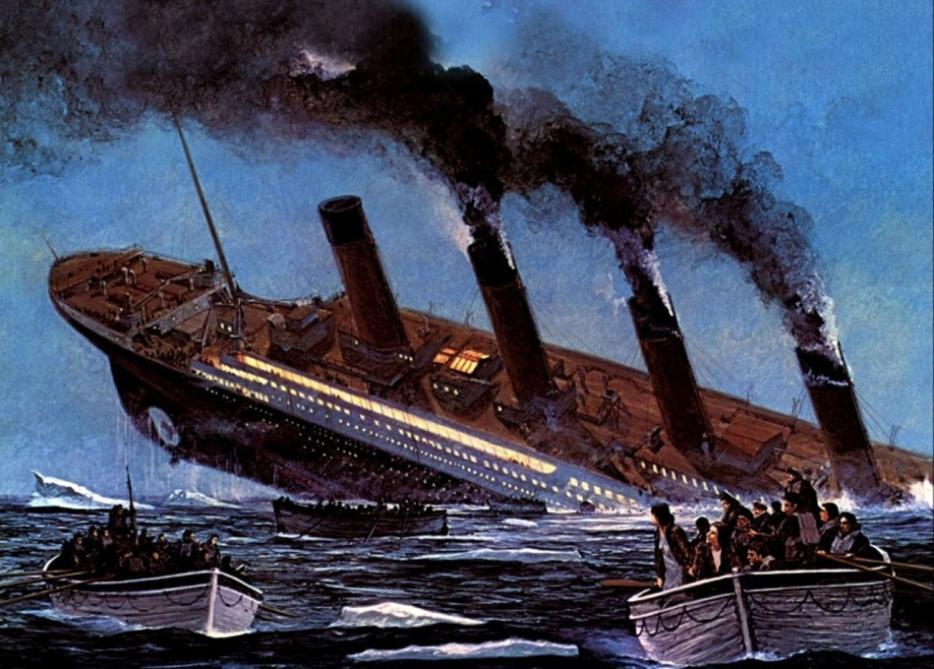

Yet the sinking of the Titanic resulted not only in changes to how ships are built, but in the creation of new lifeboat regulations, a 24-hour radio watch, a clarification of marine communication protocols, and the International Ice Patrol. As Naseem Nicholas Taleb writes in his new book, Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder, “The story of the Titanic illustrates the difference between gains for the system and harm to some of its individual parts.” In this scenario, Mrs. Margaret Rice is the “individual part” and you and I are “the system.” Because she became Body No. 12, I went on a cruise ship last year where I ate oysters Rockefeller and was entertained by Russian aerialists while feeling only a gentle thrum beneath my feet.

It is sickening to profit from other people’s suffering, even unintentionally. But Taleb writes: “[T]he people who perished were sacrificed for the greater good; they unarguably saved more lives than were lost...Every plane crash brings us closer to safety, improves the system, and makes the next flight safer—those who perish contribute to the overall safety of others.” Taleb is not alone in this assessment; his discussion of the Titanic is built on an argument made by engineering historian Henry Petroski, whose 2012 book To Forgive Design: Understanding Failure chronicles the inevitability of design flaws and their ultimately productive repercussions.

In fact, the productively tragic life of Body No. 12 has given us more than double-hulled cruise ships. If you have used a baby’s pacifier recently, you will have noticed two holes on either side of the nipple, each at least 0.2 inches wide and not less than 0.2 inches away from the outer edge of the shield. These are so that even if the baby sucks the guard into his or her mouth, air can still get in and out. When Body No. 12 was a young bride, her first child, George Hugh—born November 30th, 1902—sucked on a pacifier and choked to death.

In this case, improvements to the faulty technology were not immediate—the death of one baby doesn’t register in the collective consciousness the same way the sinking of the Titanic did. But the cause of George Hugh’s death entered the medical record books, another case study in the informal experiment being conducted on pacifier design. It is at the expense of bereaved mothers like Body No. 12 that we have seen the incremental improvements that have introduced those breathing holes. In fact, even Albert, Eric, Arthur, and Eugene would have benefitted from George Hugh’s fatal exposure to faulty design: having lost one child to an ergonomically incorrect pacifier, Body No. 12 would have changed her oversight patterns or abandoned pacifiers altogether—anything to avoid losing another.

Especially after the death of her husband. William Rice worked on the railroad, and in 1910 he was killed in an accident. Forensic engineering is the discipline of gathering information on past disasters, and early rail accidents were the catalyst for the development of fractography—the study of how cracks develop and propagate in material. It’s used to find out why breast implants leak, and why oil pipelines burst.

Where forensic engineering is the science of figuring out what went wrong, risk analysis is the art of predicting what will go wrong. And as usually happens when you compare an art to a science, the art comes off sounding like kind of a joke. In a recent article in the journal Risk Analysis, J. Park et al. write: “Ultimately, where hazards are unknown, risk analysis is impossible... there are always unexpected hazards because an emergent phenomenon can only be observed after it has happened.” In other words, you can only ever cross that bridge when you come to it—and it may have fallen down by then. A more productive path than risk management in engineering systems, the researchers argue, is planning for resilience. Where risk management tries to minimize the probability of failure, resilience planning tries to minimize the consequences of failure—i.e., it takes failure as a given. Instead of gunning for security and longevity, we should set our sights on recovery, renewal, and innovation.

Taleb takes this idea one step further with his term “antifragility.” Resilience, he says, is not enough—what we want are systems that actually get better when they undergo stress. Not only would the ideal Titanic not sink, it would hit an iceberg and become more buoyant. He invites us to imagine a package labelled “please mishandle,” or “please handle carelessly.” It sounds fanciful, but in a 2009 article in Nature Physics, Mark Buchanan wrote about how biological systems seem to have built-in flaws that ultimately make them work better. Of alpha-helical protein networks (filaments within cells), he writes: “cracks in such materials can actually improve their ability to withstand stress... this goes against anything that might have been guessed on the basis of traditional materials science, and offers some ideas for making artificial materials using similar tricks.”

Of course, while we lie on the decks of our ultra-safe cruise ships contemplating the “greater good” that came from the sacrifices of those before us, we too are unwitting participants in any number of experiments. The Russian aerialists will have their contract renewed, but the comedian who told racist jokes may not be asked back next year (at least, I hope not). Some of us will be sunburned, and a number of previously innocent freckles will morph into something worse—treatments will be tested, statistics gathered. Someone will have an allergic reaction after they serve themselves salad from the buffet using a spoon that touched shellfish, and someone else will start work on genetically engineering tropomyosin out of shrimp.

We learn from our mistakes, but we learn best collectively. Like Margaret Rice, we don’t think of ourselves as stepping stones on the road to a world we won’t live to see. It’s an unintentional altruism, the grace the present offers the future.