We can forgive America for its collective double-take when Secretary of State John Kerry, speaking in early September, said that any airstrike on Syria would be “unbelievably small.” Surely he didn’t mean it literally, that an attack could be so tiny as to be unavailable to the human imagination, but then what did he mean? Political opposition in Congress and on Fox News went, if we follow Kerry’s lead on military euphemism and hyperbole, ballistic. They accused the White House of threatening Assad and his chemical arsenal with mere “pinpricks,” and this time they had the Secretary’s own words to back it up.

So Obama went on TV to set the record straight: “the United States military doesn’t do pinpricks,” he declared, a sentiment that by now has gone straight to T-shirt. But all this leaves the Pentagon in the lurch. They might well be asking: just what kind of war do these gentlemen want? Bigger than a pinprick, but smaller (though not unbelievably smaller) than the firebombing of Dresden in 1945? This leaves a lot of wiggle room.

Maybe it matters that John Kerry is a war veteran. Compared to what he saw in Vietnam, the kind of GPS-guided Tomahawk missile attacks that have been road-tested in Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Iraq may seem a marvel in efficiency. A Tomahawk missile carries a 1,000-pound warhead capable of destroying a two-story house or leaving a 20-foot diameter crater on open ground. It finds its target 85 percent of the time. Compared to a dump of napalm that may, to Kerry, seem small, insofar as the “footprint” is contained.

The thing about military technology is that it’s forever getting better, in the eyes of those that wield it, compared to the last war, and there’s always a last war. Even in 1945, the bombing of Dresden was seen as a fairly precise bit of business against the relative mayhem of World War I. This, too, is the madness of war: men who convince themselves and others that this time they’re doing it better, even more humanely. History is clogged with such moments.

This is what the Swedish writer Sven Lindqvist tells us in his ambitious, peculiar, and abrasive book A History of Bombing which, at 186 pages (plus notes), is unbelievably small given its title—although its promise of “A” history of bombing, and not “The” history, is crucial. It is a frustrating book. It can be read as a chronology from front to back, but the author encourages a kind of hypertextual skipping-around between numbered paragraphs: item 4 on page 1 sends you to item 93 on page 39, and so on.

I can think of few things less appealing than the games authors play to freshen up the craft, but then I can also think of few things less appealing than being lectured by a smart Swede on the history of bombing in a conventional narrative. Lindqvist’s format works because it forces you to contend with the messiness of history rather than pretending it all makes sense (and it matters that he wrote it in 2000, before online hypertextual skipping-around became as natural as breathing.)

Early in A History of Bombing we learn that soon after man learned to fly, he learned how to drop things—explosive things—from airplanes. Kitty Hawk and the first manned flight was in 1903, and the first bomb dropped in anger exploded near Tripoli only eight years later. In the colonial war waged by Italy against Libya, the Italians were able to test-drive the new technology: small, round bombs weighing a kilo-and-a-half each, dropped by hand from a Fairman biplane. This was deemed by international law to be just and right.

Lindqvist sends the reader on a complex narrative chase through a history of colonial war in which a common theme emerges: the Western powers agreed that in order to bring civilization to “barbarians and savages,” some blood had to be spilled. Better to control this mission from the air, where some measure of containment is assured, than to leave it to the blind chaos of armies and artillery. Airstrikes, from the beginning, were seen as more humane.

Lindqvist recalls a poem from his childhood, Bo Bergman’s Holy War:

We blow it to bits. We civilize with explosions.

Here lie the civilized, in long, quiet rows.

Then came the rest of the 20th century, in which the architects of air warfare no longer bothered themselves with moral delusion: from Guernica in the Spanish Civil War, through World War II, Korea, and Vietnam, the idea of “fronts” defended by armies dissolved in favour of slamming every inch of enemy territory. By the late 1920s, writes Lindqvist, the military experts had already framed the idea of sparing civilians as “absurd and antiquated... quite simply a function of the artillery’s limited range. Now that flight had extended that range enormously, there was no reason to limit warfare to those who could defend themselves.”

The Geneva Convention of 1864, which held that “the unarmed citizen is to be spared in person, property, and honour as much as the exigencies of war will admit,” still held, but that last clause made for a handy loophole: clerks and factory workers in Guernica who were not spared by Luftwaffe bombs became, according to international law, quarry to the “exigencies of war,” or what we all later came to call collateral damage. Same goes for North Vietnamese farmers, who, decades later, had the bad luck of plowing within napalm range. Syrian bus drivers, you’re next.

Step by step, hopping from the nuclear cold war to the 19th century conventions on global law, Lindqvist lays down the faint chalkings of a pattern: every war is a fresh start, and those who wage it are able to reinvent the debates over what’s acceptable and what isn’t based on what happened last time. Reading A History of Bombing with Syria in mind, it’s possible to see the evolution of self-justification: we must bomb Damascus to save the people from their own savage leadership (the colonial impulse), but not so much that we threaten the unarmed (technology permits something along the lines of limited destruction). As always, military action is framed by the loose “exigencies” otherwise known as shit happens.

The issue for the rest of us, if we’re up to it, is not to be flattered by the rhetoric which says: we’ll really do it better, safer, quicker, unbelievably smaller this time. “The injustice we defend,” writes Lindqvist, “forces us to hold onto genocidal weapons, with which our fantasies can be realized whenever we like. Global violence is the hard core of our existence.” Change starts with admitting it.

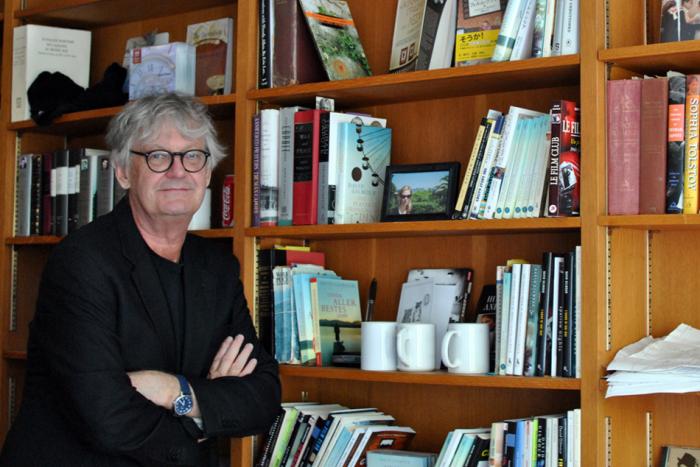

The Lost Library: forgotten and overlooked books, films and cultural relics from Tom Jokinen’s overstuffed Ikea bookshelves.