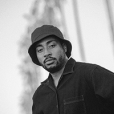

Remembering Phife Dawg’s legacy in the face of his death at age 45 this morning, I’m brought back to one of his most-quoted lyrics: “Float like gravity.” It doesn’t make scientific sense, but it’s rapped with such conviction that it’s cycled around my head for decades. Absurdity was a tool wielded regularly by Phife Dawg in his work as a member of A Tribe Called Quest. Who would fear a “five foot assassin?” Phife proudly liked his beats “hard like two day old shit.” On “Vibes And Stuff,” Phife let loose his manifesto: “All I do is write rhymes, eat, drink, shit and bone.”

While Q-Tip was inclined towards creative techniques like wordplay and extended metaphor, Phife was significantly more down-to-earth. Neither of them had latched onto the stylistic revolution that Rakim’s multisyllabic rhymes wrought upon the hip-hop landscape in the ‘80s. Other New York rap groups like Public Enemy, Ultramagnetic MCs and Big Daddy Kane were ripping tracks at hyperspeed by 1990, but Phife was still intent on rapping with a plodding, raw confessional style that focused on relatability.

If Q-Tip was the emotional and spiritual compass of the group, Phife was the base that rooted them to their home in Jamaica, Queens. He was the voice of the streets that would pull Tip back whenever he veered too far away from where they came from. Phife rapped exclusively about terrestrial concerns. His style was black barbershop shit talk rhymed to the beat, a verbal sports news ticker referencing a broad spectrum of athletes including Bo Jackson, Buster Douglas, Scott Skiles and Vinny Testaverde. He opens up a song by giving a shout out to his “best friend Steven at the Home Depot.”

1990’s People's Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm was remarkable for the group’s fresh perspective and jazzy positive rhymes but if it wasn’t for Phife’s contributions, Tribe could’ve easily been lumped in with their fellow Native Tongues in groups such as Black Sheep and Jungle Brothers. Phife’s verse on “Can I Kick It” showed off the streetwise edge and unpretentious manner that would save A Tribe Called Quest from being perceived as just those weird guys that made “I Left My Wallet In El Segundo.” His impact is so memorable that it seems unbelievable that he’s only featured on four tracks on the album.

But he said a lot with a little. His verse on The Low End Theory’s “Jazz (We’ve Got)” boasts of Tribe making “strictly hardcore tracks, not a new jack swing,” eschewing the crossover potential of the R&B trend of the moment and positioning themselves opposed to it. “I sing and chat, I do all of that,” he spits later in the verse, adding heavy emphasis on the word all, as if to explain that rapping and talking are two very different skills.

One of his greatest moments is Midnight Marauders’s solo track “8 Million Stories,” a song where Phife flips the conceit of Ice Cube’s 1993 track “It Was A Good Day” by rapping about a totally miserable evening in New York. What Phife chose to include in his story is indicative of his everyman persona. His “blood pressure’s blowing up” about not being able to find a Barney doll for his little brother. He’s “stressed out more than anyone could ever be” about having to clear the samples for the Tribe album you’re listening to (why is this his responsibility?). He gets tickets to the Knicks game but shooting guard John Starks is ejected. Story rap was typically focused on fantastical tales or street parables but the mundane annoyances of “8 Million Stories” are distinctly New York in a way that recalls both Spike Lee and Larry David.

Something that can be easily lost in A Tribe Called Quest’s funky grooves and playful nature is the subtle social conscience that represents a continuous thread throughout their discography. Q-Tip was more likely to approach things on a macro level, dissecting the use of the word “nigga” in the black community, delicately representing several perspectives on this issue over the span of an entire song (“Sucka Nigga”). Phife dealt with things on the micro level, coming off as a well-liked guy in the neighborhood asking a question at a town hall meeting. On “We Can Get Down,” he perfectly described the way hip hop culture has frequently been derided as negative by establishment figures who have failed to realize the variety of viewpoints espoused by rappers: “How can a reverend preach when a rev can't define / The music of our youth from 1979 / We rap by what we see, meaning reality / From people busting caps and like Mandela being free.”

Phife died from complications due to diabetes, and his battle with the illness was well-publicized. In Michael Rapaport’s 2011 fly-on-the-wall Tribe documentary Beats, Rhymes & Life, Phife says of his struggle, “It's really a sickness. Like straight-up drugs. I'm just addicted to sugar.” That a person who once playfully rapped, “Drink a lot of soda so they call me Dr. Pepper” might be undone at such a young age by this disease feels so unfair. My uncle plays saxophone and leads a funk band, and he’s also a diabetic. This condition that has brought him so much pain throughout his life was made just a little bit easier because of Phife’s ability to rap about it. How do I know? I’ve heard my uncle proudly refer to himself as a funky diabetic on more than one occasion.