Is the heavy artillery of theology still aimed at children?

Undoubtedly. I should have a stronger opinion

as to whether this was good or bad for myself or my peers

and, at one time, I did. The teachers were kind.

– John Terpstra, “Cathechism Class”

When I returned from my tour, many people asked me what Germany was like. I said I had no idea. "But weren't you just there?" they inevitably asked. "Yes," I told them. "I was just there. And I don't know what it's like at all."

– Chuck Klosterman

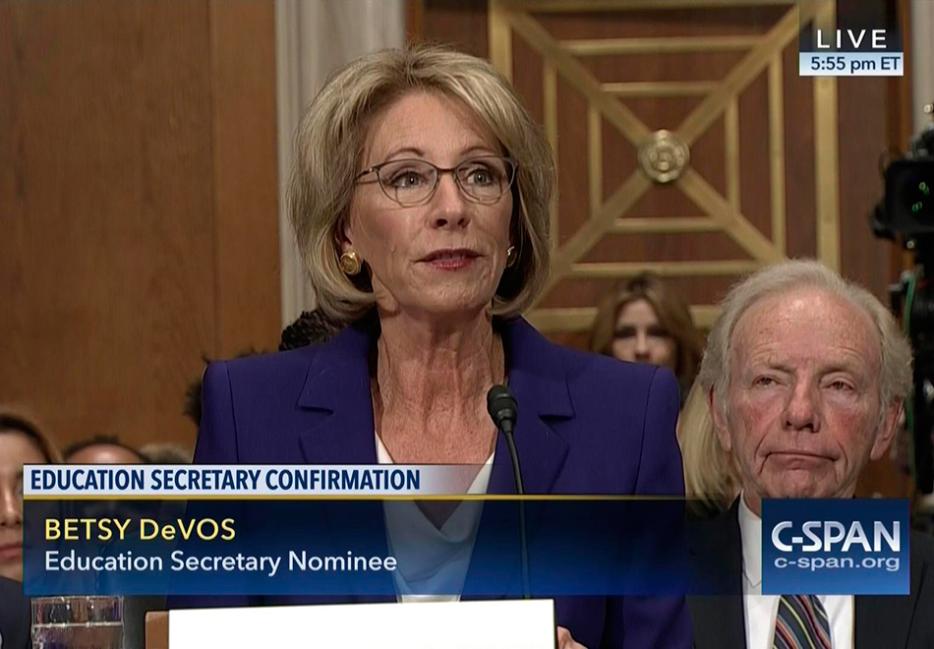

Betsy DeVos, Donald Trump’s new secretary of education, has become a homegrown celebrity from the religion I grew up with. The denomination in which DeVos was formed—the Christian Reformed Church (CRC)—is also the denomination that formed me. She and my mother both went to Calvin College in Grand Rapids, Michigan; my mother graduated in 1972 and DeVos graduated seven years later.

Calvin College is named for John Calvin, that reformer usually associated with his brutal-seeming ideas about elections—that God has known since time began whether you or I or anyone else was predestined for eternal reward or eternal damnation. Connecting lines have been drawn from this doctrine through the work ethic to the prosperity gospel, which, maybe, can connect us to the Amway fortune of DeVos.

My mother never interacted with Betsy DeVos, but she knew of the DeVos family, who contributed money to Grand Rapids renewal and to its CRC schools. In those times it was a kind of family joke to call Grand Rapids “our Jerusalem,” and, though I am keenly aware of how offensive such jokes can sound, it is also the case that the CRC had adopted a sense of chosen-ness and that we strongly identified with the Hebrew people of our scriptures. We were never the sort of Christians who were unaware that Jesus, like most of our Biblical heroes, was Jewish. In the Calvin College of the seventies, some of the students were Michigan residents, wealthy and well dressed, and some of them were homesick out-of-towners like my New Jersey-born mother. Most of them were ethnically white Dutch, a whiteness that has diminished over these years, though Calvin is still reported to be mostly white. Those of us who grew up in the CRC and its schools called it “the bubble.”

*

Everyone’s upset about DeVos. Or, at least, most of the people I know are. These days, I’m in a new sort of bubble, populated with likeminded people who are not CRC, but who are, I guess, “liberal elites.”

Betsy DeVos is comically terrible. When asked about whether guns should be allowed in schools, she answered, Palinesque, that teachers and principals needed to guard students from grizzlies. When asked about laws meant to protect students with disabilities, she appeared ill informed. When asked whether she supported “equal accountability for all schools that receive federal funding,” she eventually answered that she did not. With her millions of dollars of contributions to the GOP and to the senators who would confirm her, she seems to be yet another aristocrat in our blooming oligarchy: all morals and money, no sense. Why is she, a person who has never set foot in public schools, so keen to destroy them?

Perhaps DeVos was taught, like I was, by some of her elders that the public schools were an evil, full of vice and secularism, with poor reasoning and bad morals, and teachers who, because unionized, cared only about their paycheques and pensions and not about their students. Perhaps she really believes this to be true. Perhaps DeVos is like the students I had, briefly, when I taught in a Christian University, who had many things to say about atheists, and what they believed and how hopeless they were, and how wrong. I asked my students: “Do you know any atheists?”

The answer was no.

*

A recent Mother Jones article made DeVos’s milieu in Holland, Michigan, out to be a place of extremely pious isolation: “They wanted to keep American influences away from their orthodox community. Until recently, Holland restaurants couldn't sell alcohol on Sundays." While Calvin communities might seem to outsiders like a place for homogeneity, a place fearful of “dangerous” ideas about evolution, maybe, or sexuality and gender, it is not anti-intellectual the way many Christian settings are assumed to be. Yes, my mother’s rules for Sunday behavior growing up were strict, and even as a child in the ‘80s and ‘90s I wasn’t allowed to shop on Sundays or take the Lord’s name in vain, but Calvin in the ‘60s and ‘70s was not a place untouched by American culture. While my mother was at Calvin, she participated in a fast for the victims at the Kent State Massacre, and she and many of her fellow students were engaged in discussions about and actions in solidarity with the civil rights and women’s movements. She was the daughter of a milkman and a homemaker, and Calvin College expanded her world: “My life was changed by a handful of professors who had faith with intelligence, imagination, grace, and subtlety,” she says.

When, as a kid, I told people that I went to a private Christian school, they always thought they knew what I meant, and they were always wrong. The subculture that was my whole world for 18 years was more intensely religious than the publicly funded Catholic schools were, but was also unlike the even more sheltering evangelical schools you hear so much about. We prayed several times a day, and we memorized Bible verses, but we did not fear novels, even those featuring witches and wizards. Like the Puritans, we only wanted the right to practice our religion in our own way, to educate our children in the faith we understood to be the best of all possible worldviews. Our campaigns were not evangelical but educational.

When I was a high-school student demanding that my mother tell me why the Big Bang wasn’t a good explanation for where we came from, or why abortion was wrong, she told me about her Calvin professors who had taught her to be open to scientific explanations of creation. She offered poetic descriptions of the case for pro-life, which had to do with our knittedness-together in the womb by a loving God, a God who told us in the book of Jeremiah, I know the plans I have for you. These poetic answers were always a consolation to me, even though they never actually answered my questions. Throughout my peculiar Christian education I was taught, relentlessly, that it was good to grapple with difficult questions and to dwell, often, in a place somewhere between one side and another, always arguing and thinking and asking and making art and praying and feeling humbled by how little we knew.

*

There is some trouble when translating attitudes of grappling and openness and ambiguity to politics, a realm for certainty and action. Before DeVos was confirmed as Education Secretary, representatives were barraged with phone calls. We of the Women’s March took it on as an important next action to oppose her confirmation. People were distraught by her lack of experience and her apparent lack of interest in preserving the public school system. We laughed at and we lamented her stupidity, as we had once laughed at and lamented Sarah Palin and George W. Bush.

I know DeVos is wrong, but I do not want to outright reject her. I want to educate her. Because of her proximity to me, because of our shared community, because she is the only Dutch Reformed person to have reached such prominence, I have trouble dismissing her. But I can see that this sympathy for her teeters closely to the edge of the thing we are all now facing: that people voted for the person they thought seemed most like them, that they voted tribally, primally, many of them without thinking compassionately or well.

The DeVos family believes “patriotism and politics are inseparable from Christianity.” Many people believe this: that religion is determinate of the political right in America. But we weigh religious belief too heavily when we consider what shapes a person. We tend to see religious outlook as different in kind from other parts of our identities, such as political affiliation and wealth. These, with patriotism, are far more influential factors here.

That DeVos is from Holland, Michigan, home of “windmills and tulips, wooden shoes, and signs that read ‘Welkom Vrienden,'" that she went to Calvin College and was raised CRC, tells us less than it seems. All sorts of people come out of these schools and churches; some become conservative Christians like DeVos, some lose their faith, many others are lefty believers. Recently, over 700 alumni of multiple generations of Calvin College signed a letter stating that they did not believe Betsy DeVos is qualified for her position. As Abram Van Engen writes, “religious traditions can be highly formative without yielding predictable results.”

*

After I left the CRC bubble for the wider world, I, who had never known any unbelievers, was suddenly in love with one. I had an epiphany one day as I sat in a movie theater, which now seems paltry but then seemed deep, because I had never felt the force of it before: these were all just other people. I was not set apart; I was not special. We were—and we are—all in this pit together. To listen to those who are unlike ourselves might provide a necessary corrective of humility and uncertainty to our politics, which is called for given the heterogeneity—not a mere two-sidedness—of our population. I want to think my problem regarding DeVos is productive, but I am no better at listening to her because of it. She certainly won’t be listening to me or to countless others who are disturbed by her record. It’s hard to be optimistic right now, about politics or religion, about the possiblity for conversation, but I’m sitting here, as always, in that sliver of overlap between outright terror and foolish hope.