Every week or so, Sook-Yin Lee and Adam Litovitz have a movie date. Then they talk about the movie. Discussed this week: Barbara, directed by Christian Petzold.

SOOK-YIN: You wanted to see Barbara. I had no idea what it was about. What struck me from the get-go was how incredibly spare it was. It simply begins with white letters against black: Barbara. And the first image it cuts to is—Barbara.

ADAM: And there’s Spanish guitar playing, which is the essence of spare evocation.

SOOK-YIN: Compared to a bulked-up movie on steroids this one champions minimalism and storytelling craft.

ADAM: If you break it down, buried within its minimalism are familiar types of stories: the spy story, a woman attempting safe passage, or escape. It was rendered in a simple and beautiful way.

SOOK-YIN: With very few brush strokes it conveyed so much. You’re forced to consider each detail, from the way Barbara applies her eye shadow, to her utilitarian skirt, her strap-on shoes, the bike she rides, and what she passes on her way to work.

ADAM: It’s minimalist, but it doesn’t shy away from being visually rich. It’s no coincidence that when she has to bury something important—which becomes the film’s MacGuffin, moving the plot forward—she buries it beneath a giant, wooden cross.

SOOK-YIN: There are layers of symbolism.

ADAM: The characters even analyze symbols. There are conversations about everything from Rembrandt to Turgenev. The characters are country doctors, but the script nicely weaves discussions of art into its story without them seeming terribly out of place.

SOOK-YIN: It’s minimal mise en scène meets maximum storytelling, where everything matters. The details are significant but spare. It wasn’t until halfway through the movie that I figured out what was going on.

ADAM: I was in the exact same boat. It was at the halfway point when I realized: ah, so that’s where this is set, and these are the conditions the characters are under. It was great to have that slowly dawn upon me. I had to work for that understanding.

SOOK-YIN: Barbara is a German suspense-mystery that unfolds in a rural setting, and the important plot point that becomes very significant more than a third of the way in is revealed by as seemingly innocuous an object as a pack of cigarettes. Because it’s a mystery, true to the genre, the audience has to piece together what’s going on.

ADAM: There’s a striking moment where Barbara goes into a restaurant with the owner up on a ladder barking at her. In the back, there are waitresses with their legs propped against a wall to prevent varicose veins. There are strange moments that you can’t help but wonder about.

SOOK-YIN: I was reminded of Roman Polanski’s ability to create suspense. Tension is ratcheted up by the sound of cars, the footsteps of people walking upstairs, a windy bike ride that threatens to throw Barbara off her seat– everything works together to create atmosphere and push the story forward. Barbara is a country doctor, relocated from Berlin, who has been incarcerated for who knows what. After release, she’s sent to a hospital in the regions where the staff approaches her with caution. There’s some unknown danger involved in her back story. She slowly befriends her coworker, Andre, one of the head surgeons.

ADAM: One of the central relationships in the movie is between Barbara and one of the female patients at the hospital, named Stella, a rebel and a runaway, someone constantly forced into work camps. What did you make of the relationship between her and Barbara? There’s the sense that Stella can only relate to Barbara. She’s brought to see a number of doctors, but can only connect to Barbara, who—like Andre—we get to see expressing care for patients. Was it maternal, or were they like siblings? Kindred spirits? Friends? Lovers?

SOOK-YIN: Barbara is a criminal, and society sees her as a wrongdoer. She befriends a young offender, who’s fled from incarceration, and contracted meningitis from hiding in fields full of tics. Stella’s a wild child who’s been in and out of the hospital several times, and she forms a bond with Barbara—the older criminal. Throughout the film is the notion of the criminal and the victim. The Rembrandt in Andre’s office is of a medical operation, and our perspective is of the unfortunate corpse being operated upon by clueless doctors following an instruction manual. We are firmly held within the gaze of the victim. The director, Christian Petzold, is looking at criminal-as-victim-as-woman. The personal has a larger political parallel. Barbara’s set in pre-1990 Communist East Germany, before the fall of the Wall. That’s why things are spare. There aren’t many luxuries. Petzold’s drawing a parallel between haves and have-nots of East and West Germany, focusing on the microcosm of the criminal as also the victim, and more specifically, the experience of a woman. The young girl trusts only Barbara, and Barbara is without child, but wishes to express maternal care. The film looks at women and career, and also their lack of rights.

ADAM: When we meet another woman who’s in a similar position as Barbara, there’s the additional sense that women are vessels, messengers by which men relay information between East and West Germany. It’s reminiscent of the original spy movies, like Notorious, which often depicted women as imperiled catalysts for male affairs.

SOOK-YIN: Like cattle or carrier pigeons. But, in East German hospitals, the male and female doctors are, in many ways, equal. It’s not a male dominated world, by any means. The men are soft, engaging women as equals. Yet, when we see Barbara interrogated by the secret police, and bodily probed, her personhood is robbed, and we see the plight of women.

ADAM: The most tender and supportive character is Andre. Even though he expresses ambiguity towards being lorded over in East Germany, he shows nothing but care for Babs.

SOOK-YIN: I remember interviewing a woman from eastern Europe, and we were talking about facial gestures. In North America, it’s “service with a smile,” but in Russia if you smiled, you were the object of suspicion. What do you have to smile about? Who did you brownnose to make you smile? In this movie, everyone has an impassive face, and so much of the story is told through subtle glances. Everyone’s trying hard to mask what they’re doing or feeling, and yet this is revealing.

ADAM: When somebody does smile, it means more than it does in most movies.

SOOK-YIN: When I realized this was the 1980s in East Germany, I was wondering if it would be an indictment of Communism, a political tract. You would think so. Everybody wanted to get the hell out of East Germany for an ideal life in West Berlin. Yet, the movie refused to be reduced to a didactic political debate.

ADAM: Various characters express disgust with the provinces, as if the rural setting has an innate horror to it. But, at the same time, we witness such beauty: seaside vistas, forest, and bike rides that can be taken even within ugly constraints.

SOOK-YIN: The locals feel like they’re seen as unsophisticated compared to the cosmopolitan Germans. There’s the sense that they’re living on the unfortunate side, the victims. There isn’t the choice of goods to buy at a department store, but there’s no lack of physical beauty in the landscape. I appreciated that the story transcended politics, and broke it down to the basic question: in a difficult situation, are you willing to save someone before yourself? It’s a hard question to answer.

ADAM: Another question is: what is it to truly save yourself? Is it to make one decision that might, at one moment, seem like an obvious path to freedom? Or, could the opposite path be a different sort of route to freedom? Are there different types of freedom to choose from?

SOOK-YIN: It took a trivial question like “can I help you?” and mined it for as much meaning as possible. It was very moving to me. After we went our separate ways after the movie ended, I ran into Cameron Bailey, who heads up TIFF and the Bell Lightbox, and I said that I was mesmerized by the storytelling technique. He told me that Christian Petzold is part of a group of filmmakers known as the “Berlin School”. Their aim is to tell stories with as few strokes as possible. Similar to the Dogme 95 constraints designed for authentic storytelling, the minimalism of the “Berlin School” forces the filmmakers to make every choice count, and focus on the strength of the story itself.

ADAM: It’s able to generate menace without resorting to a shock tactic, even once.

SOOK-YIN: No one’s hiding around the corner with a dagger.

ADAM: Occasionally, her passion explodes, like when she reunites with her lover. It gets down to brass tacks, with sexy stuff right away.

SOOK-YIN: Barbara arrives like Little Red Riding Hood with her picnic basket, in an unusual forest with trees without leaves or branches. We realize she’s come for a secret rendezvous with her lover from the West. The movie continually returns to love—Barbara and her lover, or the maternal love between Barbara and the orphan girl, or her love for Andre.

ADAM: I liked that the movie managed to set up two major mysteries: a medical mystery, and an international political mystery. When woven together, what might be a contrivance in other movies comes across as fate here.

SOOK-YIN: Barbara’s lover promises that when she crosses over to the west, she’ll never have to work again, and it sounds fantastic, but the look on her face shows she isn’t thrilled. She encounters another woman who’s having an affair with a secret service man from the West. This woman is excited to look through a department store catalogue for wedding rings. There’s a weird feeling of looking at pages and pages of diamond rings. Are they really so desirable?

ADAM: Even the woman’s crimped hair becomes a telltale sign of materialism.

SOOK-YIN: It also helped us locate the time period. It was in the 80s when we crimped our hair.

ADAM: There are snippets of the 1980 Moscow Olympics and of other Soviet-era vibes.

SOOK-YIN: The actress playing Barbara, Nina Hass, was extraordinary, keeping everything close. She looks like she’s in her 40s and isn’t a Hollywood babe.

ADAM: She’s 37. I thought she was pretty babe-ly.

SOOK-YIN: Yeah, but she’s gaunt and severe. She reminded me of a Fassbinder heroine. Andre was kind of pudgy. We’re not looking at perfect Romeos and Juliets here.

ADAM: For the most part, it was using naturalistic lighting, but at the end it took on a day-for-night look. If they’d stuck to natural lighting, you wouldn’t have seen anything in the night scene. They made the decision not to use glaring, artificial lights.

SOOK-YIN: I appreciated its classic storytelling: strong, intelligent, humanistic, and no frills.

ADAM: The pastoral setting didn’t hurt either.

SOOK-YIN: Usually suspense-mysteries have helicopters, a glass tower, people hanging off the side of buildings. This was all rustic orchards, pebbly pathways, people travelling on bikes.

ADAM: Even the moment with parachutists and people escaping beneath barbed wire seemed low-key.

SOOK-YIN: We saw the movie with my friend, who was annoyed by the portrayal of Communism because it didn’t support her own experience. Her family is Bulgarian and Czech, and her uncle married an East German woman and had no difficulty getting her out. On the other hand, I have family members who survived Communist China, where life was terrible, their rights horrifically revoked. You can argue about the veracity of any Communist experience, and yes, this movie chose a particular perspective, but to me the story went beyond politics. I realized that, hey, this is the 80s and reunification is around the corner. What’s more pressing are the questions of humanity that unite everyone on either side of the Wall.

ADAM: Humanity meaning no excessive cruelty exchanged between people.

SOOK-YIN: There are cruelties, but we don’t just see the secret policeman as a bad guy. We see him, as well, as a husband and father confronted by the perils of his own family life.

ADAM: Nor is there much regret. It’s simply life moving on for these people as they maneuver.

SOOK-YIN: Regular people forced into maneuvering within structures. It reminded me of Israel and Palestine. I recently saw Road Movie, an NFB documentary about a road that travels between Palestine and Israel, gathering people’s stories about it. Everyone just wants a good life, desiring the same things, while going about their day-to-day routine, but they’re pitted against each other when forced to live under constructed borders.

--

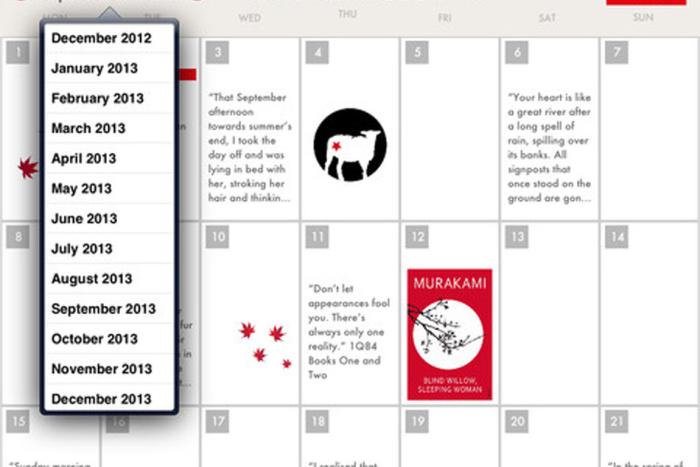

Illustration by Chester Brown