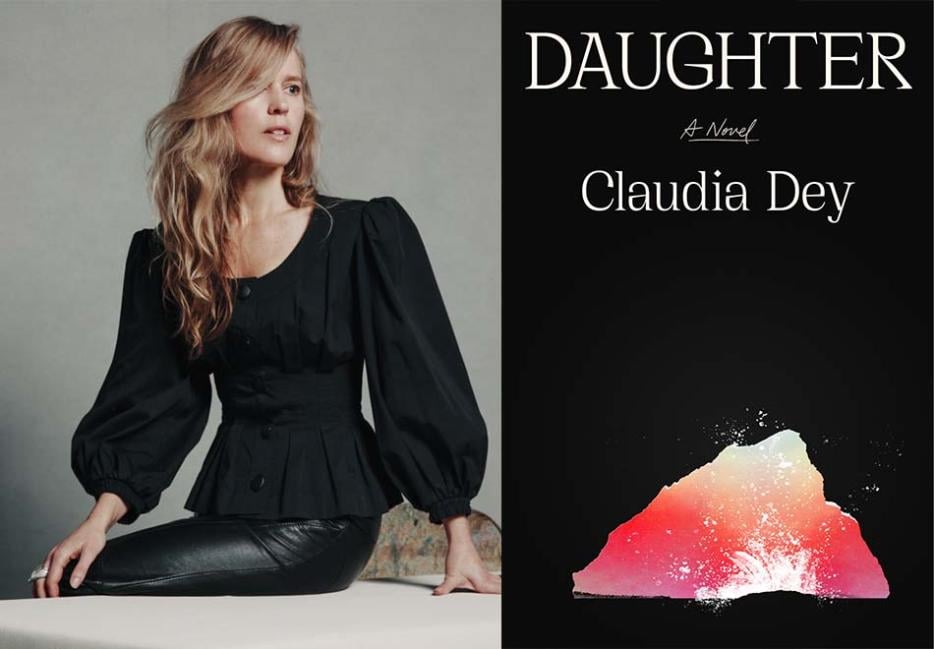

“I do not know who was the parasite, who was the host,” thinks Mona, the protagonist in Claudia Dey’s latest novel, Daughter (Doubleday Canada). Dey’s first two novels, Stunt and Heartbreaker, feature complicated parental relationships. Dey returns to this theme with a larger-than-life father character, Paul Dean, described by CBC as a “magnetic King Lear-esque patriarch.”

In Daughter, we see Mona undergo what Dey described to me as a “revolution within herself.” There is loss, estrangement, grief, and passion on this path, leading her to discover the power and freedom in art. Daughter is an exploration of a toxic father-daughter relationship but also a woman’s relationship with herself. Though Mona has long been stuck inside her father’s world, its sprawling romance and quixotic excitement, she is able, through her own work and self-creation, to find a way out. Even if she is the “daughter” in question in her father’s work of the same name, the word takes on new meaning as Mona moves forward through the narrative. Dey draws perspective inward, removing the lens of the father and freeing the daughter to her own life.

The following discussion about Daughter was had by email one morning in late August. Claudia and I went to our desks at a scheduled time and wrote back and forth, an arrangement she described as “alone but together.”

Fawn Parker: I loved this novel and was thrilled when Hazlitt reached out about this interview. The father-daughter relationship is very present in a lot of my writing and it’s one that I find so rich and fascinating. I think you’ve created a beautiful portrait of longing and grief and envy and isolation. Something that really stuck with me was this idea of grief and forgiveness not being able to be intellectually forced. That they exist somewhere more corporeal. This reminded me of something you said in an interview for the Writers’ Confessions series in Toronto—you compared the writing process to taxidermy, that you feel you’re working with this physical animal, cleaning it and then filling it out. I think you have such a masterful way of holding a character in their physical body despite how intellectual and emotional the writing is.

I also love the way much of the more direct conversation between characters happens through email—Mona and her father and sisters especially—and in person they often seem at a loss for words, or say things they don’t mean. There is such a rich tension in the dinner scenes between Mona and her father. As a reader I felt I had so much insight into Mona’s inner world during some of the silences with others, when she might speak very few words, whereas with the emails I was reading only the plain text. That effect was very cool. This also works well with the format of our conversation this morning. I swear I won’t go any further into the horrible C-virus topic but surely in recent years many of us have considered what is changed when communication happens primarily through a screen. Were you thinking about this in these moments or did this communication style occur naturally?

Claudia Dey: Once I had that corporeality—the characters’ textures, furies, desires, humours, the way they would hold a glass or kick off a shoe or cough or yell—I knew how they would communicate with each other and to themselves. I wrote to achieve the true scale of internal versus external, what is spoken and what is withheld, what is real and what is performed. So yes, the communication style came naturally, but only once I felt I knew my characters in the real and tangible way of living with them. They lived in the rooms of my head.

The emails are, in function and in purpose, meant to communicate, but do they advance or clarify anything for the family? I wrote them as verbal gunfire, as battle scenes, as confessionals wherein the sender’s feeling of rightness in their own position is, ultimately, what is defended. There is no atonement, no resolution other than what can be arrived at independently. Mona and her father’s meetings in his favourite restaurant generate a sense of loneliness just as much as they do love, however uneasy and self-serving that love may be. Their relationship is like a bad romance. The writer, Anna Dostoyevskaya, Dostoevsky’s wife, said the secret to her long and happy marriage was that they never tried to change each other—they did not interfere with each other’s souls. Mona and [her partner] Wes do not interfere with each other’s souls. They allow for privacy in feeling and struggle; they leave the other’s psyche and being intact. You can use this idea of interference as a measurement for the relationships in the novel (and apply it to life if you dare).

I dodged the virus in my answer, but I do think it has completely changed sociability. Perhaps this is why I proposed we write to each other in our nightgowns? Off-screen, and alone but together.

I’m glad you brought up the relationship between Mona and Wes and the way they stay out of each other’s ways. I noticed this right away and appreciated the way they held so much space for each other. This relationship felt so unique to me—in fiction and in life.

That’s a great way of describing the emails, as “verbal gunfire.” Makes sense that we see so much of this in the “bad romance” between Mona and Paul, but more direct communication between her and Wes.

This thinking about internal versus external, spoken versus withheld, real versus performed feels apt for Mona as an actor and a playwright, though of course applies to all characters. Do you feel your characters performing story as actors, or do they feel at times out of your control?

They are out of my control, which is exactly what I want. When they are in my control, the writing is forced—to use your word, performed—I can’t stand it, I can smell the deception.

Annie Ernaux described a writer as a channeller. This is how writing Daughter felt, like channelling. This is the only kind of writing I trust. I am speaking about a first draft—then the craft comes in more consciously and you draft until you have preserved the aliveness of that first draft while achieving the most precise expression of the book. At least, this is the goal. I went for reduction with Daughter. The more sheared a line, the more life it can hold. Like the title.

That’s such a great way of putting it—that the “sheared” line holds more life. I agree with you. I’m excited to have this insight into your process as well as it’s something I’ve felt but not put into words, that the book is only alive in its first draft if you let it be, and the craft comes in at the editorial stage. This element of writing is one that I feel can’t be taught.

I agree that it can’t be taught.

Something else I thought was so expertly handled in a craft sense in Daughter is the manipulation of time. Not only in the non-linear way this story is woven together, but also in the way you employ scene versus summary. Condensing major event into a single sentence or drawing out a singular moment, untangling the richness of the emotion and sensation. I’m recalling the fight between Wes and an old schoolmate, how you introduce it so suddenly and quickly, showing just a glimpse, and then later we get a look inside. Is this, too, something you feel on the level of instinct, or does some of this happen at the editorial stage?

The scenes you’re referring to were written in that first draft—on the level of instinct, as you put it—and in fact, the first draft is intact in the novel; I’ve drafted and built around it and under it, and refined it on a line level for tautness, for heat. Know that I wrote in a very searching way for a couple of years before I found Daughter. It’s a matter of tenacity, persistence. I had a theatre teacher whose advice was, “keep your ass in the chair.” It’s good advice—continue working because eventually the effort will yield into something you trust, something you want to devote yourself to and be obsessed by.

I think so much of art is, at least externally, quite unromantic. It’s just long hours in the chair. But that’s what’s so fascinating about it. You said something about this in an interview about your writing once—I’ve misplaced where—that with writing no one has any idea what you’re doing behind the closed door. This idea you could be washing dishes or sitting perfectly still in silence and no one would know. I think there’s a magic in the finished project in that way—it can feel so sudden and surprising when the writer emerges and the book is complete. Are you fairly private when you’re working on something?

Very private. Totally poker-faced.

Interesting. That’s good I think. Ideas can be so vulnerable, and others’ opinions are easy to come by…

Daughter is a novel of relationships—people defined against or feeling completed or changed by one another. Do you think there is more to identity than how one relates to others? What is that other piece?

I am always intrigued by this emotional math—yes, who we are is mostly who we are in combination with others—divided, subtracted, multiplied—and I wanted the novel to function in this pressurized way—like a black box theatre with a limited number of characters in a limited number of settings, all in relationship to each other. I would say that other piece of one’s identity—separate from the field of others and how they operate upon you—is your relationship to yourself—this sounds obvious, but it is the critical cultivation of that relationship and its expression that makes a person whole and not porous. When we first meet Mona, she is on the ascension path as a writer and a performer. Yet her father, Paul, enters the scene with his urgency and his need and his confusion, and he disrupts her ascension; the bad romance—he loves her briefly then discards her. Mona’s arc is to achieve a revolution within herself—not just in response to her father, but of herself. That is the last identity piece—for Mona, making art is making personhood.

Something she and Paul have in common is how seriously they take not only their work but art itself. In a way writers create a self or at least a version of a self through the bodies of their work. Do you feel any separation between your day-to-day self and your artist-self or are these identities one and the same for you?

What a question. It’s hard to name our multiple selves, but my day-to-day self and my writer self are very much entwined, sharing vital organs. The act of writing keeps my day-to-day self alert—alert to language, to sensation, to everything. It gives the world a shine and an intrigue. I wake up. I kiss my husband, kiss our sons. I make a lot of sandwiches. I go to work. The beauties, the labours. My family is my sociability, and it is very real to me, it is the centre and structure of my life. But then I have this place in my head that is equally real; it is my secret, no one has access. This is where the fictional selves are made. Very Scorpio. I protect it with my life. I can be in conversation with myself, download and sequence all that I have seen and felt. I always have a notebook with me, and have since I was a child. My notebook keeps me sane. I love this Flaubert quote as a further answer, elucidation—I first read it paraphrased by Julianne Moore, “Be regular and orderly in your life, so that you may be violent and original in your work.”

That seems so vital to keeping a writing practice alive, being able to hold it close, keep it secret. I feel the same in the duality of things—the everyday “reality” and the secret mental place. But agree, too, that these two selves are entwined. Reading your answer made me think of second-language learners and the way a person can eventually lose track of what language they are thinking in, or translate so naturally that they speak a mix of both aloud. I imagine this has probably been said so many times before, that writing is a kind of translation. But it’s true.

Early on Mona is remembering a time when she was beginning to write her first play. She claims to have felt “beneath the endeavour” because “[t]here was already a writer in the family and he was a titan.” This is interesting, the idea of there only being space for one artist. Once during some relationship conflict an ex shouted at me, “You think you’re the only writer in the house!” Intimacy between artists can be so fraught, and in this novel it complicates Mona’s self-identity, even when her father is not around. What do you think about the comparative/competitive element of creation/expression?

I’m fascinated by it—by the territorial aspect, by the fear of being surpassed—which is of course, so unparental, so unfatherly. Paul wants to be the only one, the tortured megawatt star, prey to his impulses, alone with his gift, tragically misunderstood by those in his orbit, hoarding fiction like an empire—Wes identifies this during a dinner scene. He sees how Paul praises Mona in a way that is dangerous, in a way that could neutralize her talent. I have a mood board in my study and it is covered with the daughters of famous men. I’m always interested in writing dimensional women who fight for and arrive into agency—women who know themselves, who are not looking to be made legible via the lens of others—I wanted to write a novel with this same agency, an agency that matched its heroine.

Also, I’m glad your ex is an ex.