Imagine the ethicist’s standard drowning-child scenario: There they are, out in the water, and you must decide whom to save—two on one side, one on the other. Assume they’re small enough that you could save two at once, but that they’re far enough away and far enough gone that you only have time to swim out once. Whomever you don’t swim for first will drown. All else being equal, most people would decide to go for the greater good and save the two children. But what if the one child on his own was your son? What would you do?

I grew up in an age and in a place where “Christian” was the default description for good things and good people. Institutions with honorable or noble goals were said to have Christian values. When I used my allowance to buy candy for my friends, my mother would tell me that it was Christian of me. By adulthood, the model had changed: The synonym for goodness, once “Christian,” had become “family values,” and the famiy, as everybody knows, is the basic unit of virtue in our society.

Though many in the gay communities took issue with the original wielders of the term, they ultimately threw their weight behind it, making same-sex marriage their chief political cause of the last dozen years or so. But just as I eventually saw through the problems with associating everything nice with people who belonged to a particular religious genus, “family values,” too, struck me as a bit of a problem—and not just because of the subset of people who use the term to mean “that which is not faggoty.” Even when held up and touted by the most progressive unit out there, there is something inherent in family values as they are popularly understood that is profoundly anti-social, anti-community—something morally and ethically damaging to all concerned.

Which brings me back to those drowning children: If you choose your son over the two non-family members, that’s family values at work, forcing you to value a single member of your own bloodline over two members of someone else’s. Making any other choice, when you subscribe to family values, is very close to unthinkable—we may in fact be programmed against considering it. Family values dictate that, when our own family is at stake, we value the lesser good. They more or less force us to make the wrong ethical choice—indeed, they make us immoral.

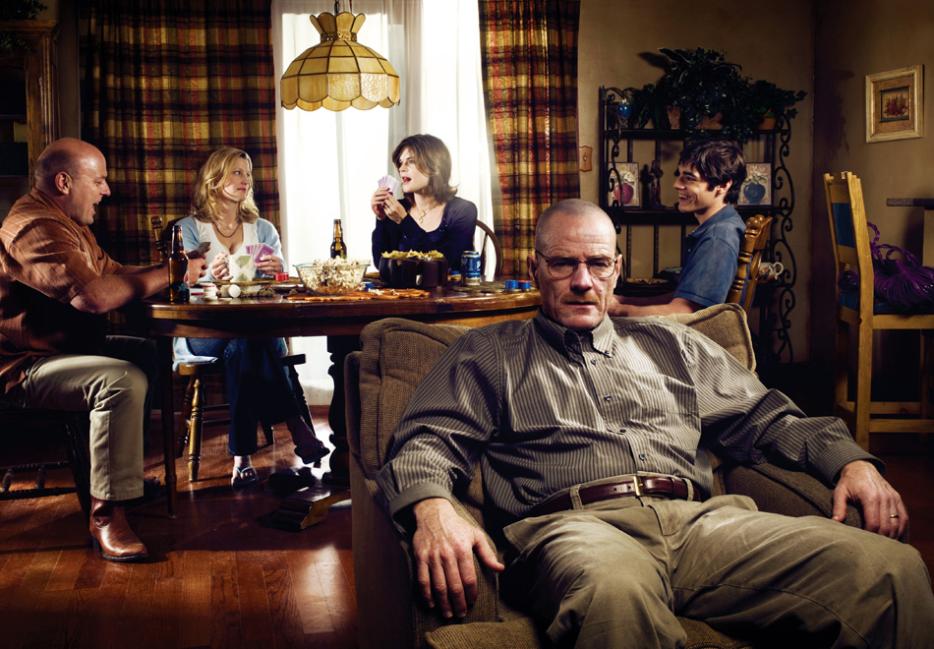

I was thinking about this recently when watching Breaking Bad, the story, as you’re likely aware, of Walter White, who as critical discussion would have it is either a good family man turned bad or a bad guy whose inner beast the building of a meth empire merely midwifed. For me, the show is actually a picture of a good family man in extremis: Though he does things that endanger his family, so did the caveman who left his family alone to get them food—that’s always been part of the deal. But look at how Walt’s behaved: Though he’s arguably closest emotionally to his occasional partner, Jesse, he allows Jesse’s girlfriend to die, puts him in all kinds of danger, lies to him when it’s not in Jesse’s best interest (unlike his lies to his family), and, now, seems to be getting closer to thinking about killing him.

And yet, even when Walt has thought his own death was imminent (even more imminent than his cancer diagnosis has made it throughout the show), he makes it clear that he wants his wife, Skyler, to keep the money his drug business has earned and pass it on to his kids. You could make the argument that Walt’s will to power overtakes his kinship bonds, but I think you’d be wrong. It’s clear, all the way through, that his concerns about family aren’t just rhetorical or self-serving: They’re the fundamental motivating factor behind all his evildoings, even more profound than the proximate cause, his notion of having been swindled out of his rightful patent millions by his erstwhile friend and former girlfriend. He may have imperial aspirations, but the main reason he wants to build his empire, patent or meth, is to give it to his kids, to be a good provider, to do right by his family.

Breaking Bad is an exaggeration, but it’s an exaggeration of something real and basic, something about which our thinking is as clouded as it was on the subject of what it meant to be a good Christian in the ’80s and before. To be clear, I’m not arguing against the importance of the family, nor its centrality to the continuation of this species of ours, of which I’m actually quite fond. But we do seem to have this notion that it’s an unmitigated good, an endeavor that is inarguably noble—holy, even. It’s not. It’s a deeply imperfect way to live life and build a society, one that is more appropriate to small, inter-related communities—in which the Venn diagram of self-interest and communal interest is basically a circle—than the gloriously complex worlds we actually live in.

I’m also not saying there’s a better way. Various regimes throughout history have tried to break down the family for one reason or another; you can read both the lines and between them in this piece to see the effect that’s had in the North Korean penal system, for one. North Korea, Germany, the Soviet Union and Romania were all pretty successful at convincing kids to value the state more highly than their families. It’s not that tough, it turns out, to use school systems and propaganda to place an eager little spy in every household. The results are horrific; I’m not suggesting we do anything like that. But perhaps we should try to move closer to understanding that, far from being a moral paradigm, we should be thinking of families in terms of harm reduction, as something more like a moral cancer—one of the central metaphors in Breaking Bad—that we have no choice but to live with and fight our way through.