Besides finally giving us the chance to see one of our cats on a hundred-dollar bill, Merna Foster's petition to put Canadian women back on Canadian currency is notable for being one of the few major public responses to our latest bank notes that hasn't focused mostly on how they could melt. Even in the plastic age, money is ubiquitous enough—and attached to enough other, far more anxious, concerns—that it's easy to forget that it's designed with a specific purpose. Still, the designs on each bill can sometimes feel like a mainline into the wavering national identity, or at least the intentional and unintentional national bugaboos of whichever government got final say on the pictures.

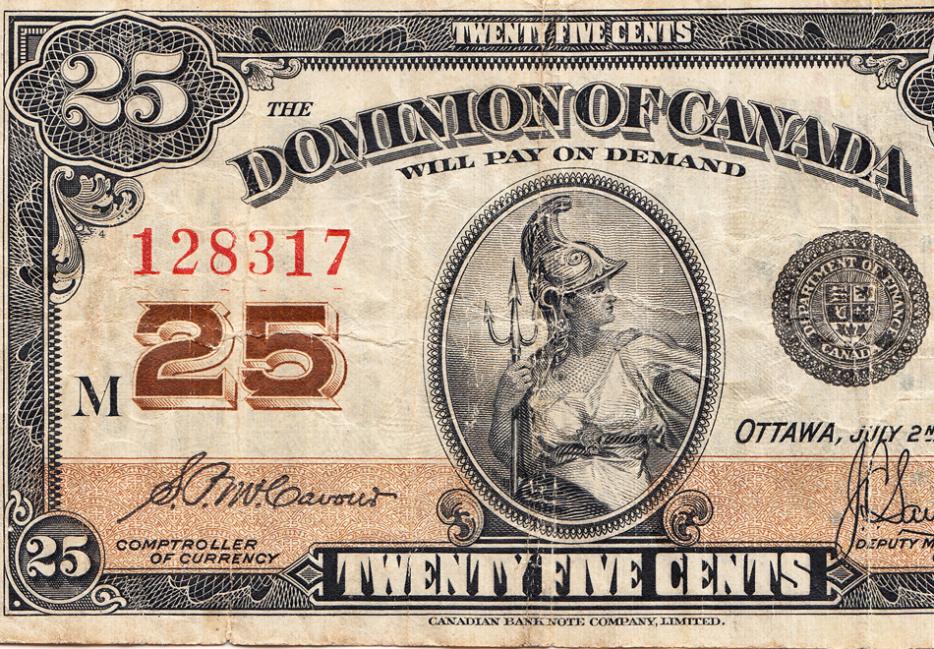

The country's earliest notes revealed a Canada with a pretty serious inferiority complex, giving up essentially all of the common fronts to portraits of the king or queen, and using the back to embody vague ideals with figures from classical myth—Hermes and his generic progress, Athena and her wisdom (and Windsor Castle); these were roughly as evocative of a distinct Canadian sensibility as Monopoly money, except the Parker Brothers stuff didn't reek quite so much of worldly pretension. The 1954 series swung almost entirely the other way, keeping the regal front (now just the queen), but trading the backs for distinctly Canadian scenes, albeit ones firmly rooted in the Canadian art tradition of portraying the country as essentially a vast, untouched wilderness—they even aimed specifically for rural or wild scenes that were not already overly familiar. (The lead designer, Charles Comfort, was an early Group of Seven admirer, a sensibility he put into practice even further as director of the National Art Gallery in the '60s.) The scenes have almost no sign of human habitation, much less industry; they're Canada as Arcadia, though demonstrably Canada nonetheless.

By the '70s, we were finally ready to acknowledge that we had at least spoiled the wilderness a little, if only so we could crow more about our mastery of it. The Scenes of Canada series—note the explicit nationalism-baiting, this also being the first time we put our own Prime Ministers on a run of heavily used bills—still leaned prominently on nature, but in this case emphasized our natural bounty: Inuit hunters and tourist destinations and fishing villages, even an oil refinery, Arcadia put to good use—the tension between our bucolic past and our growing desire for grown-up country recognition played out, fittingly enough, right on the money. The late-'80s Birds of Canada series was a return again to Canada's favourite self-image—practically speaking, the obvious but intricate pictures were supposed to both aid the visually impaired and make counterfeiting more difficult—but was set off by the fronts, which included various views of the Parliament buildings: these fowls do have a government.

It's only been in the last two series that our officials seem to have finally shaken off our attraction to the wild. The Canadian Journey series, launched in the early 2000s, explicitly weaved in Canadian culture, mixing quotes from literature and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in with distinct Canadian scenes—including hockey and the war memorial (yes, even in those pre-Harper days) and the Famous Five, the removal of which stoked Foster's petition to begin with.

The latest batch, The Frontier Series, is, as with most modern Conservative attempts at cultural influence, not really less desperate than others to advance its preferred vision, but considerably more ham-handed in its execution. Gone is the explicit calling out of cultural history, replaced entirely with the products of industry. Where once we would even be willing to show the middle steps of oil production—although just imagine the complaining if they rolled out a twenty with an oil sands dump truck on it—now it's just the world-changing results of all that economic activity (well, and a war memorial), Canadarms and insulin and a retrofit ice breaker that was originally named after Sir John Franklin, our favourite recent metaphor for our northern resource birthright, whose doomed expedition was finally located just as better-equipped ones start probing the bounty the arctic may yet reveal.

There is some kind of progress here, even if it's not necessarily the kind that the bills are so eager to suggest. The idea of Canada as vast, untouched wilderness was wrong even when it was notably promulgated: first as a very convenient forgetting of the aboriginals who were erased off pages and canvases in the name of the tabula rasa; later, as a nice way for those in the narrow belt of power along the St. Lawrence to convince the hinterlands they were essential for something other than economic exploitation. Now that more than four-fifths of us live in cities, that's not a narrative that can credibly exist outside of tourism ads, and yet some of our most quintessentially Canadian stories seem to remain in survival mode, living in a metaphorical landscape where nature still holds sway, as if entire generations haven't grown up with central heating and central air.

But then there's the sticky reality of the fact that it's an official narrative, and one that is conveniently turning us away from the notion of natural beauty just as that idea becomes politically dangerous. This is by no means limited to the current government: cultural products can be as much of a distraction as industrial ones, however much they speak to our softer progressive sensibilities. Governments of all stripes are happy to forget whatever needs forgetting when it comes to making money; the products of people took prominence on our money just as it became necessary to start strip-mining northern Alberta in order to turn us into an energy giant. Anyone who wants a problem-free economy in that reality is going to think twice about promoting unspoilt mountain vistas.

Fraught as it was, the promotion of Canadian Arcadia was at least a cogent identity, something that a narrow but prominent section of the country could make sense of, and that could be refashioned for easy enough selling to everyone else. As we—rightly, necessarily—move past it, though, it is worth remembering that there are many reasons why we choose to forget. Money is perhaps not a particularly good one.