People who lose a loved one often use the expression “losing a part of myself,” implying that relationships involve a meshing and osmosis. If one’s partner, parent, or family member were to suddenly and inexplicably drop out of their life, how does a person experience it, this double loss of another and a fraction of the self?

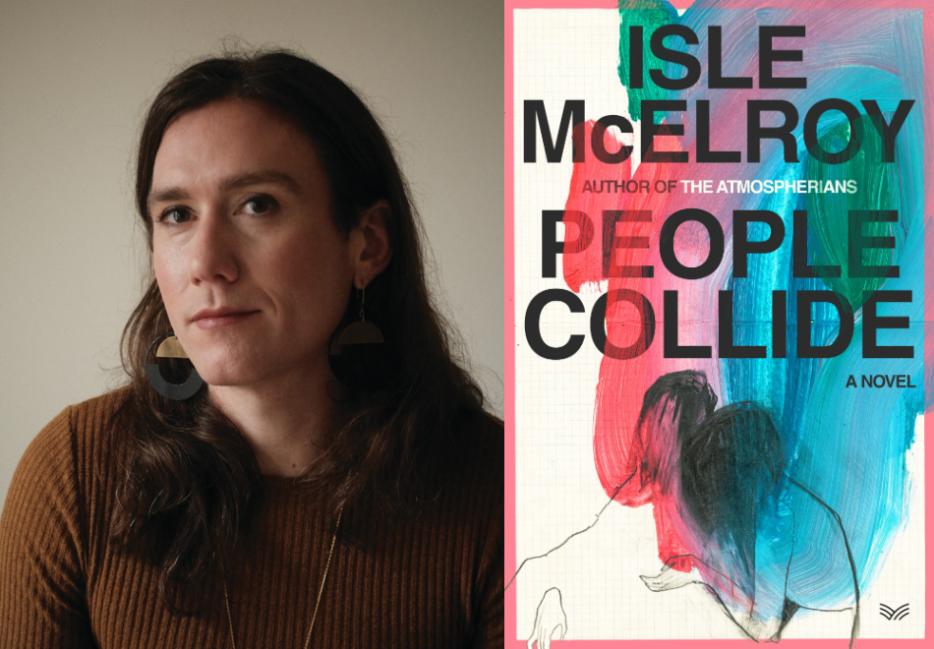

Early in the pages of Isle McElroy’s second novel, People Collide (HarperVia), the main narrator, Elijah, undergoes an event that leaves him “stuck with the fork of disbelief”: a kitten he assumed was dead springs to life and patters away. This is only the beginning. Elijah will soon realize he has undergone a body swap with his wife, Elizabeth—the disbelief that was salad fork–sized has now become a pitchfork, but we’ve been forewarned that the odd is upon us, and we go along for the ride.

McElroy is no stranger to the incredulous and unexpected. Their first novel, The Atmospherians, centres on a cult that rehabilitates toxic men, and its world contains “man hordes”—bands of men who spontaneously group and perform random deeds, good and bad. As with The Atmospherians, People Collide employs surreal, out-there elements in the service of some rather big themes. The body swap of a millennial American couple takes us not into the realm of hijinks, like the body swap TV shows Elijah remembers from his childhood, but is instead a platform for deft explorations of the constraints and malleability of selfhood and gender, inter-spousal power dynamics, and the empathy that can arise when we cross thresholds and literally walk in someone else’s shoes. McElroy skillfully handles it all within the context of “the Incident”—Elijah’s term for the unusual event that’s befallen him.

Getting rid of a part of ourselves is often a goal—its more common names being transformation, betterment, self-improvement. Can ridding oneself of one confining element, such as the physical body, usher in change in other parts that compose the self? And does this change come with a new perspective, and a new host of acts and prejudices others are willing to enact on us? “Each day…is a chance to discard your most pitiable habits and selves,” says Elijah. Can those closest to us be a habit? Is our personality a habit? And so we embark on a strange journey where Elijah’s loss of his partner and of his body provides a chance for him to explore the limits and varieties of selfdom.

I had the luck of having Isle McElroy as a writing teacher in a pandemic-time fiction workshop on narrative openings, and was excited to get back in touch to discuss their new novel and dig into the Incident.

Marta Balcewicz: I’ll start with one of my favourite lines in People Collide. Elijah, finding himself in his wife Elizabeth’s body, says, “I occupied a space where neither she nor I seemed to exist, free from the expectations of our personalities.” I was intrigued by this idea because personalities, unlike more obviously limiting containers such as gender and bodies, are rarely conceptualized as imprisoning. Can you talk a bit more about personality as a source of constriction?

Isle McElroy: I think about it in terms of self-definition or self-knowledge. Personality isn’t necessarily a constriction, in a pejorative sense—at least, it doesn’t have to be—but I do think there are limits to the types of people we can become, how we can act, especially once people get to know us. Elijah faces personality as both a limitation and an aspiration. When it’s the former, he acts like himself when he’s supposed to be Elizabeth; when the latter, he tries to conform to others’ expectations of Elizabeth. Both are constricting insofar as he is either shaped or shaping himself.

There are distinct ways to react to this kind of constriction. Self-knowledge is one option—you can accept your personality as a restriction and learn to love it. I’ve found myself taken aback, in an admiring way, by people who possess loving self-knowledge, who can list what makes them cranky or eager, because I spent a lot of my life ignoring the variations of my personality. Elijah knows very well who he is, and, throughout the book, he comes to see this as a benefit, using his personality to gain advantages Elizabeth might not have, while also benefiting from her personality. In the book, it appears restricting but tends, instead, to be exploitable—because it’s assumed to restrict.

Staying on the topic of confinement, so much in People Collide is about those containers that hold the self: our physical bodies, gender, and, as mentioned before, our personalities. They can inform the self, but none of them conclusively define the self. These topics feel huge, and yet People Collide navigates the question of how the self exists and adapts in the world in a way that doesn’t feel saddled or heavy. How do you think fiction involving a surreal plot element aids a writer in the exploration of—capital b and t—Big Topics?

I think surrealism can take some of the intensity out of subjects that might seem massive. To confront things like gender, confinement, and selfhood head-on, in a realist novel, might result in prose that is weighed down by the subjects, by the literal nature of the engagement, and thus leave the reader with very little space to enter the text. That’s how I feel, at least. And I know that I most often think best through metaphor. Surrealism creates a metaphor the size of the book, allowing for space where the reader may interpret meaning rather than being told what something means. I don’t want to make it appear like this is objectively better, though. Lots of great books confront the abstractions you noted head-on. But I’m simply not that kind of writer, and I like to use surrealism and metaphor as a way to open up the world. My hope is that, as a reader engages with the reality of the book—the body swap—they will also confront the thematic abstractions you noted without feeling lectured. I like when ideas are fun.

Early on in the novel, Elijah makes reference to the genre of “TV shows and movies where people swap bodies.” (I couldn’t help but notice that the swap in People Collide takes place on a Friday—a Freaky Friday?) Elijah references a particular TV show he saw as a child, where a male character’s first impulse upon being swapped into a woman’s body is to run to a bathroom and ogle her (now his) breasts, an action Elijah finds “puerile and predictable.”

Did you come to the idea for People Collide’s plot as a fan of the admittedly vast and long-standing genre of body and/or identity swapping, and what twists did you want to put on it?

Oddly enough, I’m not a massive fan of the body swap genre. I didn’t watch Freaky Friday until I was in my twenties, and only in researching this book did I really dive into a ton of body swap movies. But I’ve always been mildly captivated by the idea of body swapping. Perhaps this is due to being trans—I wanted a different body from a young age, and my subconscious likely spent a lot of time imagining myself as a femme person. When writing the book, though, I knew that I didn’t want to fall into the classic tropes of the genre. I didn’t, for instance, want to use any kind of magic as the impetus for the swap, nor did I want the characters to swap back upon learning their lessons. The body swap genre is pretty moralizing; often, the body swap is a kind of punishment (Freaky Friday, Switch) or it precedes a hubristic fall (Being John Malkovich). I didn’t want either to happen in this book, nor did I want Elijah to succumb to the things male characters have in other movies—though I tried to make it unclear how honest he is when claiming his goodness to the reader.

There are many instances in People Collide where a character—believing they are speaking to Elizabeth but in fact speaking to Elijah-as-Elizabeth—reveals feelings they never would to Elijah directly. For example, Elizabeth’s mother, Johanna, is harshly critical of Elijah and his family in a way she never would be to his face. Yet the body swap also permits positive types of exposure; for instance, we see at one point how Johanna is able to open up about her vulnerabilities to her daughter, Elizabeth-as-Elijah, in a way she has not been able to before. Can you speak more about how the Incident exposes the broken pathways of communication that so often exist in families?

The Incident is the most straightforward expression of the broken pathways of communication. But early in the book, Elijah notes that he and his mother have become closer thanks to the distance between them now that he lives in Bulgaria. Throughout the book, distance creates space for closeness, and that is most true in how the Incident shapes communication.

Similar to my thoughts about surrealism, I feel like characters are able to speak freely because they don’t believe they’re directly engaging with the person they’re talking about. The result is that characters, like Johanna, become brutally honest without meaning to—there is a reason she wouldn’t be cruel to Elijah’s face; it’s cruel! But personally, I always prefer sitting in the splash zone of cruelty if it means someone will be honest with me, and the Incident gives many of these characters their first opportunities to really be honest. This is also true of Elijah and Elizabeth, who speak more directly and honestly to each other after the Incident. Without the safety of their own bodies and personalities, they need to be especially honest, to communicate directly what they can no longer insinuate through the self-protective habits they developed in their bodies.

When Elijah attempts to conceptualize his transformation, he comes up against the limits of language itself. When in Elizabeth’s body, he never seems quite sure whether to call himself (herself? themselves?) “I,” “she,” or “we”—and indeed uses all three pronouns. At one point, he says “my mothers” in reference to his mother and Elizabeth’s mother. These shifting, discrepant referents made me think of The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, where Stevenson subtly shows us how his protagonist, Dr. Jekyll, confounded by his impossible duality, toggles between “I” and “he” when speaking about Mr. Hyde. With this, the English language, premised on a binary structure of self and other, “I” and “you,” is exposed as inadequate to capture the complexity of lived selfhood. We have, of course, come a long way since Stevenson’s time, but do you think of People Collide as adding to the conversation of the limitations of strict (and gendered) binary conceptions of the self?

I’m so glad you noticed this! I was worried this would come off as a flaw in the book—but you’re right to pick up on how Elijah is constantly pushing against the limits of self-understanding due to the limits of his language. I do hope that this book pushes the conversation forward on how people talk about strict gender limitations. It’s odd, because the book is fairly binaried on the surface. Elijah doesn’t actively exist in the in-between, at least not to anyone who might view him from the outside. However, his ideas about gender, and I would even say his gender, as Elizabeth, cannot be defined. I’m not even sure how I would define it, and I like the ambiguity, that his gender, in Elizabeth’s body, is one of aspiration and evolution. I don’t want to say futurity but hell: futurity. His gender is on the horizon and shifting, and I think it’s really exciting that he can’t really get a grasp of how to think about himself in terms of gender.

Toward the end of the novel, Elijah sums up “the point of writing” as showing people “what they can’t see on their own.” Do you think of fiction as an opportunity for engendering empathy, sympathy, or compassion—a chance to body swap, perhaps? Or is empathy something to be suspicious of, in fiction as elsewhere?

I don’t think that we should be suspicious of empathy. I think it’s a worthy goal, in the abstract. Who wouldn’t want to try to better understand another person? It’s noble. And I do think that reading fiction can help engender empathy or compassion outside of one’s own experiences. That said, I am suspicious of how books are sometimes marketed as something like Empathy Vitamins, where readers are told if they imbibe X novel they will better know how certain communities feel. Sometimes that happens, I’m sure. But that puts a lot of pressure on fiction to act as an ethical tool. And it assumes a few things: that the author accurately represented their characters, that the reader will absorb the intended (good?) moral of the book, and that the reader will then change how they interact with real people who are not characters in books (characters who, famously, are only engaged with at the reader’s discretion).

As Morten Høi Jensen pointed out in Gawker last year, a lot of heinous people have loved reading fiction. My hope is that reading might engender empathy, but more likely it only will if you’re already looking to think and feel outside your perspective; if that’s the case, then fiction is a wonderful way to broaden your views. It’s definitely helped me broaden mine.

While reading People Collide, I frequently experienced a kind of surrogate identity vertigo: when in Elijah’s first-person perspective, I found myself forgetting that the world around him saw him as a woman—and so I’d be momentarily startled when reminded about the Incident. In these moments, I realized I was being placed in Elijah’s perspective, who was experiencing a similar vertigo: Ah right! This random guy in a bar is inviting me to a concert because he’s seeing an attractive woman! Similarly, in the narration by Elizabeth’s mother, I kept forgetting that she is seeing Elijah as she’s speaking to her daughter. My confusion was that of the characters; the dramatic irony of the scenes became a dramatic irony I experienced too. Choice of narrative point of view powerfully shapes the substance of a novel. And your novel engages in a few narrator switches, with the above resulting effects. How did you decide whose perspectives we would inhabit in exploring the Incident and did you feel reluctant about ultimately leaving any perspectives out?

I’ve been obsessed with the notion of Gender Vertigo since I first read this question. I think it so accurately describes what’s happening in the book—and it seems to mirror the experience of being trans before publicly transitioning, when one’s experience of oneself differs greatly from how one is perceived. I’m so glad that comes through in the book.

I made the decisions fairly intuitively. Elijah is the main character, so his perspective is most prominently featured, but I included other perspectives and an omniscient narrator to fill out some holes in the book. However, I didn’t want to create a complete world, or to offer a pair of rival perspectives in the manner of a novel like Lauren Groff’s Fates and Furies. I think the book teases at that but pulls back before offering two parallel views. The book intentionally refuses to provide an equal number of perspectives because I think there is something exciting about not being able to see the full picture. Even if the book did feature an equal number of chapters in Elizabeth’s perspective, it would not have offered any firmer reality. The reader would still be choosing between competing realities, and my goal is for that to still be the case, for other realities to seep into Elijah’s perspective without them needing to fully appear on the page.

In People Collide, the mechanism by which the Incident occurred is not probed to any significant degree: the switch takes on the nature of an uncanny status quo. In Stevenson’s novel, by contrast, Dr. Jekyll is obsessed with devising and recovering the chemical formula for his switch—and then we have someone like Kafka’s Gregor Samsa, who upon waking up as another species altogether, simply carries on with his day.

At one point, Elijah states, “Being at the center of something enormous often means you’re the last person to make sense of what happened. Understanding is for outsiders.” Here, he’s speaking about a terrorist attack in Paris, not the Incident, but I couldn’t help but feel I should read this as passing the baton to us readers, telling us to make sense of the significance behind the Incident, with the freedom of interpreting an allegory. What was your process in deciding how to write about an enormous—because surreal—event like a body switch, in terms of how much to explain and how much to leave to interpretive and perhaps allegorical reading?

I think you’re definitely picking up on how that line speaks to the novel and the Incident, more generally. I’m not sure that I put too much thought into how to write about the body swap outside of simply conveying how it shapes Elijah’s immediate sense of self. I wanted to stay as closely grounded in Elijah’s experience as I could. And, for most of the scenes that appear in the novel, he’s forced to react to others’ interpretations of him. This leaves little room for him to try to find out what happened to him and Elizabeth. I knew that wasn’t a question I intended to answer, and if Elijah were to begin asking it then I would be tricking the reader into thinking I might provide such an answer. By turning away from that, I was able to focus on what most interested me: Elijah’s experience and how that shapes his relationship to those closest to him, and the world.

At one point in the novel, Elijah seeks counsel from a peculiar man he meets in a Paris hotel. Upon hearing Elijah’s story about the Incident, this man interprets it not as a literal change of bodies but rather as Elijah’s symbolic attempt to cope with the trauma of divorce. Elijah refers to him as “the craziest man I’ve ever met,” and it’s obvious to the reader that this man has a skewed sense of reality. But of course wisdom often comes from the least obvious sources, and I was tempted to read the divorce theory as a moment of divine madness: the reader being handed one possible interpretive key. Can you speak to the idea of People Collide as a metaphorical study of the disintegration of a married couple’s relationship, grief resulting from an actual separation, a prelude to divorce?

First off, I should say that I love bringing the word separation into the conversation, because Katie Kitamura’s A Separation was a huge inspiration for this book. I thought about it a lot while drafting—I can’t imagine writing this book without reading Kitamura’s first.

The novel can definitely be read as a metaphorical study of a separation. Elijah’s grief does mirror the grief that often comes after a breakup—missing the other person’s voice, their mind, their body, their movements, the unspoken sense of them that no other person will ever replicate. Taken metaphorically, Elijah’s desire to find Elizabeth is less about reconnecting with her than it is about finding the part of himself that he lost to the relationship—or it’s about him trying to recapture a version of himself that is already lost to him. He could move forward as Elizabeth, to do as the Instagram therapists recommend, take what he’s received from the person and move forward with his life, which is what Elizabeth appears to be doing. That he doesn’t suggests a sense of denial—which is also what prevents him from trying to figure out what happened, because to do so would mean having to accept it.

At one point in the novel, Elizabeth’s mother states that “stories are always changing…We change and thus we change the story, to better fit the person we are.” Since Elijah, our main narrator, is a writer, were you conscious of navigating the point of view of a writerly sensibility, at work in narrating the story, a sensibility that understands better than most that narrative formation is endemic to human experience and selfhood?

I was less conscious of Elijah as a writer than I was of him as someone who needs to tell a believable story over the course of the novel—perhaps I’m splitting hairs with that distinction. But even Elijah doesn’t really consider himself a writer; he demeans his talent, so I doubt he would be moving through the world as someone intentionally crafting a story. Nonetheless, he is delivering a narrative, he is trying to tell the story that he is Elizabeth. I don’t think this is about him being a writer; it is, as you say, that narrative formation is endemic to human experience and selfhood. His narrative of Elizabeth, as Elizabeth, is something like a game of telephone, the version he received and interpreted and re-presents to the world. It’s an imitation that strives toward accuracy but will likely never achieve it. I think this comes naturally to Elijah the way it comes naturally to anyone—we are always telling the stories of our own lives in order to maintain a firm sense of selfhood. But the book, I hope, exposes that very common process by separating the self from the story.

The main setting in People Collide is Bulgaria, and coming from Eastern Europe myself, I’m extra tempted to ask about this choice. In the “Western” imagination, Eastern Europe is so often a place of clichéd gloom, stock depictions of locals, and exoticism—a place for western tourists to see their disaffection mirrored back at themselves—that it’s always a pleasant surprise to see it as a place where, say, American characters simply head to and inhabit in a neutral manner: a real place rather than a cartoon. How did you come to choose Bulgaria as a setting and what function did you want it to serve?

I spent nine months in Bulgaria in my twenties, and I thought it could serve as a good setting in part because I wanted to resist those tropes of disaffection. In the novel, Bulgaria and the people who live there don’t mirror anything back to Elijah. Instead, they go about their lives, leaving no space for Elijah to interpret his experience through them—as Elijah says late in the book, he was a background character in their lives, not the other way around. Desi and Kiril, as helpful as they are to Elijah, are also too busy to sit with him in his grief for prolonged periods of time; they are constantly drawn back into work, to the register, to their own fantasies. They provide fleeting comfort but, like anyone, they’re more invested in their lives, just as Elijah is more invested in his.

I liked the idea of the book being set in a place that refuses to be made into a mirror. And I think the entire book resists the world-as-mirror impulse to interpret meaning in what are, to Elijah, unfamiliar surroundings.