In 2008, hip clothier Juicy Couture launched what might have been one of the most ill-conceived advertising campaigns ever. Plastered all over its flagship Manhattan store and inside nearly every fashion magazine, you could find the image: waifish models posed on a California beach, clad in Juicy’s iconic velour and terry-cloth gear, all sporting different colours, with a bold Gothic-type tagline declaring, “Let Them Eat Tracksuits.”

In any other year, you could have chalked up such a marketing decision to the brand’s self-conscious frivolousness: this was a company, after all, that had convinced millions of women that $200 was a small price to pay for the luxury of loungewear. But 2008 was not just any year: It saw one of the worst financial collapses of the modern era. It was the year when phrases like “toxic assets” and “too big to fail” would become ubiquitous, when 2.3 million Americans would lose their homes to foreclosure. It’s also when Juicy Couture decided to offer up the nourishment of conspicuous consumption.

The designer label would prove just as short-lived as its historic inspiration. Last month, following years of dismal sales, Juicy announced it would shutter its U.S.-based flagship stores and scale back production in the country (the brand will still continue to operate in Asia). Juicy-branded items, meanwhile, will be stocked at discount retailer Kohl’s for an indefinite period of time—a long way from the pricy shelves at Bergdorf Goodman. Au revoir, velour.

It seems especially ironic now that Juicy wouldplay on the words of Marie Antoinette, a monarch as notorious for her vapidity as for her lavish spending on loungewear. But the story of Juicy is a strange mixture of aspiration and extreme wealth. From the outset, the company labelled its clothes with a regal crest—the initials of its founders Pamela Skiast-Levy and Gela Nash-Taylor, crowned and flanked by lap dogs—along with a reassuring, “Made in the Glamorous U.S.A.”

The label’s origins, however, weren’t quite as glamorous as either its velour-rendered suits or logo suggested. Skiast-Levy and Nash-Taylor started the company with a couple hundred dollars and an idea to produce curve-hugging T-shirts and boot-cut velour pants. The House of Juicy wasn’t built in the tony neighborhoods of Los Angeles; it came from the industrial flatlands of Pacoima. A working middle-class neighborhood produced the clothes that would eventually become staples of Rodeo Drive.

“We started playing with the idea of creating a terry-cloth uniform,” Skiast-Levy and Nash-Taylor wrote in their recently released memoir, The Glitter Plan: How We Started Juicy Couture for $200 and Turned It into a Global Brand. Oversized sweats were for working out or lounging in the privacy of home; leaving your house in them signified a resounding “I don’t give a fuck” about either fashion or personal appearance. But the pair “went the other direction, giving those basics a sexy, body-conscious shape. It was all about an uber-flattering silhouette, kind of couture-esque really.” Skiast-Levy and Nash-Taylor had struck zeitgeisty gold.

By 2001, with the housing market booming and incomes inflating, Juicy Couture sold the optimism of becoming ultra-rich. They designed the nonchalance of wealth’s casual wear, radicalizing lounging and branding languidness—it was a uniform for the public display of not doing anything. And the tracksuit trend spread like a hot-pink wildfire: In the early 2000s, Juicy estimated about $200 million in sales; by 2008, that number was up to a reported $605 million.

Enter Antoinette. The last French queen was a perfect silent spokeswoman for the brand, it seemed: a boundlessly feminine style icon who loved lap dogs and lived in a blingy McMansion. She was also a champion of radical lounging, singularly rejecting her primary job—to don the corsets and heavy gowns of a monarch—in favor of the chemise, a kind-of precursor to the Juicy tracksuit, and a sign of the decadence afforded by incredible wealth. After all, only a queen could afford the indulgence of pricy leisurewear.

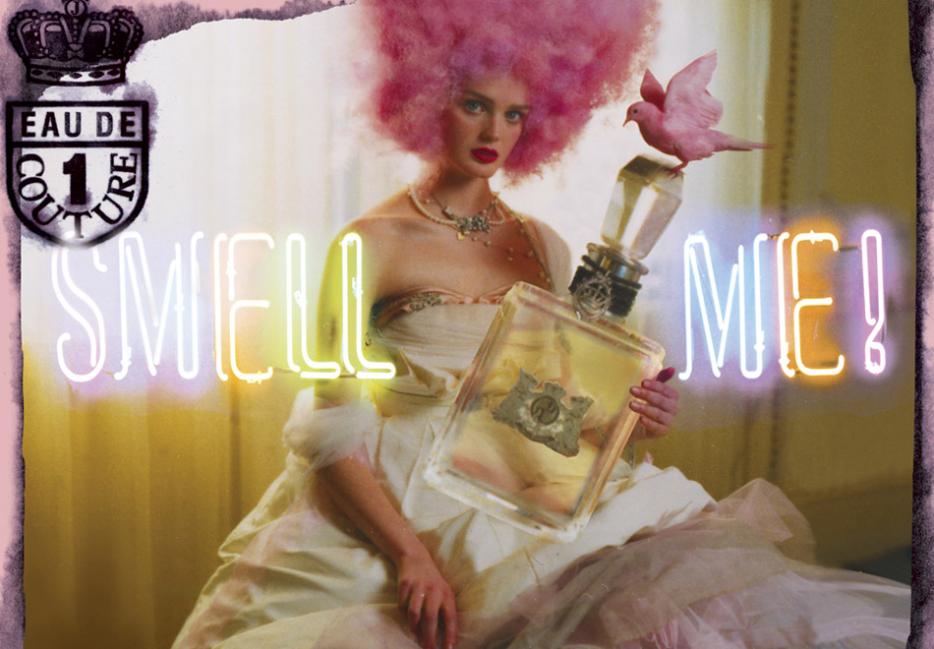

At the height of the label’s popularity, you could buy a Juicy-themed Clue game featuring a rosy-cheeked painting of the queen emblazoned across the box. Its perfume campaign, too, fashioned itself à la Antoinette, featuring models with elaborate hot pink wigs reminiscent of the queen’s fashionable pouf.

Juicy Couture sold the perception of royalty to one-percenters and aspirational shoppers alike. Its candy-coloured tracksuits quickly became the look of nouveau-American nobles—celebrities, sure, but newly moneyed housewives and their well-heeled children, too. It’s no coincidence that Amy Poehler’s middle-aged mom in Mean Girls sported the same cotton candy-pink Juicy tracksuit that twenty-something Paris Hilton made famous only a few years before.

But the success couldn’t survive the Great Recession. By 2010, nearly every major department store had dropped the company. Skiast-Levy and Nash-Taylor left the company, and its corporate owner, Liz Claiborne, Inc., tapped ultra-hip designer Erin Featherston to consult. Not even the industry-loved Featherston, fresh off a successful New York runway show, could revive the dying brand, though: retailers chalked up disinterest to bad sizing and repetitive styles, but American consumers, it seemed, had lost their taste for Juicy.

After the attacks on New York and Washington in 2001, President George W. Bush instructed Americans to exercise their patriotism and exult in normalcy by “enjoying life”—shopping and visiting Disney—and the cool and comfortable Juicy tracksuit was a perfect outfit for the leisure-spending of the Bush years. But by 2008, the political rhetoric of consumption had been usurped by the financial collapse, replaced with one that emphasized getting Americans back to work. The velour tracksuit was anathema to the actual workplace; its branded indolence seemed like a gauche choice for filling out unemployment papers or figuring out what it meant for your mortgage to be underwater. Historical fact: when the revolutionaries stormed Versailles, they went first for the Queen’s clothes, tearing them to shreds in a frenzied display of anger and resentment.

So Juicy will no longer produce its iconic tracksuits, though museums such as the Victoria and Albert have stashed a few away for future generations. Skiast-Levy and Nash-Taylor walked away millionaires, and their new couture line, Pam and Gela, sells $150 crop tops with words like “Vague” emblazoned across them. It’s Juicy-lite, capitalizing on the affluent leisurely aesthetic that once formed Juicy’s core, but with the instantly recognizable Juicy flair of rhinestones and garish branding replaced by an understated vibe of dark palettes and animal prints. There’s not a tracksuit to be seen, and the new line’s overtures to conspicuous consumption are more ambiguous, but, with its high price tag and studied nonchalance, shades of the old ostentatiousness still haunt the margins.

The tracksuit is dead; long live the tracksuit. Viva la Juicy.