By the time the guy from the Film Society at Lincoln Center steps up to the microphone to introduce the movie, as well as its writer and director (that would be Anna Karenina, Joe Wright, and Tom Stoppard) I’ve learned a great deal about the sixty-something woman sitting next to me. She thinks that Keira Knightley is a very good actress, the person sitting in front of her is too tall, she skipped the last Ben Affleck screening because she’s seen him on too many talk shows, and she has a sister in New Jersey who would have come but for the storm. She delivers all of this information to either me or the slightly more receptive young Asian man on the other side of her without waiting to hear our responses. And yes, she has the dropped-Rs, ancient tweedy jacket, and lack of indoor-voice of a stock Woody Allen character.

Her toss-off of that small fact—the storm—no doubt connects to our being on the Upper West Side. The Upper West Side is still the New York Allen promised you, big co-op buildings and Zabar’s and people lined up to see art films. It is also, now, a very rich neighborhood. And among its latest blessings is that it suffered little damage from the hurricane. Getting here was a surreal process, not least because it's the first time I’ve left the three blocks I live on in Queens since Sandy. By the time I came out on West 66th street I was elbowing my way through well-dressed, bag-heavy shoppers, enjoying a hurricane-induced day off. About forty blocks south, there is no power, and often no water. In Staten Island they’re still pulling bodies out of debris.

The disaster looming an hour’s walk from here goes unmentioned by the hosts or the distinguished guests, though their premiere was cancelled, earlier this week, on account of it. I suppose no one’s in the mood; it’s time for an escape on top of an escape. We might already be in a safe neighborhood, but it’s best to go to right back in time to Russia.

The film is a handsome creature, one of these things where the spectacle is worth the price of a ticket. People will love it for that alone: the sumptuous costumes, the way about half the movie literally occurs in a theatre, with the set pieces moving away behind the actors as they move through the various scenes. The transitions are things of seamless wonder. There’s a great deal of rhythm and dancing though no one fully commits to singing their lines, thank God.

But when the camera slows down the actors—who include the aforementioned Knightley and Jude Law but are otherwise mostly unfamiliar faces—often look like they’ve lost some kind of tune. Wright can create moving visuals, but his direction of the performers themselves often leaves something to be desired. Art direction is important; an emotional core can’t be sustained without the actors on board, though. For example, this Vronsky and this Anna have very little heat between them for adulterers who’ve given up everything to be together, and some terrible alchemy of Stoppard’s script and Knightley’s performance renders Anna a bit of a whiner by the end. Tolstoy was more sympathetic, as I recall, though it’s been awhile since I read the novel. In any event, Anna’s fate is more poignant if you’re not longing for an end to her hysterics.

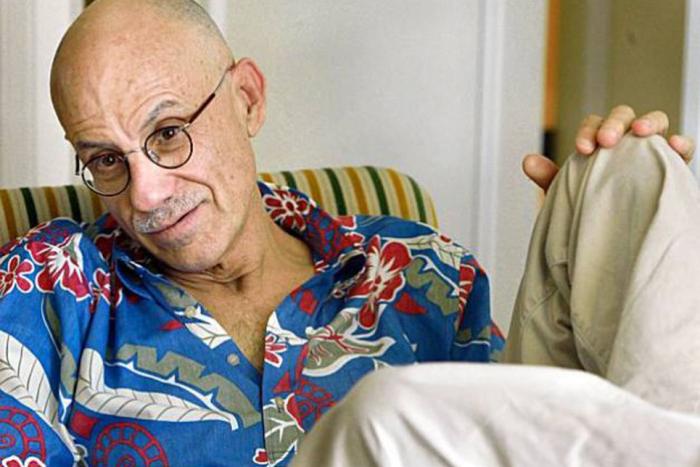

An explanation emerged when the distinguished-in-grey-suit-and-emerald-sweater-even-with-jowls Stoppard got up on stage with Wright. Though both had buttery accents, Wright had a stutter, and rather blunt vocabulary. He said he cast Knightley because he and she were “like siblings” and she was a “strong, powerful woman.” But I suppose anyone will look at a verbal disadvantage next to the mellifluous Stoppard. The playwright had nothing but praise for the director, to whom he kept, in his own words, “making love in public.” He loved, he said, how his director’s fluid approach had given the movie more “precious mind-time,” pulling audiences “through the transitions while maintaining belief in the internal lives of the characters.”

Both Stoppard and Wright talked directly of their desire to expanding the novel beyond the well-trod territory of Anna’s fall to adulterer. When reading the novel for purposes of the adaptation, Wright said he’d been surprised at how important the Levin character, who woos Vronsky’s jilted Kitty, was in the book. (Levin is sometimes minimized, or even cut altogether, from adaptations.) Wright pointed out, too, that Tolstoy himself spoke of Levin as his stand-in in the novel. According to Wright, Tolstoy kept a journal all his life except for the years he wrote Anna Karenina, and told people to look to that character specifically as a record of his mind in those years. And that he’d be willing to rename the book “An Interesting Family in 1870s Russia—though that’s not quite as catchy.”

That these two men would gravitate towards the inner life of a man in a story that is so famously about the inner life of a woman is... curious. And especially so considering how unsympathetic Anna looks on this expanded canvas. But no one asks about this. Instead we got an array of questions about why Wright decided to enclose some of the scenes in the theatre (“budget”) and which translations Stoppard used (the Constance Garnett, and the Pevear and Volokhonsky). Stoppard even says he used some of the dialogue more or less verbatim from the translations, though then he backpedals, a bit, saying that it’s not that he “punctilliously transcribed” it, but rather that he stuck to the spirit.

And then, when Wright and Stoppard were done and signing autographs, we filed out the door, and a woman nearby me got on the phone. “Well,” she said, “we’re out of the screening now. So tell me where to go. Tell me what I can do to help,” and then she hurried ahead of me down into the subway, which was only running as far south as 34th Street, just a few blocks north of where the lights stopped.