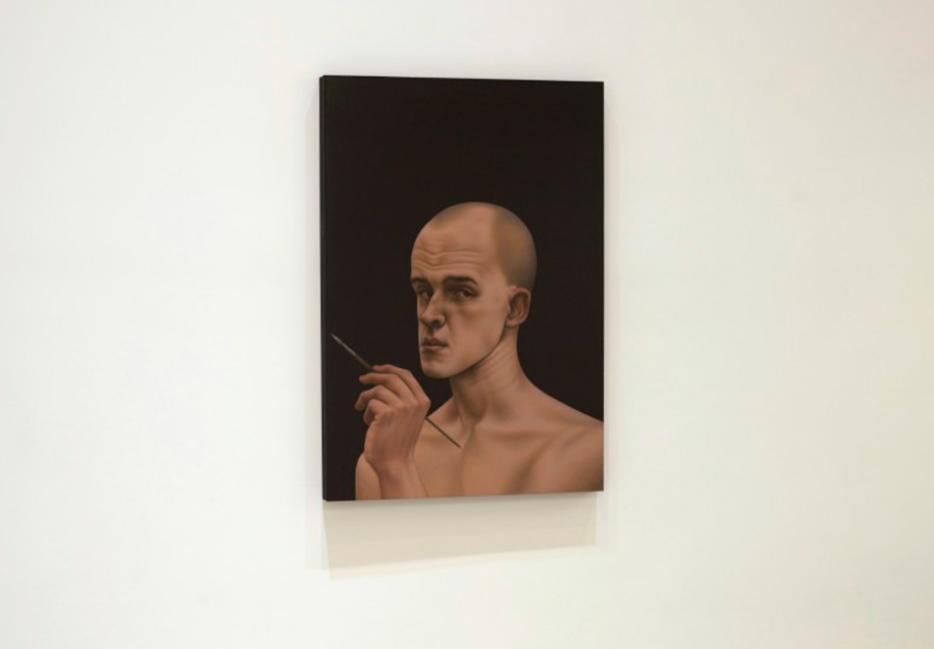

When I met the young painter Matthew L. Miller at his ongoing solo exhibition in New York City’s Chelsea gallery district, I did a double take. Miller’s actual, physical face—mostly-shaven head, pointed nose, prominent brow—floated right in front of its exact twin on a panel hanging on the wall. The skin of the painting shared the same sallow tone; its angular bones followed the same precise lines as its counterpart. It was a stunning facsimile. As I later discovered, though, the face in the painting wasn’t really Miller at all.

On view at Hansel and Gretel Picture Garden / Pocket Utopia, a composite space that combines the programs of two formerly separate galleries, Miller’s show is entitled Can’t You See It, I Am One. The reflexive title underlines the ostensibly obvious fact that the half-dozen paintings sparsely arrayed around the gallery space are self-portraits—what other subject would be so content to sit for all of them? The shifting angles and the odd glances—at times reminiscent of “smizing” or the Sparrow Face trend—should be familiar to anyone who has ever labored over a selfie.

In each piece, Miller’s face, slightly more gnarled and distant than the one standing in front of me, is shown from a slightly different perspective, with minutely varying expressions, shading from intense concentration to eerie condescension directed at whatever the figure is seeing. Or perhaps I’m imagining it? The faces, as well as the bodies in two paintings—one in which Miller’s two-dimensional twin is shown carving a wooden bust, another in which he’s holding a paintbrush, its tip lofted into the air—force an emotional reckoning on the viewer. Their mottled-flesh surfaces are intensely alive.

Yet this twin is not quite a real human. Miller constantly refers to the figures in the paintings as “he” or “they,” verbally externalizing their presence from himself. “They” are not Miller, though they look just like the artist. “I want them to be painted types,” Miller said. “They’re from a painted world.” Miller sees these laborious self-portraits—“I only do a couple of these a year; I have less than 15 altogether,” he said—as meta-commentaries on the act of their creation. “The subject matter of my work is self-portraiture,” he explained, “not him.”

*

The medium of self-portraiture has its own long history, wending its way first through artists such as the 15th-century Jan van Eyck and 17th-century Rembrandt, who, as history’s first selfie addict, portrayed himself over the course of his lifetime variously as a struggling genius, a wealthy merchant, and, finally, the august old master we now remember him as. Van Gogh later took up the thread, along with the inveterate bohemian Gustave Courbet, and Pablo Picasso, who often masked himself as a voracious Minotaur. Lately, digital artists such as Petra Cortright and Rollin Leonard have been turning selfies into vehicles for art.

“Any time I can get someone to stand in front of my paintings and maybe put themselves in my place, or get them to become more conscious of how it’s made, I’m doing something right.”

These artists most often used self-portraiture to reflect on themselves and their own work, just as we use our selfies to communicate certain ideas about our identities and our lives. But Miller is after something different. His paintings are about deconstructing how the self-portrait works. “I enjoy thinking about what a selfie is,” he said. “Breaking it all down.”

Think about the staging of a self-portrait. The artist sits in front of a mirror in which she sees her own face, then copies that image onto her canvas. “There’s this whole relationship that’s already in place in portraits—object, sitter, painter, mirror,” Miller said. “I’m fascinated by that schematic area, this given program.” Miller’s paintings occur when the “nodes” in that program, as he calls them, start to shift and become unsteady.

Miller’s painting of himself with a half-carved block of wood, an image depicting another act of self-representation, is a perfect example. On its surface, the piece appears to be a painted self-portrait. But the figure we see reflected in the theoretical mirror is carving, not painting—the figure embedded in the painting would seem to be painting himself as a sculptor. It’s as if someone took a selfie and it came out in marble instead of pixels. In Miller’s other painting in which his archetypal alter ego points his brush skyward, the sly look he gives out of the frame seems to communicate that he knows we know he is creating himself, lying to our eyes as we try to puzzle out his game.

Do you look at your own face while you paint? I asked Miller. “It’s more like I know my own face, my own painted face,” he said. So is it really him in the paintings? “I see the whole object as having a lot more to do with me personally in terms of self and identity than the image,” he answered. “The image”—the “him” of the works—“is just a feature of the painting.”

As abstract as this node-switching sounds, it’s really no different from composing a selfie. Every time we shift the phone’s angle slightly in its orbit around our faces, we chip away at the reality of the resulting self-portrait, envisioning an idealized form of ourselves, like Rembrandt’s portrayal of himself as a successful businessman. When we send those selfies out into the world, we affix them to virtual gallery walls, enshrining them as our truest self-portraits—when, in reality, they are anything but. Miller subverts that seamless process of self-creation and underlines its instability instead of harnessing it to his own ends, pointing the mirror at his viewers instead of himself. “Any time I can get someone to stand in front of my paintings and maybe put themselves in my place, or get them to become more conscious of how it’s made, I’m doing something right,” the artist said.

*

I recently went to New York’s Metropolitan Museum and sat down in front of a large Rembrandt self-portrait from 1660, created less than a decade before the artist’s death. In it, Rembrandt is dyspeptic, slightly grumpy, a cynical cast to his dark eyes. The piece’s brushstrokes are delicate and more visible than in Miller’s work, despite springing from the same inspirational sources in the Northern Italian Renaissance; Rembrandt’s flesh, hair, and clothes dance with flashes of light. But the entire figure eventually melds into the uniform brown of the canvas’s background, cut off around the torso by a gilded frame.

I’d already seen Miller’s work, which played with the same genre of painting that Rembrandt pioneered, casting its supposed truths into doubt. The Rembrandt is a relic from before self-portraits were within the reach of everyone, rather than the sole province of artists. But Miller’s postmodern tactics now color the older piece, building on the long tradition of self-portraiture. Looking at the rose-tinted wrinkles in Rembrandt’s face and following the direct path of his gaze out at the viewer, which remains breathtakingly intimate and human after more than three centuries, I couldn’t shake the suspicion that there might be something happening just beyond the portrait’s edge, an outstretched arm moving to lift a brush or a body shifting to take better advantage of the mirror’s placement—a specter of life waiting for me to look away.