The more we learned about Craig Stephen Hicks, the man behind the recent murder of three young Muslims in Chapel Hill, the less the story became, in some ways, simply about a specific tragedy, and more about Hicks’s beliefs—or lack thereof.

The fact that Hicks is a self-described “anti-theist” who has published Facebook posts denouncing religion was, according to some, reason for atheists to do some self-reflection. In The New Republic, Elizabeth Stoker Bruenig argued that the murders should act as a wake-up call for a movement that is “more critical of religion than introspective about its own moral commitments.” Atheism, Bruenig argued, is “philosophically bankrupt and evidently blind to its similarities to the religions it derides.” It was easy to see Hicks as the embodiment of a particular kind of atheist: white, male, and very angry.

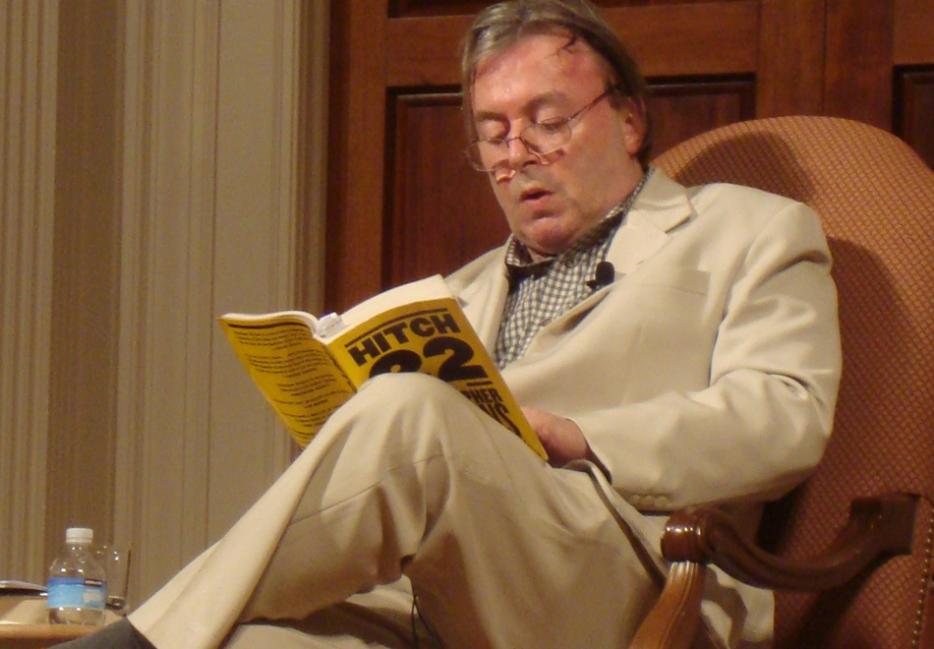

The idea of the “angry atheist” is a pervasive one. Along with “militant,” it’s the adjective most often appended to people like Bill Maher or Richard Dawkins (the author of The God Delusion,who seems determined to replace his legacy as a brilliant evolutionary biologist with one as “guy who’s kind of a dick on Twitter”). In survey after survey, Americans see non-believers as untrustworthy and immoral. One study found that 48 percent of Americans would disapprove if their child married an atheist.

In an article in an upcoming issue of The Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied, a group of American psychologists examine what they call “the myth of the angry atheist.” Do people actually think all atheists are furious, or does it just feel that way? And, if the stereotype exists, is there any validity to it?

To test the pervasiveness of the stereotype, the researchers first asked people to rate theists and atheists on a scale of 1 to 7, from “not at all angry” to “very angry.” Respondents believed that atheists were significantly angrier than people who believed in God.

The psychologists then tested unconscious bias using an implicit association test, a common tool in psychology. Participants were asked to press one button when either the word “atheist” or a word related to anger appeared on the screen, and to press another whenever they saw “believer” or a calm word. They then switched the associations, matching “atheist” with calm words and “believer” with angry words, and measured how quickly people were able to sort words into the correct categories. If it takes you a little longer to consciously sort “atheist” with “easygoing,” it’s because you implicitly feel that the two don’t naturally belong together. The researchers found people were more likely to associate anger with atheism than with calmness.

Next, to test whether there was any validity to the stereotype, the researchers recruited over a thousand students, had them list their religious affiliation, and then attempted to measure their anger levels on a commonly used scale (answering questions such as, “I have trouble controlling my temper” on a scale of 1 to 5). For theists and non-believers alike, the results were nearly identical. They did three other studies, testing believers and atheists on different anger scales, manipulating their anger by having them write about a rage-inducing incident from the past. In each case, they found no significant difference. “Our results suggest that the idea of the angry-atheist is a myth,” the authors write.

As an even-keeled atheist, this doesn’t particularly surprise me. I’ve only ever greeted the absence of a god with placid equanimity. Not once have I been tempted to yell at a server or write a needlessly cruel Internet comment, content in the knowledge that there’s no hell for me to go to. The idea that the unbelievers I know—the middle-aged Chinese-Canadians, the lapsed Catholics and secular Jews—might somehow be inherently angry just seems silly: as nonsensical as the notion that individuals who belong to a specific religion might be specifically hateful.

But while the study’s results aren’t surprising, its tone also seems to exemplify so much that people find unpleasant about a particular strain of atheism.

“Typically, overt discrimination or unjustifiable negative behavior toward minorities is not explicitly tolerated in many societies (e.g., in regards to race or gender),” the authors write. “However, discrimination against atheists appears to be somewhat acceptable.” They conclude by urging readers to intervene next time they hear someone spreading the myth of the angry atheist: “We would encourage people to challenge this idea when expressed by communication partners or when encountered in popular media sources. It is a misperception that should be corrected rather than endorsed.”

Atheists are, of course, a minority (in the U.S. much more than in Canada), but using the language of discrimination to describe a group of people who are, statistically speaking, young, white, and well-educated, feels disingenuous. And the idea of definitively disproving the anger of atheists by using a series of studies has a tinge of the presumption of those “watch this person dismantle the concept of god!” videos. It’s an attitude that eschews nuance in favour of belligerence, and equates “reason” with an allegiance to a particular set of facts.

Because, while the authors are right to point out that self-described atheists aren’t any more likely to fly off the handle than Hindus or Christians, it’s possible that “angry” is an imperfect short-hand for another set of characteristics that seems to have defined one prominent segment of the current atheist movement—a sort of condescending superiority and a feeling of victimization, an unwillingness to address the misogyny in the movement, and an aggressiveness on the Internet.

Atheists aren’t angrier than anyone else—that much is clear. But if your response to the stereotype is to ignore criticism and instead email someone a psychological study proving that atheists aren’t angry, you might be part of the problem.