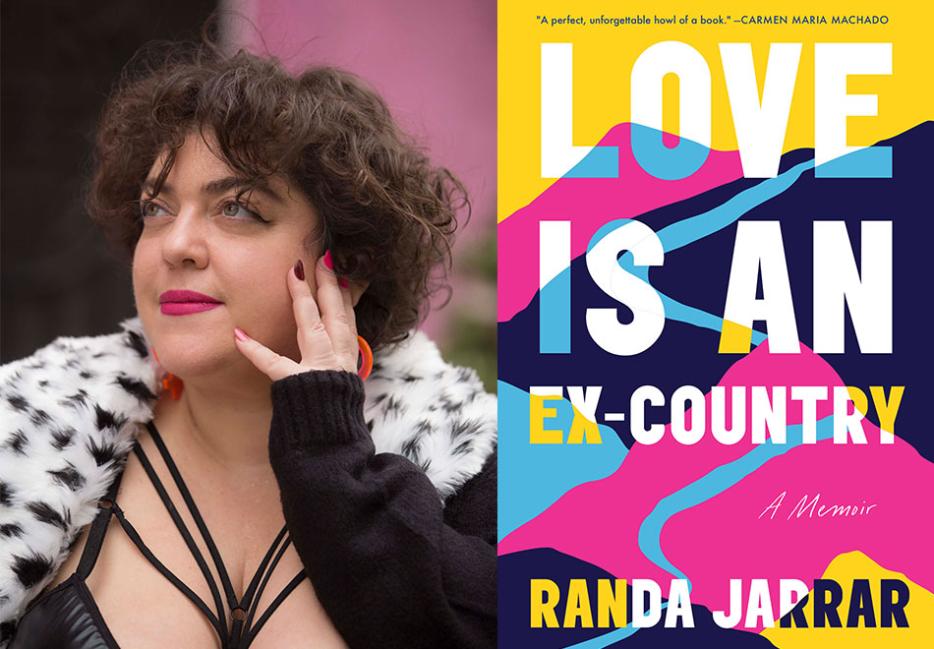

Randa Jarrar says what’s on her mind. In 2018, after the death of Barbara Bush, she made national headlines after sharing a tweet that opposed the veneration of the former first lady. Jarrar found herself in the midst of a free-speech controversy. Her safety and her family’s safety were put at risk by the doxxing of her home address and personal phone number. She received death threats from white nationalists. Even her employment at Fresno State became threatened. Although the experience was painful, it stands as an example of Jarrar’s strength to boldly speak the truth.

Born to an Egyptian mother and a Palestinian father, Jarrar’s identity has always played a significant role in her work. In her first novel, A Map of Home, a coming-of-age story set in Kuwait, Egypt, and Texas during the 1990 Palestinian-Israeli conflict, Jarrar captures the struggles her own family faced. Her second book, a collection of short stories called Him, Me, Muhammad Ali, explores the lives of Muslim communities.

With Love Is An Ex-Country (Catapult), Jarrar returns with a road-trip memoir. In 2016, largely inspired by the Egyptian dancer and actress Tahia Carioca, Jarrar journeyed across the United States. She began in California, where she currently resides, and ended at her parents’ home in Connecticut. Her memoir is not a typical, linear travelogue. She meanders, not only narrating the road trip itself, but the moments in her life that brought her there.

I spoke to Jarrar about the importance of Tahia Carioca’s story, reclaiming joy, and the meaning of place.

Sabrina Papas: The road trip you took was inspired by the Egyptian dancer and actress Tahia Carioca. Can you tell me about what drew you to her story?

Randa Jarrar: I just really love iconic women who flout whatever ideas people have about what they should be doing with their lives. I’ve always been fascinated with artistic women in Egypt and Palestine—which is where my parents are from—and the fact that they were doing whatever they wanted in the ’40s when most people in the Global South were not doing whatever they wanted, at all. The way that they used their art to kind of drop out of what their societies expected of them—that to me is really fascinating.

And so, for Tahia Carioca to decide to become a belly dancer, be really good at it, and then be promiscuous or very sex-positive, embracing her desires—she was a woman who really just embraced her desires, and went for having lovers when she wanted to. And she ended up marrying them, obviously. The idea of her crossing America twice, back and forth, in the ’40s, was fascinating to me. [This was] right after World War II, with some guy she met in a Cairo bar when she was dancing. I could relate to it, but I also just felt like I could learn from her and the way she moved, literally and figuratively, in the world.

I had never heard of her before and I looked her up and watched some videos, there’s something about watching her move—it’s so beautiful and captivating.

It is. I wanted the book to be about bodies and about the ways that bodies are able to move and celebrate and be celebrated. I’d known of her since I was a kid. There were all these amazing black and white Egyptian movies on TV growing up, and she was always the most fascinating because she just had a weird name and danced in this way that made me feel things. And I was a queer child and I didn’t really know what those things were. That’s really what drew me to the story. I was already drawn to her from a young age.

When Carioca died in 1999, The New York Times published an article in which they wrote that she was “often called the Marilyn Monroe of the Arab world.” What are your thoughts on the reductive need to define a white counterpart for a person of colour, rather than allowing them to be their own person?

That’s awful. I think it’s just the way that the Global North tries to translate, for a Global North readership, the experiences of people of colour. To me, that’s not an accurate translation though. Marilyn Monroe was an okay dancer. Marilyn Monroe wouldn’t even be exciting to me as a porn star. [I’m] imagining how amazing porn stars are versus Marilyn Monroe. People call her curvy but she’s just very plain, in my opinion, compared to Tahia Carioca and women of colour in general. It’s just their way to translate and they don’t realize that they’re insulting. Or maybe they do, but it doesn’t matter cause the harm is already done. She’s so much hotter than Marilyn Monroe. She also survived. She lived until she was an elderly woman and kept working. So there was a strength there that Marilyn Monroe lacked.

You undertook your road trip in 2016. In Love Is An Ex-Country you write, “I wanted to commune with the land I lived on, to see America during that deeply troubled and troubling election year. To look at the place that might elect a person like Trump.” By the end of your journey, did you find any comfort in forming your own connection with the land?

I don’t know if I felt a comfort. In the past, I’ve always tried to find replicas of the places where my ancestors are from. I think crossing the country made me realize that this area, Turtle Island, it’s not a replica—it’s its own magical, unique place that doesn’t belong to us, that belongs to the Indigenous people of the land. It really made me feel more aware of myself as a settler, asking myself questions like, “Are diasporic people capable of settling?” “Are people who have been pushed out capable of settling?” It made me question more the ways that I was reducing this country to a replica when it was its own majestic place that had also been made into replicas by Westerners who came and colonized and settled it.

In a way, it took the mask off and made me really aware of what this place is and how much of it is abandoned. There’s so much I was driving through where there was nothing. It didn’t seem like there was a lot going on. In those spaces, I felt like I could really see what it could have been if it hadn’t been damaged and settled on. I feel like that’s what I mostly learned on that trip. And it’s very vast. It’s definitely a lie to say that America is this one unified place—it’s not. It’s so many smaller communities and places.

There’s a chapter in your book about the backlash you received when, following Barbara Bush’s death in 2018, you shared a tweet calling her a racist. The tweet brought on a lot of online abuse from the alt-right, and even threatened your tenured position at Fresno State. Since then, have you felt a need to limit what you say on the internet?

I think what you’re referring to is chilling my speech. It didn’t make me watch what I say more on the internet; it made me more aware of security concerns. I think a lot of people who get doxxed, a lot of them [aren’t] aware that so much of their information is out there. The fact that they could find my family members, my phone number, my house address—I realized that I had a responsibility to the people that I loved. If I did want to say whatever I wanted, I needed to think ahead of time to protect them. Now that I’ve taken those steps, I can continue to say whatever the fuck I want.

I think we’ve also seen a shift in the last couple of years. There’s so much being said on Twitter so openly. That’s really helped. People like me, I think we serve as catalysts to get the culture moving forward, and then we get attacked. But it’s just to move the culture forward in becoming more comfortable telling the truth and labelling things what they actually are. People, since then, have talked so much shit about people who have died. Sometimes when you’re before your time, or ahead of your time, you suffer for it. I’m happily just saying whatever I want still.

Despite the response you received, you write that you felt that you had still won. Alt-right publications were repeating what you had written over and over again. They may not have agreed with you, but they were inadvertently aiding you in getting out your opinion. Are there certain concessions that you have to make in order to be heard?

I wonder if I think about it as a concession. It wasn’t just [the] alt-right, it was just generally the news repeating. Those magazines were trying to attack me as a person, but they were still repeating my message. I think that if you’re a woman in the world—if you’re a fat woman, a woman of colour, even someone like me who’s very light skinned and has that privilege, if you’re openly and proudly Muslim, or some other kind of marginalized identity, and a combination of identities—it’s not really concessions. But you have to be aware that you will be attacked on those kinds of superficial/identity markers because you’re not supposed to be talking. You’re not even supposed to exist, actually, let alone talk or speak. I think all of us are, or have to, be aware [that] that’s one of the consequences.

What’s really interesting to me about freedom of speech or the freedom to say what you want, a lot of people will say, “There’s consequences to freedom of speech.” To me, the number one consequence to freedom of speech is [that] the person receiving the speech is uncomfortable—that’s actually the real consequence. People like to say, “Well, the consequence is that you’re gonna get punished for saying it like it is.” No, actually, the consequence is you’re gonna get uncomfortable from hearing someone say something. So [it’s] just realizing and shifting those conversations and those ideas of how speech works and what its “consequences” actually are. They tend to be unfair, as I’ve just said, when you’re a marginalized person.

There are many moments of joy in your book. I think there’s often a sense of guilt, especially in our current moment, when we allow ourselves to really feel joy. How do you reconcile the anger you feel with letting these moments of joy into your life?

For those of us who have dealt with all of this bullshit for so many years, experiencing joy is revolutionary. I’m not the first person who has said this. There’s a lot of pleasure activism out there—the idea that claiming joy in a world that doesn’t want you to be joyful is radical. Claiming rest is radical. My anger is something that can also exist alongside joy. I think for Americans, and people in the Global North, anger is a feeling to be contained, to be displayed in a way that’s non-violent or peaceful. So, often policed. I think it’s really important that we are in a time now when we are saying, “No, fuck the police, fuck all the police.” You can be angry and experience joy.

For me, the guilt that I experienced sometimes during that trip, I realize, is not useful. Feeling guilty for being light skinned is not useful. Fighting hard for a university that I work at to hire women of colour is useful. The action is actually what needs to happen. Joy, anger, all of these are active emotions and active feelings. I just allow it all to just exist and celebrate it, grief, all of that.

In stories of abuse, there’s often a narrative of blame. Usually, it’s wrongly placed on the victim or survivor. You write about the complexities of your relationship with your father. In his old age, you were able to see him as a different person and forgive him. How can we reframe discussions of abuse to avoid placing blame at the forefront?

It can get really tricky, because my own experience as a victim doesn’t have to be a universal one. I think that victims of abuse [each] have their own right to whatever their narrative will be. I’m really interested in ways that restorative justice is being practiced now and the ways that people of colour are looking at ways, outside of police, to get close to that sense of justice. So, I think if someone wants to place blame at the forefront, that’s their right.

Not everyone needs to forgive the person that abused them. I just happen to be lucky enough. My father is literally in pain every day. The first 20 years of my life, I was in pain every day. So, in a lot of ways, I feel like there is justice there. I think, ultimately, he’s also very lucky that I was willing to take those steps to meet him after what happened. I think the fact that he can no longer harm me is also what allowed that to happen. There are so many different variables involved. I think that blame is just a necessary part of the equation. Like you said, it tends to be subverted and falls on the victim, when it’s usually the fault of patriarchy, white supremacy, and the police—all of those together. So really, maybe [we should be] shifting the blame away from individuals and onto a social structure that enables that abuse, that protects violent people, that protects abusers, and leaves victims to their own devices.

I agree. It’s so much more than just the individual in so many cases. It’s difficult to write a person off as “evil,” to villainize people when it’s often a systemic and structural issue.

We know that people are capable of treating people with forgiveness and kindness. Look at the way that murdering white supremacists are forgiven in the press immediately. They’re like, “Oh, this person was mentally ill.”—I’m mentally ill, but I would never harm people—instead of thinking, “Oh, this is a mental illness thing or this is an individual thing,” which only affords those kinds of forgivenesses for, in general, white men or in some cases white mothers like Casey Anthony. Instead of that, focusing on the ways that we can move forward with real justice.

In Chicago you found the apartment building where your parents lived when they first moved to the United States. You also made an attempt to enter Israel in order to see your former childhood home of Palestine. Can you speak about the need to seek out places from your past?

I like to think of time as non-linear. I was just telling a friend that, as a child, I often had this feeling that a benevolent force was looking at me. Not monitoring me, but making sure I was okay. As a young Muslim, I kind of interpreted that as God. God is looking at me; God is making sure I’m okay. Now that I’m older, I’m realizing that there are so many different layers to it. The thing that I was feeling was actually my adult self, looking at my younger self and witnessing what she was going through and coming to get her, basically to say, “Hey, you’re not gonna be stuck in this terrible situation forever.”

For me, looking at those older places, seeing the old dorm room where I think I got pregnant with my child, going to the apartment I lived in before the invasion of Kuwait—all of those times, I felt like I was going back to hold my younger self’s hand and say, “Hey, we don’t have to go through this anymore. Let’s go.” And to also honour that those places are real, and those places are still around. I think that’s something that comes from being a Palestinian. So many Palestinians are denied the right to return. So, for me, it’s giving myself the right to return, wherever it was where I lived, since all of those places in my mind and my heart are Palestine. Even if it’s not inside Palestine, those were the places that I, as a Palestinian, suffered or grew or loved or whatever it is. So, to me, that’s the importance of revisiting. It is also a radical act of self-love and healing.

Do you feel that the tangible existence of the places from your past affirms your existence as well, that they make your past selves feel more real? Do parts of us disappear when we can no longer reach these places?

I was reading yesterday about how many places in San Francisco have been demolished. I had watched The Last Black Man in San Francisco, and I was thinking about Black communities in San Francisco. With the ethnic cleansing, so much of it is connected to literally razing the place and getting rid of it.

I do, I really do think that parts of us [disappear]. I feel like it’s a violation. When parts of your past are bulldozed, or razed, or destroyed, there’s a way that those places aren’t being honoured. What are the places that get to be seen as historical places of importance and receive that kind of reverence? Just the fact that there are fucked up statues everywhere to commemorate people and places where so much pain happened—that exists. But a project where thousands of people grew up no longer exists and can no longer be visited—that’s violence. It’s an act of erasure. It’s a way to bury.

Egypt is a constant building. Everyone always lived around the Nile, so whenever you visit and you go to those places, you’re standing on places that people have lived on for at least 5000 years. That’s what it’s like to live on a land that’s constantly not erasing; it’s adding constant additions, which is so beautiful to me, rather than subtraction, erasure. It’s so hard to just carry things inside you, and not be able to go visit, and not be able to commemorate who you were, who your ancestors were, people who are no longer with us.

It was your father who wanted you to be a novelist. You write that he told you “to write a novel about the history of my family and our struggles.” By presenting your personal history and struggles, do you feel that you’ve achieved this in your own way?

Definitely. My first book [A Map of Home] was fiction. It was a novel about our family. It was a fictionalized version of both my Egyptian and Palestinian selves. So I felt very healed; I felt that I had really accomplished something by writing that first book.

With this memoir, what I’m doing is claiming space instead of feeling like I have to represent so much or do all this stuff for my people. I just took a chance and said, “I just want to commemorate myself and my own body and eradicate any shame I might have around all the different parts of who I am.” That was really important for me with this book. I’ve told everyone in my family not to read it. My line is: “My pussy is in it too much.” Like, “There’s too many pussy appearances, I don’t think it’s for you.” The book is not for everyone and I’m really aware of that, and I’m really into that. I don’t think it has to be.