"Books weren’t much use, aside from a few novels, and who can trust a novelist?" - Harry Mathews, My Life in CIA

"All writers are spies." - Timothy Garton Ash

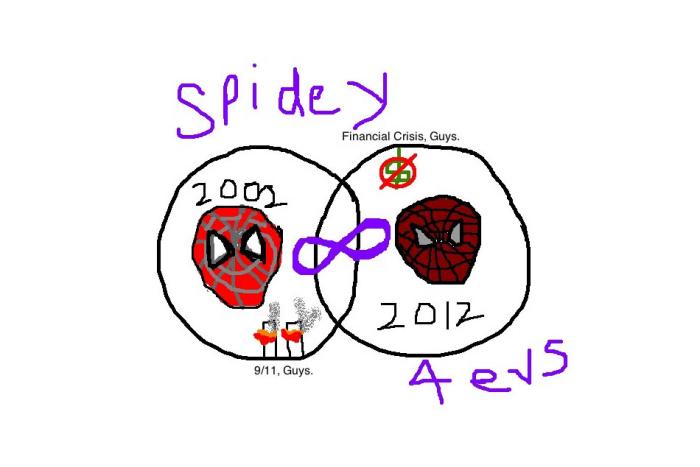

If, as some would have it, everything—memory, identity, perception—is fiction, then spy fiction, in particular, is the genre that repeatedly demands: Don’t believe everything you see, hear, or read. And don’t believe everything you say or write, either.

Spy fiction insists that everything, life, is also constant, unrelieved gamesmanship, impersonation, deception and misdirection. This is the animating principle in Ian McEwan’s latest novel, Sweet Tooth, simultaneously about the historical intersection of literature and espionage, a semi-autobiographical mash-up, and itself a kind of abstract, attenuated spy thriller. The parts fit together as precisely and improbably as the components of an improvised explosive device.

Sweet Tooth’s plot is simple (deceptively, of course): in London in 1972, an attractive young woman named Serena Frome (“rhymes with plume”) is recruited by the intelligence agency MI5. The Cold War has not cooled, and to shape and dictate the cultural and ideological conversation, the agency is secretly bankrolling writers whose politics align with the anti-communist government of the day. Serena, long a lover of literature both lowbrow (Valley of the Dolls) and highfalutin (One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich), is enlisted in an operation codenamed Sweet Tooth, and tasked with “encouraging” an up-and-coming novelist named Tom Haley. Frome, delighted with the job and then later by the man and his work, is soon engulfed in a world of shifting allegiances, romantic intrigue and self-conscious (and self-annulling) literary conceit. To tweak a phrase, she’s a spy in the funhouse of love. If all writers are spies, then all spies, in some shape or form, are writers.

McEwan’s nostalgic novel is strewn with references to his own biography and oeuvre, but the subterranean, now almost forgotten, history that underpins Sweet Tooth is as riveting and dramatic as anything the novelist could dream up. Mainly because that history was dreamed into being by novelists (and poets, and playwrights, and journalists), and the politicians and spooks who loved them. Espionage and Anglo-American literature’s entwinement goes way back—bad boy Elizabethan dramatist Christopher Marlowe was reputedly a government spy—and World War II, then the Cold War, only made this relationship cozier.

With the end of World War II, and the UK, USSR and US no longer uneasy allies, the competition for hearts and minds—and in particular, the greatest creative minds of the period—became pitched. Modern warfare has always required propaganda. But the notion that propaganda could be deployed more subtly, insidiously, and effectively—that propaganda could be grey rather than white (acknowledged, open) or black (outright fiction and lies)—resulted in a relentless culture war, with all sides organizing lavish international conferences, music festivals and art exhibits, trotting out musical and literary stars (the Soviets paraded Shostakovich and the Bolshoi, the Americans and the CIA, completely covertly, had the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Gary Cooper and Tennessee Williams) as exemplars of artistic and philosophic superiority. If communism was not always specifically denounced, Anglo-American democratic values were advocated. The rhetorical sabre-rattling was deafening, the race to capitalize Truth as fervent as the race to the moon.

In the U.K. in 1948, Labour MP Christopher Mayhew established the top-secret Information Research Department, a division of the British Foreign Office, as a Soviet propaganda counteroffensive. Its work largely consisted of subtly (and not so subtly) manipulating BBC journalists, and subsidizing anti-communist magazines and publishing houses with funds funneled from the so-called Secret Vote, a Parliamentary allocation of money for secret services.

Arthur Koestler, ex-Communist Party member and author of the anti-totalitarian Darkness At Noon, persuaded the IRD to publish a series of cheap, non-communist but left-leaning books. Partnering with a likeminded small press, the IRD launched Background Books, and released titles like Bertrand Russell’s Why Communism Must Fail. The IRD had even more success distributing and translating independently produced work like Czeslaw Milosz’s The Captive Mind, and more notoriously, George Orwell’s 1984 and Animal Farm, saturating the entire globe with Orwell’s anti-Stalinist allegories.

Orwell was an early supporter of the IRD and a friend of Koestler’s, and just before his death in 1950, he gave the department a list of 38 supposed Soviet sympathizers (divided into “crypto-communists, fellow-travellers” and untrustworthy propagandists, the names included Charlie Chaplin, Michael Redgrave and J.B. Priestley). Kept under wraps for half-a-century, the list’s public unveiling in 1996 was explosive—the left-wing icon was accused of being a little Big Brother himself. But as Timothy Garton Ash has pointed out, the ramifications for those named were mostly minor—they simply were not asked to contribute to the IRD. And the vast majority of those continued to pursue very successful careers, even when a few were later unmasked as actual Soviet agents. Redgrave, for his part, played General O’Connor in the 1956 adaptation of 1984.

The first translations of 1984 were serialized in the German-language publication Der Monat (The Month), founded and edited by Melvin Lasky. Lasky was an American intellectual and journalist, a decidedly anti-communist progressive, and Der Monat was a journal conceived as “a voice for Western ideals,” sponsored by the American occupation government. Aside from Orwell and Koestler, its contributors included Hannah Arendt, Thomas Mann and Saul Bellow.

Lasky was a key figure, involved with the organization of the first Congress for Cultural Freedom in Berlin, and then later, for ten years, as editor of Encounter, the British cultural journal co-founded by the poet Stephen Spender and neocon godfather Irving Kristol. Encounter was essentially free to publish what it wanted—and it published the pantheon, from Nabokov to Auden to Borges—as long as its articles and stories did not explicitly criticize, or adversely affect, American interests. In all cases, Lasky was supposedly unaware that these ventures were largely funded, indirectly and clandestinely, by the CIA. The moneymen hid their tracks, but they spent a lot of money. In addition to subsidizing Encounter and European tours for the Boston Symphony, it produced an animated film version of Animal Farm, and helped prop up faltering litmags like the Kenyon Review. Lasky would later say he believed Encounter received its money from private American foundations, but when the New York Times broke the scandalous CIA news in 1967, Spender resigned in outrage while Lasky defiantly stayed on. (The intelligence agency had officially stopped funding the magazine the year prior and it finally folded in 1991.)

If Spender and others were unwitting dupes, then others, like the American novelist and nature writer Peter Matthiessen, entered into such relationships with their eyes wide open. Matthiesen was recruited by the CIA when he was a student at Yale in 1950, and used The Paris Review, the magazine that he co-founded with George Plimpton and others, as a cover for his intelligence-gathering activities. “I spent my days deceiving people,” he said.

When this was publicly revealed many years later, Matthiesen discounted the significance of his adventure. In an interview with the New York Times, he characterized the agency in this pre-black ops period as a somewhat more innocent institution, and his own involvement as little more than a way to get a free trip to Paris to write his novel. He insisted that the CIA had never directly interfered with, or manipulated, the editorial direction of the journal.

A controversial but inconclusive Salon story, published in May, suggested that the Review’s connections to the CIA exceeded Matthiesen’s editorial tenure and that it had numerous ties to the Congress for Cultural Freedom, which provided financial support and publicity even as other comparable American publications that criticized the Cold War were put under surveillance. (When McEwan’s Serena Frome is first being briefed on Tom Haley, she learns he’s placed short stories in, among other publications, The Paris Review.) Matthiesen’s espionage career was short-lived and uneventful, however; he claimed to have resigned as soon as he realized his politics were a bit pinker than the agency’s.

There’s something almost quaint about all this history. For one, it’s almost impossible to imagine a time when writers would have been thought so supremely influential, so much so that governments expended so much time, effort and money to court them, openly and in secret. Back then, writers were magnetic, magic, mountains. Now, in our topsy-turvy era of plagiarists and hacks, where books are only as big and bright as nightlights, what writers command, in the eyes of political leaders, such respect, wield such power? It’s equally as impossible to imagine a geopolitics so black-and-white. All wars are, in some way, cultural, and the gloomy War on Terror explicitly, relentlessly, so. But it’s a culture war that takes place, as far as the general public is concerned, largely on Twitter and TV, not in the puny pages of poetry journals. Words are still power, of course, but words are not enough.

Maybe, though, Christopher Hitchens’ undying support of the Iraq War was some kind of Bush-league buy off? One can easily imagine Hitch as a spook, wreathed in smoke, wrapped in a Mackintosh. Or maybe Martin Amis, another of McEwan’s pals (he has a walk-on in Sweet Tooth), wrote his witheringly anti-Stalinist Koba the Dread as an elaborate cover, in order to foment anti-capitalist conspiracies? Whose payroll is Orhan Pamuk on? David Grossman? When will Stephanie Meyer and Mitt Romney’s diabolical Mormon compact be exposed? And are not books written, to paraphrase Nietzsche, to hide what is in us?

Don’t believe everything you read.