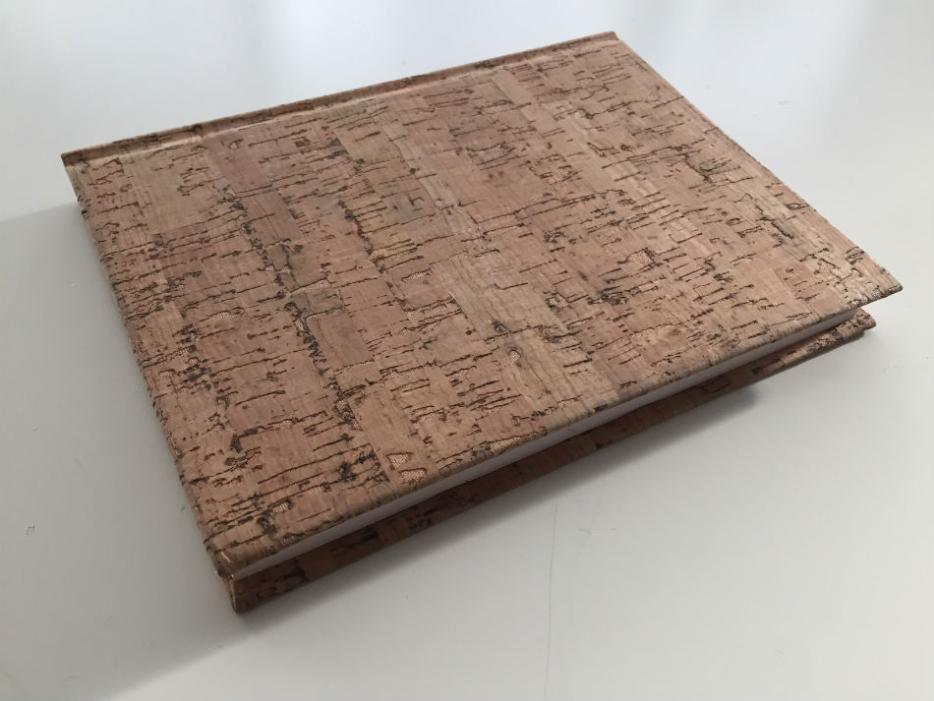

I met the Brazilian sculptor Liene Bosquê in her Long Island City studio a few days after she moved in. She was still unpacking and commented on the difficulty sculptors in New York City face finding spaces large enough in which to work. “When you make sculpture, it starts to become a problem,” she said. “You try to compact things.” She moved a box off a chair to sit down on it and invited me to sit on another across from her, next to a stack of her notebooks. The newest had cork covers and toothy paper—she explained she was craving more natural materials when she selected it, like the ones she’s often drawn to in her pieces. Her studio is smallish and full of tall racks holding Bosquê’s finished sculptures, and some unfinished attempts, as well as a large, assembled drafting table under a window framing an enviable view of the Queensboro Bridge and the Manhattan skyline. “I have to sketch more,” she joked, gesturing toward the city. “It’s something that I really miss, drawing.”

The view is perfect for Bosquê, whose work explores themes of urban preservation and history. But her drawings now are mostly plans for three-dimensional sculptures, molds, and installations. I first saw her work in the MoMA PS1 show Greater New York, where she was showing a piece called “Recollection”, comprised of dozens of hand-sized souvenirs from her travels, laid out on a plain, wooden table in a grid pattern resembling Manhattan’s. Though the souvenirs are found objects, she also uses them to make molds for other small sculptures in clay or plastic. With a background in architecture and an interest in history’s relationship to memory, Bosquê gives equal consideration to mathematical precision and sensory stimulation in her pieces—she has a rule that all of the souvenirs she uses in her work must be hand-sized, small enough to carry in her pocket as she picked them up on her travels over fifteen years. “Something that’s close to you,” she explains, as if keeping the memories of her travels close to her, too.

While living in Chicago, Bosquê began researching the architect Louis Sullivan and became interested in his idea of the ornament not as a superficial feature of architecture, but as something central to its function. “Most of the time you have this structure and then the ornament is the last thing, another layer,” she said. She found a way to combine the structure and the ornament in her piece Stockade, taking silicone impressions of tin ceiling tiles in a Syracuse building and using them to make molds for plaster bricks, with the ornamentation embossed on one side. After reading about the indigenous people of the area, she decided to assemble the bricks in a waist-high hexagonal structure evoking the stockade built by the Onondaga tribe to protect their village. The embossed sides face inward, each pattern slightly different from the one next to it but hidden from the outside. “It was kind of a way of looking to different times in history and trying to combine them,” Bosquê said.

She showed me a plan she’s working on in her current notebook, of a roughly nine-inch-wide replica of the Mỹ Sơn temple in Vietnam, set in the center of a two-foot table. She’s drawn it many times, from multiple angles. The length of each side of the bases of the temple and table are labeled, and on another page, there appears a Fibonacci spiral, also labeled with measurements. Above the spiral is written Bosquê’s name and the name of a collaborator. Beneath it, the words “spiritual polarities” and “polarity of forces” appear beside a column of words in binary relationship to one another. “The notebook just helps me organize my thoughts,” she said.