A public figure’s final interview is not necessarily her best interview. In some cases it could be the most ordinary, unimpressive interview she’s ever given. She may not even know that death is imminent; or, if she does, if illness is lingering, her words might be products of it: panicky, delusional, bitter, beaten-down. None of this makes the words less meaningful, of course, and many people feel that language accretes a romantic potency as life inches away, until at the very end, with any luck, the survivors are left with some famous last words.

A few loved and liberally quoted of these include:

“I am perplexed. Satan get out,” —the occultist, Aleister Crowley.

“Tomorrow, I shall no longer be here,” —the prophet, Nostradamus

“LSD, 100 micrograms,” —the polymath, Aldous Huxley, whose wife administered a dose of the hallucinogen so he could hallucinate his way out of life.

These are punchy epitaphs, ready for Hollywood biopics. They neatly close the narrative of a person’s life, summing up their personality and the trajectory of their work in an economical language nugget.

We know about the three examples above because they were spoken by historical significants, and more specifically, by writers, those who chose to make meaningful language their life. These nuggets are perfect death fetishes—and what’s a more apt fetish container than a book, or better yet, a collection of books that looks nice up on a shelf? Melville House’s new series of Last Interview books attempt to capture death in language. The series includes volumes with Jacques Derrida, David Foster Wallace, Jorge Luis Borges, Kurt Vonnegut, and Roberto Bolaño, all writers whose work and life elicit enough fascination to warrant a close reading of their late conversations. Each book contains an author’s final interview, along with a handful of notable interviews from throughout their life.

Last words and last interviews are not the same thing, and yet we cherish both for the same reasons. The difference is a matter of degree: how close to death was the speaker? Final words have been collected in the sort of novelty, aphorism-packed books most commonly read on the toilet (e.g., Famous Last Words, Fond Farewells, Deathbed Diatribes, and Exclamations Upon Expiration, compiled by Ray Robinson). In 2008, Simon Critchley published an uncommonly thoughtful collection that broke the stigma of such death fetish books: The Book of Dead Philosopherswas an encyclopedia of all the text and ideas surrounding every well-known philosopher’s death (e.g., their final words, their written views on the subject of death/afterlife, the manner in which they died, and what their death precipitated). It’s an exciting collection that captures the history of philosophy through death.

Melville House’s Last Interview series seems to be less pointedly death-oriented. Unlike Critchley, who uses the words as a point of departure, the straight Q&A format that Melville uses carries no opinion or context with it. It is simply a documentation. In many instances, the interviews seem worthy of publication only because of the fatal events that followed. None are bad, but they might not be especially remarkable—which might be appropriate, since death is not always remarkable.

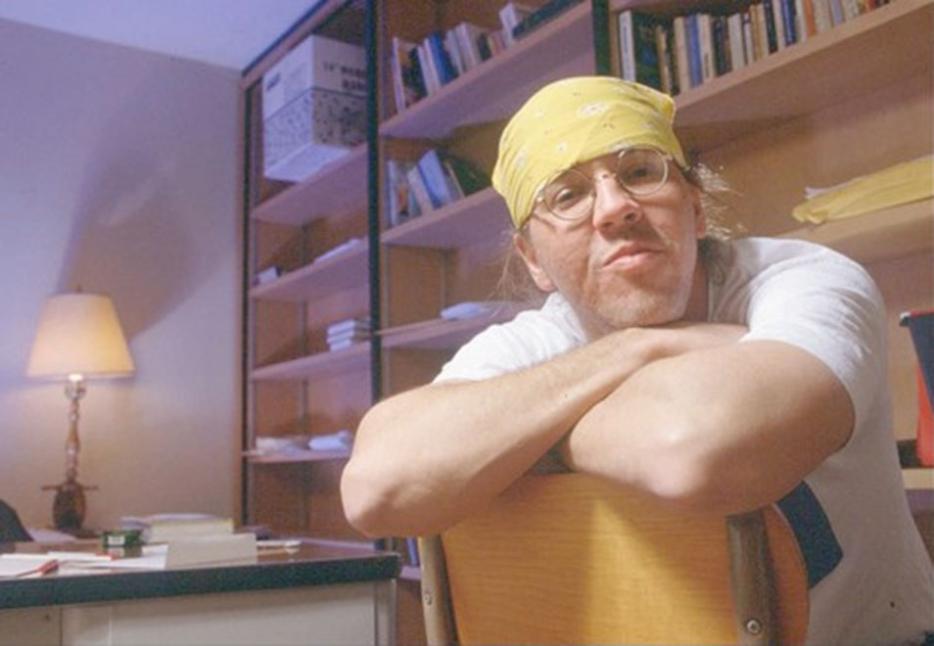

David Foster Wallace’s last interview, which was conducted five months before his death, is a short, uneventful Wall Street Journal Q&A on one of his lesser known, and more news-y books, a long nonfiction essay about the 2008 presidential campaign of John McCain. The interview ends with Wallace relating an anecdote about signing some copies of Infinite Jest with a cartoony face he liked to draw as a flourish. The final phrase is, “It always makes me smile to see that face,” which has a nice lilt to it, the sort of optimistic salutation that serves as a soothing salve on the wound of Wallace’s suicidal death not long after these words were published.

But what if Wallace hadn’t died? The same sentiment would have the punctuational weight of a gentle comma in the vast biography of Wallace’s life; but because of the circumstances that followed, these words are now the final period—at least, that’s how the series suggests you consider them. In some ways, the casual, tossed-off final remarks are fascinating. They slough off our romantic notions of death and carry a little sting of subversion. It’s as if the project is less interested in the text itself and more in the idea of the interview, a Kenny Goldsmithian conceptual curation of interviews, blind to content.

On the other end of the spectrum is philosopher Jacques Derrida, who knew he was dying from cancer and referred to the interview as his “obituary.” Derrida crafted his last interview purposely. His final words, published about two months before his death, read like the end of some grand French novel: “When I recall the happy moments, I bless them too, of course, at the same time as they propel me toward the thought of death, toward death, because all that has passed, come to an end…” ending on a suggestive ellipsis. A few paragraphs earlier, in that same answer, he states, “deconstruction is always on the side of yes, on the side of affirmation of life,” which is precisely the kind of neat statement that captures his entire life’s work, the influential field of semiotic analysis he helped to found in the ’60s. Derrida edited and approved the final draft, and did so knowing he was crafting the end of his biography.

The Derrida and Wallace interviews represent two different approaches to the interview, and yet, because of their context, they both have the feeling of a countdown to the final sentence. Of course, the recorded conversations might have petered out with cordial goodbyes and awkward niceties, but, as literature, the interviews never do. If an interview wanted to capture the true nature of death it could end mid-sentence, or with guilt and regret packed into its final statements, or at least with the complicated baggage that still clings to people when they die. But that’s not how readers like to look at the passage into death—we’d prefer a half-smile or a note of hopefulness. Vonnegut’s last words are tidy in this way, resonating with the same tone as his bittersweet, colloquial prose: “I’m enormously influenced by the sermon on the Mount,” he says, “But I gotta go. I’m not well. Good luck.”

All of these interviews seem to carry the same tonal ending, a cadence that feels false. For instance, I don’t believe I, or anyone I’ve ever known, has ended a conversation with a quote, especially not one from the Chilean naval officer Arturo Prat: “While I am still alive, this flag will not come down.” But this is how the Bolaño interview putatively ended.

We can devour tangy obits dozens at a time in a book like Famous Last Words, feeling their impact the way we would a subtle joke. There’s nothing wrong with that, and I hope people continue to die aphoristically, because I enjoy reading these words, and they translate well to literature. But we also have to be willing to read the real, awkward, half-uttered, conflicted, drooling language of death, without the editing.