The first time the US experimented with solitary confinement in a supermax prison facility, the concept was abandoned as barbaric and retrograde.

Two hundred years ago, in Pennsylvania and New York, prison guards sequestered the worst of the worst in “segregated control units” at the Pittsburgh Penitentiary and the Auburn Prison.

The idea was that, absent the corrupting influence of other people, a prisoner would revert to his inherent goodness. Solitary confinement would bring the prisoner to a breaking point. As one Dutch commenter wrote: “Uprooted from his universe, the inmate in solitary confinement gradually becomes aware of his weakness, of his fragility, of his absolute dependence upon the administration, that is, on the ‘other’; thus he becomes aware of himself as a subject-of-need.” This, observers felt, was the first step towards reformation. You break them down, then build them up as productive members of society.

The experiment was an abject failure. Solitude didn’t change prisoners, it destroyed them. French observers, visiting the US to learn from the country’s advanced prisons, had praise for many aspects of the penal system, but they were appalled by the “the evil effect of total solitude”:

This trial, from which so happy a result had been anticipated, was fatal to the greater part of the convicts: in order to reform them, they had been submitted to complete isolation; but this absolute solitude, if nothing interrupt it, is beyond the strength of man; it destroys the criminal without intermission and without pity; it does not reform, it kills.

The practice was largely discarded. By the 20th century, solitary confinement was used sparingly, and generally only for short-term incarceration.

This is no longer the case. In California this week, officials reported that prisoners at two-thirds of the state’s jails, nearly 29,000 inmates, had begun a hunger strike, possibly the largest prison protest in California history.

The protests are centered around demands to change the solitary confinement practices at the notorious Pelican Bay. Opened in 1989, with the kind of ribbon-cutting pride usually reserved for a new hospital wing, Pelican Bay was simultaneously an enormous step forward and a return to the abandoned practices of the 19th century. This “state-of-the-art prison that will serve as a model for the rest of the nation,” said Governor George Deukmejian, and in many ways he was right. Pelican Bay was one of the early supermax prisons—a prototype for a new era of the penal system in which segregation and isolation would again be proactive tools to combat the problems that came with a booming prison population. How do you control thousands of prisoners without massive resources? How do you prevent violence and turmoil with hundreds of thousands of men locked up in close quarters? What better way to disrupt prison gangs than by separating them?

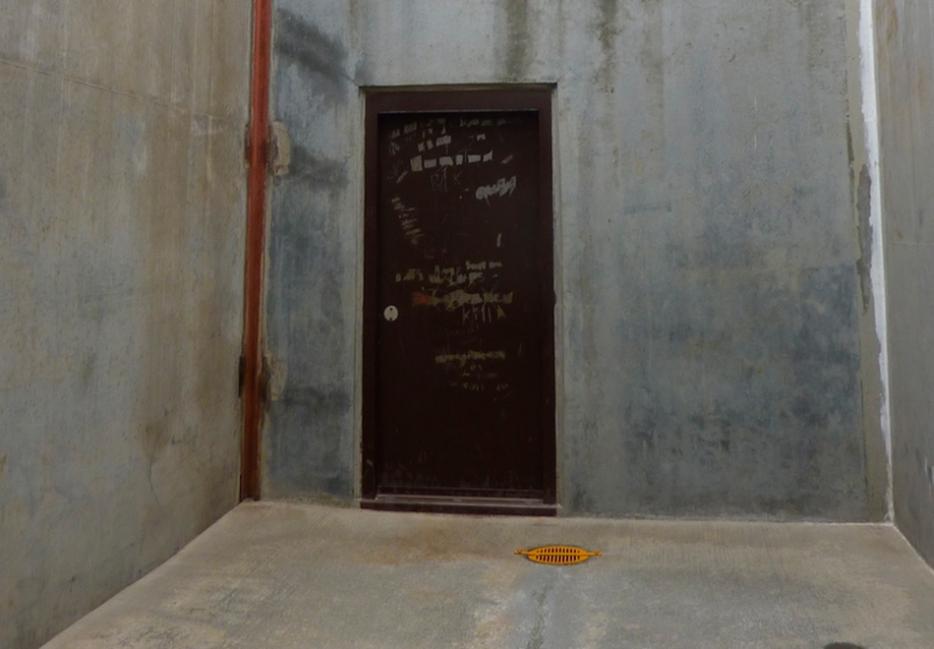

The prisoners at Pelican Bay spend 22 hours a day restricted to an 8 X 10 cell. The bed is poured concrete. The stool is poured concrete. There are no windows, just a fluorescent light that runs 24-hours a day. Food is pushed in through a slot. For an hour each day, the prisoner is allowed into “the yard”—a concrete room the size of three parking spaces. They are in the space alone. Then they’re put back in their cell.

In 2011, a UN expert on torture called on countries to end solitary confinement other than in exceptional cases: “Considering the severe mental pain or suffering solitary confinement may cause, it can amount to torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment when used as a punishment.” Anything more than 15 days should be prohibited.

In California, one of the hunger-striking prisoners’ demands is that solitary confinement be reduced to a maximum of five years. In 2012, a team of California lawyers launched a lawsuit on behalf of Pelican Bay inmates, questioning the constitutionality of long-term segregation. The Security Housing Unit, or SHU, holds gang members, as well as anyone prison officials believeis associated with a gang. One prisoner said he had not shaken another person’s hand in 13 years. He feared he’d forgotten the feeling of human contact. At the time, approximately half of the men in the unit had been there for more than a decade. Seventy-eight of them had been there for more than twenty years.

There is, of course, no real counter-argument that says this kind of treatment is humane. There’s no line-of-reasoning that says keeping a man in solitary confinement for twenty years is in society’s best interests. The argument is what it always is: that it really doesn’t matter how we treat bad people.

So, in California, the prisoners refuse to eat. It’s the kind of protest you undertake when you have exactly zero leverage except the general public’s vague belief that maybe another human shouldn’t literally starve. The Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation says the hunger strike is illegal. There will be consequences, they say. Some of these men have been in concrete box for decades; it is difficult to imagine exactly what these consequences could be.