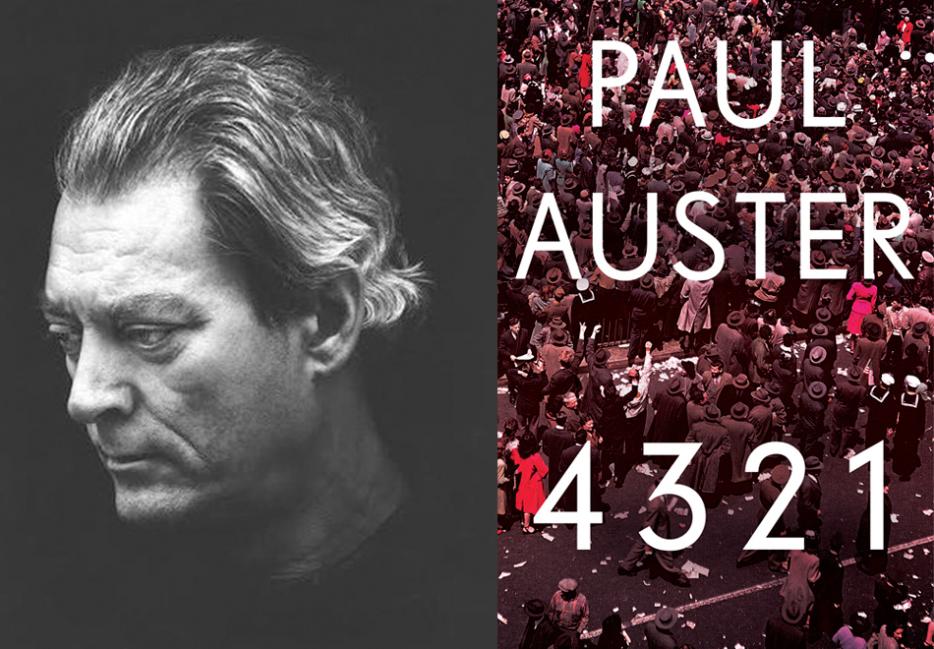

4 3 2 1 (McClelland & Stewart) feels a bit like Paul Auster going to 11. His latest novel is something of a maximalist interpretation of his lifelong fascination with happenstance, metafictional gamesmanship and American mythology. It follows the life of one boy, Archibald Ferguson, in four different configurations: spurred by the fate of his father’s furniture and appliance shop, each version of Ferguson is left to spiral out into an entirely different life, finding his own path from New Jersey youth to—well, it depends on the Ferguson, really.

Though it has lost the genre play of Auster’s early work, it has replaced it with something like sociopolitical grandiosity. 4 3 2 1 is, in a sense, [sort of] the ultimate American tale: beginning with an immigrant who bumbles his way through the processing centre of Ellis Island, it is a kind of oblique testament to the potential of the American endeavour. You really can be almost anything in this land, or at the very least be a lot of different variations on the same basic story.

With the drumbeats of history and politics marching each of the four Fergusons along, Auster takes us through almost every aspect of a Jewish New Jersey adolescence, every possibility, joy, horror, heartbreak, erection, ecstatic triumph and cruel disappointment of a young man growing through midcentury American tumult. It is a hearty scratch for anyone who has ever felt the itch of what if, a deep dive into the rocky, capricious, chaotic waters of life—and then it comes up for air and dives back down three more times.

David Berry: One of the Fergusons becomes a writer—well, I guess they all become writers in some capacity, but one becomes a novelist—and he describes the experience of his first review as, “five satisfying tongue kisses, a friendly pat on the back, three punches to the face, one knee to the balls, one execution by firing squad, two shrugs.” You seem to get your share of criticism these days; how has it been to wade back into the responses to your first book in six years?

Paul Auster: First novel. I wrote three books in between. I don’t know why everyone says that: it’s not as though I was twiddling my thumbs the whole time. But I don’t read too much of it. I’ve gotten some very nice responses. Some very awful responses. That’s pretty typical for me. It’s nothing in between: it’s either love or hate. What can I do? I’m a target. People are gunning for me. I find it ridiculously stupid, unfair— they don’t read my work, but they have an opinion about it. Other people are more open-minded: they see what’s there, and they respond to it. There seem to be some reviewers who want to say what the book should be, rather than what it is. It’s as if someone was to say, “Well, Ulysses, it’s so boring. Why isn’t Leopold Bloom planning a bank heist for that day? That would be much more exciting.”

To think that this one could have had four bank heists. But I’m curious, then, about what is there: what drew you to this conception of a novel of multiple timelines, or parallel lives, or whatever you might want to call it?

Number one would be this eternal fascination with “what if?” I’m always playing out possibilities of what might or might not have happened. But I think, deeper than that, was a thing that happened to me, which I have written about: when I was 14, a boy was struck by lightning next to me, and killed. That has haunted me all my life. And it has certainly changed who I am. That experience—but I wasn’t even aware of it when I started. So much is happening in the subconscious. You write your way into a certain kind of clarity. It starts as a blurry muddle of mess, and then it starts to take on definition.

The experience of writing a book might be like that, but what about that actual experience, of almost being hit by lightning? You’ve talked about it before as an important event in your life, and I feel like you could trace that through a lot of your fiction, the idea of this sort of happenstance, random occurrence. Did you have anything like that realization at the time? I mean, it’s literally a bolt out of the sky, showing you how random things can be.

No no no no no. It’s something that sneaks up on you over the years. I distinctly remember, after it happened, it never occurred to me to think, “If it had been five seconds later, it would have been me.” That never crossed my mind until years later. Because somehow, an event is an event. You take it for what it is. It’s only on reflection. This book in its entirety is almost all that reflection. Remember the conversation that Ferguson 4 has with Noah, his friend/cousin, about the two roads: You have to get to an appointment, and there’s the main road and the back road. You can’t really know if you’ve made the right decision, because you can’t be in two places at the same time. And he says that’s why we invented God, because he can be all places at the same time. These are the kinds of things that have always interested me, so I decided to play it out in a big book.

I think those what-ifs are always appealing to a certain kind of person. Although I think, in a strange way, thinking about those actually makes me feel more like a determinist. Thinking about all the things that could have been different, that were maybe just happenstance, makes me think about the ways they were actually kind of causal. I think of it almost in the Guns, Germs, and Steel sense, the way all these little things shape outcomes: if you go far enough back, I find it easy to think, “Well, what else could this really be.”

I’m not so sure about this. In my previous novel, Sunset Park, Lorenzo Michaels, the novelist, is having a conversation with his friend, and talks about wanting to write a novel about things that didn’t happen. There are many wars that could have happened, but didn’t happen. A lot of huge wars that stupidly could have been avoided—the Cuban Missile Crisis being one that didn’t happen, Iraq being one that did, for no reason. It was built on lies that the Bush administration told the American public, and has destroyed a whole country, a whole region, and we’re still paying the price for that blunder. But it didn’t have to happen. Another what-if: what if Ralph Nader hadn’t run for president? Or what if the Supreme Court hadn’t been the political hacks they were and given the election to Bush? What if Gore had been president? He never would have invaded Iraq. So likely there’d be no ISIS today. No so many things. It just so easily could have come to pass that way. I can’t believe in this determinism. It doesn’t make sense. It’s just how things fall out. They don’t have to be that way.

Right, but I think that sense of spiralling out you’re talking about, that’s what sort of trips me up. To keep on the 2000 election: sure, if those judges had decided a different way, we don’t get ISIS. But maybe you wouldn’t have been on the court, in a position to make that decision, if you weren’t the kind of person who would have decided that way. You wouldn’t be Ralph Nader if you weren’t the type of person to run a more or less hopeless presidential campaign. The tendrils seem so vast in every direction I almost feel like you have to assume it worked out that way for some particular reason—not in the sense of, like, God ordained it, but maybe just something like, “Well, it started in this position.”

I think what I want to say about the lightning experience is this: anything can happen at any moment. Period. At any given moment things don’t have to happen the way they do. It’s an accident. An accident by definition is something that doesn’t have to happen. It’s not necessary. It’s a contingent fact. The only necessary things that have to happen, I suppose, is that we’re born and we die. Everything else is a contingent fact.

Speaking of contingent facts: since this is a novel, and you’re not literally God, there are a fair amount of concordances between the Fergusons. They’re all writers, of a kind, they all end up dating or interested in the same woman, and so on. Is there something essential about a character, in your mind, when you set down to create one? As soon as you started this character with parallel lives, are there just certain ways he had to develop?

Had to develop?

Okay, fair. Was more likely to develop?

I thought so. They all share certain things. An ability at sports, a love of music, they all share an interest in literature, film, art of all kinds. They’re all erotic beings, they care about that part of their lives—as most of us do. Nearly everyone I’ve known does. Some people more than others, I suppose. All given to a kind of inwardness. Those are what I would call the genetic traits—the nature-nurture debate, which is what you’re trying to goad me into talking about. On the other hand, having lived with these boys for so long, I tend to think about the differences.

Well, speaking of those, is there any degree of wish fulfillment in a novel like this? Like Ferguson 4 says, that god-like ability to be everywhere at once, even well beyond the normal abilities of a novelist to be wherever it is he wants to be?

That had never occurred to me. I guess you could say it’s the wish fulfillment of a writer who can tell it different ways. We’re always telling things one way, even when we’re making them up. I kept finding them, to be honest: the book is largely improvised. It just kept occurring to me as I was doing it, the feeling that I was finding material just hovering above the page on my desk. I’d plan certain things out, but they just never seemed to go that way on the page. I had many more characters and stories I wanted to deal with, and it always became much more streamlined than I thought it would be.

The things that happen in any given moment. That does make me wonder: you start the book with a joke, though it’s something like the foundational joke of the family. Without giving it away, is this sort of the ultimate response to the capriciousness of life—you just have to laugh about it?

Is that a joke? At times it feels like a joke. I don’t know why I began the book with that joke. I hadn’t heard it until about two years before I started writing the book. But I knew the tone, right from the beginning, which is why I started with the joke. I wanted it to have the feel of legend. According to family legend, he arrives in New York January 1, 1900, and supposedly walks on the street and buys a tomato, thinking it’s an apple. Since when do they sell tomatoes on the street in New York in January? It’s all a blur of conjecture, legend and myth. You have to understand the humour in all this, too. There’s a jocular sense of storytelling. Even the references of the gods, from time to time. It only seems like a realist novel. I think it seeks to break all the rules of how Americans write fiction. I’ve always been writing against them. I’ve never tried to join that club. I’m not in it. I don’t want to be. I don’t want to write the way people wrote 100 years ago. It’s getting tired.