For all of humanity’s collective awfulness—our vindictiveness and stupid hats, humblebrags and genocides—there have nonetheless been moments in which we’ve proven capable of genuine decency and compassion. We can be good. In fact, on multiple, documented occasions, one human has helped another without expecting anything in return.

This is altruism, a quirk of evolution that leads one human being to give a coconut to a sick neighbour, never mind the cost to himself. It’s one of the traits that has helped us thrive, allowing us to cooperate with people well outside our immediate families or tribes to build the kind of large-scale societies that go far beyond what other creatures have managed. It’s that sense of common humanity that makes us not only successful, but tolerable, and sometimes even sympathetic as a species.

Psychologists have long studied altruism, but one of the major hurdles has been the fact that, like so much academic research, most altruism studies have been conducted on people who are comfortable, even affluent. Being generous as a psychology undergrad participating in an on-campus experiment, after all, is a very different thing from being generous under more trying circumstances.

Humankind’s essential altruism in adverse conditions has remained understudied. When things really go wrong, how will we respond? Rather than taking the “circuitous route of reciprocal altruism”—doing unto others, sharing precious bottles of water with the hope that somewhere down the road others will do unto you—why not just hoard resources and protect your family?

Devising a study that tests people’s altruism under adverse conditions is difficult, for obvious reasons. A recent study led by University of Toronto professor Kang Lee and published in Psychological Science, however, used an unfortunate disaster to create a rare natural experiment.

In 2008, the researchers were in Sichuan, China, beginning a study on empathy and altruism among children. Their method was fairly simple. Using groups of six- and nine-year-olds, they got children to play a “child-friendly dictator game.” Each student was seen by a female researcher individually and invited to pick out ten stickers for themselves. They were then told they could donate some of their stickers in a sealed envelope to an anonymous classmate who wasn’t participating in the study. The researchers blindfolded themselves as the children made their decisions, assuring them they weren’t looking at how many stickers they chose to donate. Later, of course, they opened the envelopes to see how altruistic each child had been.

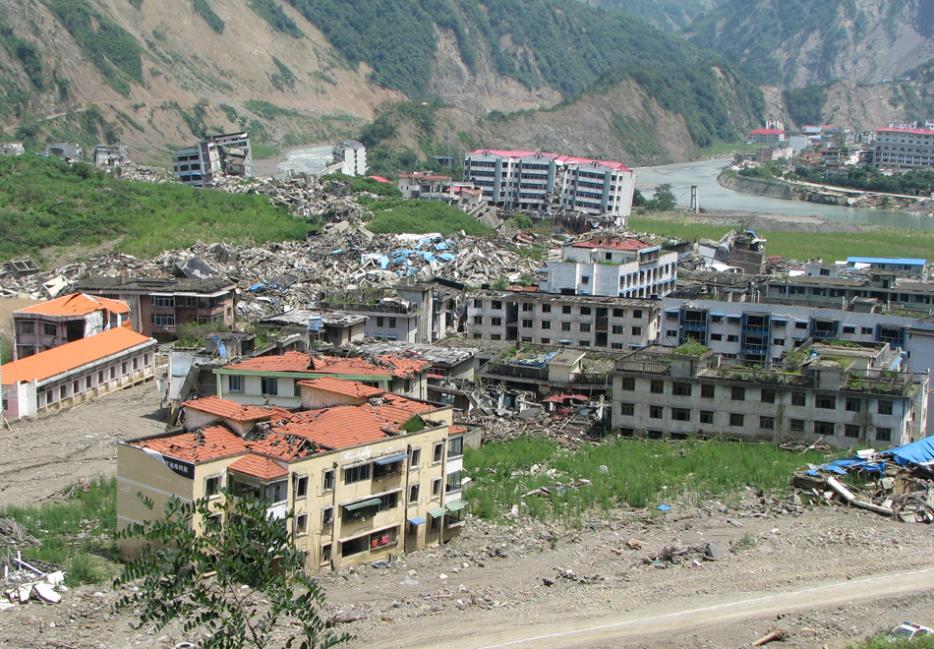

The researchers had just completed the first phase of their study when disaster came. The magnitude 8.0 earthquake that hit Sichuan on May 12, 2008, devastated the region. During two minutes of shaking across a 240-kilometre fault, mud-brick houses and concrete buildings collapsed. Schools that weren’t built up to code crumbled. In the end, the earthquake killed 87,150 people and left millions homeless.

The researchers’ study quickly shifted to look at the way the disaster had affected the children of area. A month after the quake, the researchers tested a new group of six- and nine-year-old children from the same school. The kids had been poor to begin with, and the quake had turned their lives upside down. Ninety-five percent of the kids in the group were homeless. Thirty-six percent had at least one parent who was now unemployed. Eight percent had family members who had been injured by the disaster.

When the kids were given the sticker test, researchers found a marked difference. The six-year-olds had become more selfish, dropping their donation rate in the wake of the disaster. The results are in keeping with the way we think altruism develops in early childhood. Toddlers remain innately selfish, but sometime shortly after that we seem to develop the ability to share and empathize with others. At six, the researchers suggest, a sense of altruism remains a fragile thing. A devastating event is enough to knock a child into the selfish hoarding of early childhood.

The nine-year-olds, meanwhile, had grown significantly more altruistic. They gave away a mean of four stickers, versus just a single sticker before the quake. Facing awful conditions, having lived through a scarring ordeal, the eldest children became more generous, not less. A natural disaster seemed to create a moment of solidarity, of increased empathy.

This is, of course, the best side of humanity. It’s the response we see whenever a tornado tears through a small town or a hurricane devastates a country. It’s why Americans get strangely wistful talking about the days after 9/11, when neighbours checked in on one another and it seemed like anything was possible. It’s a sense of heightened altruism that comes with terrible hardship, but quickly disappears as the event fades from memory.

Three years later, when the researchers returned to the region, they found that children’s altruistic giving had returned to pre-quake rates. The older kids had once again become stingy with their stickers. The effects of the disaster had been powerful, but brief. Humans react well to adversity, it seems. We just quickly forget.