Be the change you want to see in the world. You can judge a society by the way it treats its animals. The good man is friend to all things. The worst form of violence is poverty. “What do you think of modern civilization, Mr. Gandhi?” “I think it would be a wonderful idea.”

If the Internet is to be believed, Gandhi was a brown Oscar Wilde, ready with a moving, perfectly phrased bon mot for every occasion of injustice.

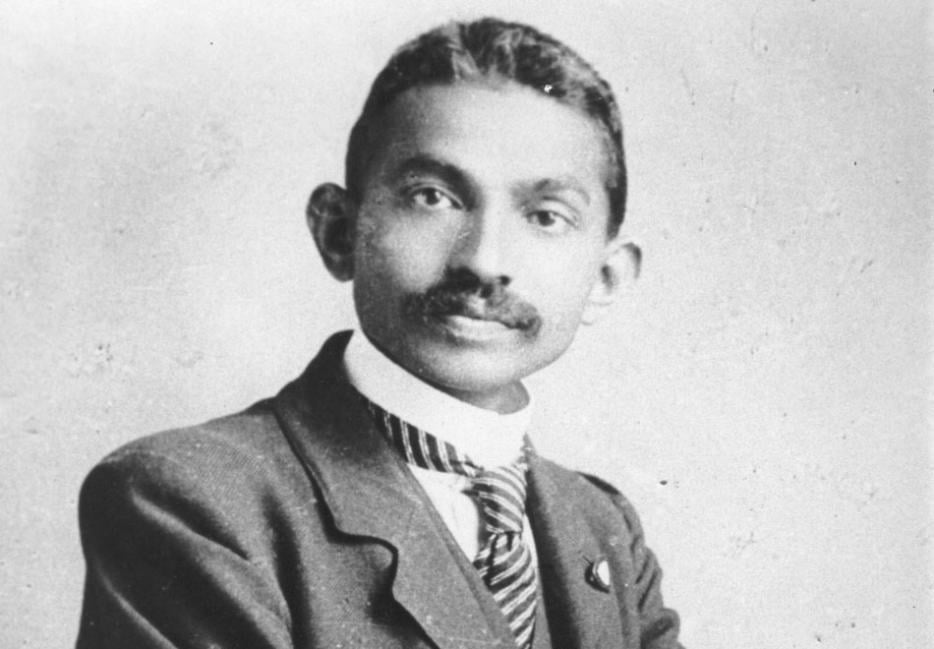

Ramachandra Guha’s new biography, Gandhi Before India, is here to tell us, however, after years of unusually close research that has brought to light many primary documents never before considered in a major work, that there’s a good deal more to Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi—and a good deal less, too.

When I was in Johannesburg recently, I stayed for several weeks a couple of blocks from Mandela’s house as he lay dying in a Pretoria hospital. It finally got me to read his luminous autobiography, the greatest effect of which on me was to make the secular saint back into a human. Mandela wrote about killing people, for instance, and his continual decisions that put his struggle ahead of any responsibilities he might have to his wife an children. I finished the book admiring the work more, the man less, and with a greater understanding of the relationship between the two.

I had read Gandhi’s Autobiography a couple of decades earlier, after seeing Richard Attenborough’s hagio-pic. It left me staggered, in awe of a man who was not like other men, a man who was able to achieve massive change in the world by what appeared to be nearly miraculous—and at the very least heroic—means. Despite its subtitle, The Story of My Experiments with Truth, Gandhi’s book was about a man who actually seemed to have found it.

There’s some value in sitting at the feet of gurus, absorbing wisdom like young sponges, believing that at least someone has it figured out. Now, I’m not sure if Gandhi ever did have it figured out, but the great value of the first volume of Gandhi Before India (the second will be published next year) is that it proves with great detail and no little relish that he didn’t always.

“The Parliament has not yet of its own accord done a single good thing,” he wrote in 1909, the year he turned 40, about the British government, “hence I have compared to it a sterile woman.” Put that on a poster. In the same book, Hind Swaraj (or Indian Home Rule), he denounced modern hospitals, saying that if they weren’t there to treat venereal diseases, there would be “less sexual vice amongst us.” And these weren’t just words: when his wife’s life was threatened by internal hemorrhaging, he took her out of her doctor’s care and, following the principles of hydrotherapy he followed, soaked her in a bath instead. She lived, but one suspects it had little to do with M.K.’s looney-tunes treatment.

Gandhi moved to South Africa to be a lawyer when he was 24, and Guha collects 15 years of quotations and references to his continual denigration of the black Africans he lived among, only calling them Africans for the first time in about 1908. Before that, they were kaffirs. Like Smuts and the other colonialists, Gandhi thought they were incapable of anything so sophisticated as passive resistance. This was not just a case of a 19th-century man expressing 19th-century prejudices: this was a man who had devoted his life to fighting racial prejudice consciously deciding that, unlike the Chinese, with whom he worked closely in South Africa, black Africans were indeed inferior—well after others in South Africa, England and North America had already left this sort of thinking far behind.

When his wife’s life was threatened by internal hemorrhaging, he took her out of her doctor’s care and, following the principles of hydrotherapy he followed, soaked her in a bath instead. She lived, but one suspects it had little to do with M.K.’s looney-tunes treatment.

Gandhi was also, it turns out, what sounded like an insufferable, self-righteous prude. After making a vow of celibacy (about which he famously did not consult his wife), he began to see sexuality as brutish, warning his adult sons away from not just physical intimacy, but marriage itself. During one of his stints in prison, he said he was made “extremely uneasy” by an African and a Chinese man when they “exchanged obscene jokes, uncovering each other’s genitals.” Oh dear me, how dreadful.

Quite contrary to what one might have suspected his views would be on forgiveness and the perfectability of the human spirit, he wrote in anger in the newspaper he edited—well after he’d come to his enlightened stance on passive resistance—about an activist who decided he’d had enough and gave in to authority, that “a bad coin is always a bad coin.” In the same paper, produced on a farm just outside Johannesburg, he took to naming and shaming any Indian who did not join him in his resistance to discriminatory laws.

He was, in other words, a bastard. And I’m delighted by the fact, in the same way I was after reading Mandela’s book: it’s good to know actual humans with familiar character defects can do the sorts of things those two men did.

But uncovering the jerk Mahatma is only a secondary pleasure of this engrossing book, which is, primarily, a revelation of the significance of Gandhi’s years in South Africa in all its particulars. It makes a strong case that, had he not spent as much time as he did there, what he did later in India would have been impossible.

Indians in India were comparatively well treated by their British masters, who undoubtedly had a sense that it might be wise not to prick a population of 300 million too hard. The years Gandhi spent in London, studying law, were similarly kind to him, though a bit of a shock to me: I imagined the sort of racial tolerance we see today in places like Toronto to be quite a new thing, at least in the modern world. But England elected its first Indian MP in 1892, and its second just a few years later. Queen Victoria had a tutor named Abdul Kamir who taught her Urdu. Gandhi had no particular problems being an Indian in 19th-century London—he even found a number of vegetarian restaurants.

It was only when he went to South Africa to practice in 1893 that he encountered open prejudice. His being thrown off a train in Pietermartizburg for refusing to vacate his first-class cabin was made famous by the Attenborough film, and the biography on which it was largely based, where it was presented as his Pauline moment. But Guha makes a good case that, though he was appalled by his treatment, since it was just one man treating another poorly, it did not actually have a great effect on him. What did have an effect, he maintains with some credibility, was getting beaten by a mob in Durban three years later.

He was, in other words, a bastard. And I’m delighted by the fact, in the same way I was after reading Mandela’s book: it’s good to know actual humans with familiar character defects can do the sorts of things those two men did.

A ship carrying Gandhi, a lawyer friend of his named Laughton, and a great many Indians had just landed in Durban from India. Worried about the “Asiatic invasion” taking their jobs, their land, and their culture, 5,000 white Durbanites gathered at the docks in a harbour known as the Point to let them know they were not wanted. It was 1896, and Gandhi was already known, so he and his friend stayed onboard, hoping the mob would disperse. When most of them had, the two of them got on their tender and went ashore:

“As their boat was landing, some white boys loitering about recognized the Indian barrister. They sent word to the remnants of the retreating crowd, who hurried back to the Point. Laughton and Gandhi hailed a rickshaw and were about to step into it, when the boys laid hold of the wheels. The barristers tried to get into another rickshaw but, sensing the mood, the driver was unwilling to take them. Gandhi and Laughton decided to walk on with their luggage. From the Victoria Embankment they walked northwards on Stranger Street with a crowd of ever greater numbers following them, hissing and jeering. Then they took a turn towards West Street. When they neared the Ship’s Hotel—as its name suggests, a place favoured by seamen—Gandhi and Laughton were surrounded, and the former set upon. The Indian became ‘the object of kicks and cuffs, [according to a report by the Natal Mercury], while mud and stale fish were thrown at him. One person also produced a riding-whip, and have him a stroke, while another plucked away at his peculiar hat.’”

It was after this scuffle, Guha contends, that Gandhi saw the true nature of racial prejudice, at least as it pertained to Indians. Thereafter, he saw through the condescending niceties to which he’d been unwittingly subjected in India and London, right down to their unvarnished substrate, and devoted himself to undermining it.

Guha also quotes Henry Polak, a South African friend of his, and one of many Jews who figure largely in these early struggles, writing to Gandhi during a tour of India to raise funds for their South African efforts:

“Everybody to whom I have spoken, Hindu, Mahomedan and Parsi alike, feels that we are far advanced politically over the majority of Indians here. They all feel we have sent a lesson which they ought to follow but that they will have the greatest possible difficulty in following.”

Indians in India were, as Gandhi had been, under the impression that India was part of an empire, and that they therefore enjoyed the rights and privileges of being citizens of its economic engine. But South Africa then was much like it was in Mandela’s time; the occasional liberal white man, even when he was in a position of power, couldn’t do much to stanch the flow of racial fear and hatred. South Africa gave Gandhi the blacks and whites he needed to spur him to action, and the blatancy of the racist opposition won him fans and support in India and England, support that grew large enough to ultimately propel him across the Indian Ocean to take the fight home.

Guha’s epigraph quotes from Gandhi’s Autobiography:

“I understand more clearly today what I read long ago about the inadequacy of autobiography as history. I know that I do not set down in this story all that I remember. Who can say how much I must give and how much omit in the interests of truth? … If some busybody were to cross-examine me on the chapters already written, he could probably shed much more light on them, and if it were a hostile critic’s cross-examination, he might even flatter himself for having shown up the ‘hollowness of many of my pretensions’.”

The author is most certainly a busybody, and though he’s not at all hostile—he doesn't much judge Gandhi for his racism and his sexism, nor his ridiculous medical beliefs—this is most definitely the cross-examination Gandhi had in mind.