I first saw Fancy Feast perform around 2012 in Brooklyn at the body positive queer dance party Rebel Cupcake. My memories of this are admittedly a little, well, whiskey- and refined sugar-tinged, but she corroborates this would have been around the time she started her burlesque career. I had just moved to New York and as I watched juicy babes go-go and roller-skate and lip-synch their way through their raunchy routines in the middle of the sticky dance floor, I remember thinking, “This is exactly what I want to get from and give to this city.”

Over a decade later, Fancy Feast is one of New York’s most beloved and transgressive nightlife acts, boasting accolades like Miss Coney Island 2016 and the Revolutionary Award from the 2017 New York Burlesque Festival. She is also a venerable producer of the Fuck You Revue (a monthly variety show featuring themes like ShAmerica, Beastmode, and Jewtopia), and the Unbookables (“too niche, too weird, too messy, too wtf”), as well as a pleasure-product saleswoman, sex worker, and licensed therapist.

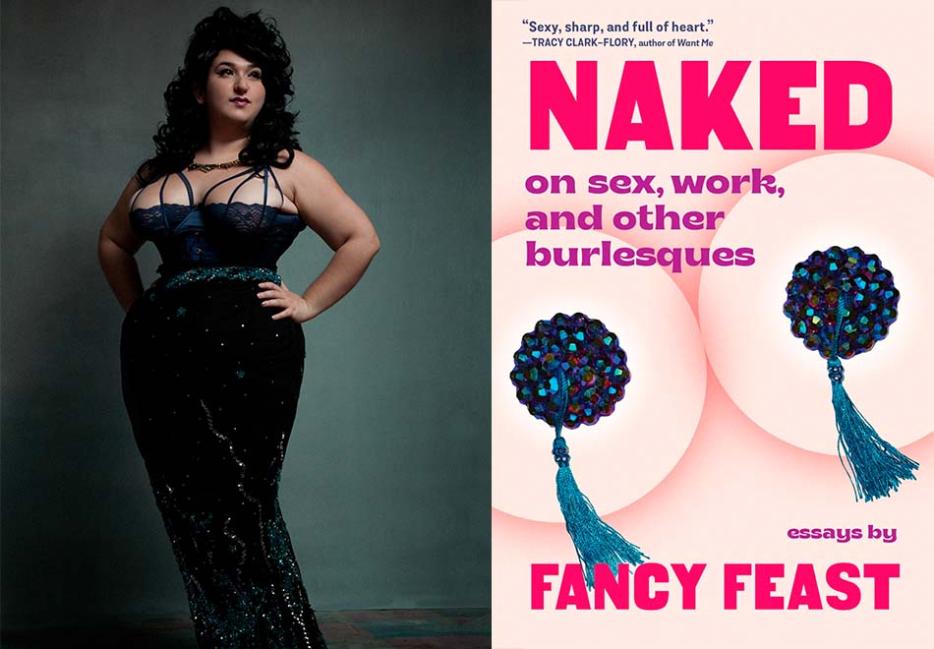

Fancy may be a multi-hyphenate, but at heart she is a Mistress of Ceremonies. With Naked: On Sex, Work, and Other Burlesques (Algonquin Books), Fancy has brought her singular voice to the page, and every essay is indeed a ceremony. In her first book, form follows function, in the sense that it’s a voluptuously voice-y book about life onstage, often with informal and irreverent asides to the reader (“let me assure you”). Reading her words puts you right in that rickety chair in a seedy dive bar, nursing your own whiskey; you catch your breath as Fancy grabs the microphone and directs the spotlight to her wonderful community of provocateurs. You know you’re going to be entertained and unsettled until you stumble out into the night, hot under your collar, the impressions of bouncing flesh and sequin flash still shimmering in your eyes.

But Fancy is not simply a stage presence adapting her routine to a book. Although she is full of bon mots, they enhance her prose style rather than distract from it. The more personal her stories get, the more lyrical she allows herself to be.

Her essays are very smartly themed, taking us from her struggles with PCOS (which she calls “wrong puberty”), to correcting customer etiquette at a Lower East Side sex shop, to “walkaround gigs” at upscale sex parties, to making her own costumes, to working as a phone sex operator during COVID quarantine to Rikers during social work school. More than anything, this is the skillful self-portrait of a quintessential twenty-first century New Yorker blending labour and pleasure: creative, scrappy, and in her words, “negotiating the coexistence of all my selves.”

I caught up with Fancy over email in June. She was in New York and I was in Los Angeles.

Tina Horn: What do you feel creatively and thematically unifies these essays?

Fancy Feast: Projection, performance, and subjectivity. More than work, or sex, or show business, I think these essays are about the tension between the desire to be objectified and the drive to be subjectified. But like, I am banking on the probability that more people want to read about tits than object relations, so it’s a blend.

There’s a scene in the chapter “Work Nights” where you describe an audience member approaching your colleague to say, “I really liked your act. But do you know what would make it better?” No one, as you elucidate, wants to hear this in the context [should this be “in that context”?] (especially when the suggestion is to do something painfully obvious like set a BDSM act to “Closer” by Nine Inch Nails). Do you think there’s something about our social construction of art, broadly, and performance art specifically that leads people to believe once you’ve made yourself creatively vulnerable, you’re fair game for critique from entitled randos?

I think art, particularly art that is embodied when performed, or requires the presence and proximity of the artist and the viewers, creates tension around stimulus/response that needs to be resolved. It’s less satisfying to have a feeling when there’s nowhere to put it or nothing to do with it, and so when the person or experience that generated that feeling is right in front of you, your desire is to give the emotional response right back. Kind of a feelings-first hot potato.

For me, the big difference is that hopefully, the performer or artist has put a lot of time and care into the message that is being broadcast, including thought about how it might be received and what is intended, whereas the responses may range from deeply connected and generous to scattershot, rude, or unwelcome. I’ve received criticism from randos for just existing in the world, just walking around outside and trying to do my day, so I don’t think it’s unique to art making. But I do think art opens a door to a kind of connection that people crave, and we are unpracticed and clumsy about how to do that thoughtfully.

You write that “it would be a mistake to believe that New York City has gentrified away the gritty glee...” Do you see your book in a lineage of documenting NYC underground art from the inside?

I wrote the vast majority of this book during the pandemic, at a time when I was not sure if nightlife and live performance would ever come back in the same way. NYC was disinterested in bailing out adult performance artists and the venues that book them, and many of the bars and theatres I perform in were clinging onto solvency. So when I wrote about performing, I was not sure if I was writing a eulogy for a time and place that was about to be gone forever.

Yes and no, as it turns out. A ton of performers in the generation before me have retired, and many of my contemporaries moved away or chose new professions. We were all forced to pivot and so we are moving in those divergent directions. I think nostalgia can be a trap but hey, it’s all over the book. Maybe that’s unavoidable.

How does it feel to reach a stage of archiving a culture as you make it?

Nearly all of my gigs for the past twelve years took place without professional documentation, without photos beyond backstage mirror selfies and blurry phone shots from people in the crowd who don’t remember our stage names. Almost all of my performance work exists in memory. So there’s something to be said for preserving artifacts and stringing recollection into narrative. I’m certainly standing on the shoulders of people who have shaped NYC’s downtown culture and lived long enough to write about it. I pored over my copy of Please Kill Me as a teen. My most enduring celebrity crush is Anthony Bourdain. The movie Shortbus was all the convincing I needed to move to NYC. I eat that shit up. To be even glancingly in conversation with those cultural touchstones of mine is thrilling and feels like a tremendous responsibility.

You declare that filth is both humanizing and nutritious. Who were some of the writers, filmmakers, and performance artists who contributed to your idea of filth?

I could really go and go. Annabel Chong, who blurred the boundary between porn and performance art, and whose (at the time) record-breaking gangbang was inspired by the Roman empress Messalina. Nina Arsenault, an artist, academic, and sex worker whose writing and visual art foregrounds bodily agency, the abject, and the divine in an unparalleled way. Mark Aguhar and her contemporaries on Tumblr in the early 2010s who produced digital records of desire and rage that shook me to my core. Mollena Williams-Haas, a writer and sex educator whose work about the human imperative of integrating our less palatable desires is a place I return to often. I like writing that is sexy, gross, and visceral: Carmen Maria Machado, Gretchen Felker-Martin, Clive Barker, and problematic though he is, Roald Dahl are favorites of mine. And then, I don’t know how a list about filth could not include John Waters.

Tell us more about how filth is socially constructed and why you believe it’s good for us?

Not to be a total Jungian about this, but I believe in his theory that everything that we do not consciously acknowledge about ourselves is punted into a place he calls the shadow. Our weaknesses, our desires, our impulses all play in that space. In order to be whole, we must render that part of us conscious and integrate it. We must allow the hungrier, weaker parts of ourselves to be part of our growing edge. Body fascism, sex panic, transphobia are all, among other things, attempts to keep the shadow inhibited. These forces are so destructive—of personhood, of community, of society. But they are all forms of control, which puritanism requires. I think puritanism is a force of evil and needs to be upended and done away with. Filth, pleasure, obscenity, and embodied expression is one tool to chip away at it.

You tell the story about horrible interpersonal assault and institutional mistreatment in film school. Do you ever see yourself reclaiming the medium of film, and if so, what would you make a movie about?

Would I accept a development deal? You’re goddamn right I would. Oh, that’s not what you asked?

When I make it big in surely soon-to-be utopian Hollywood where writers’ labour demands are met and we are treated like the kings we are, you’re at the top of my list of freaks to coronate.

I’m currently working on my second book, a novel about a Jewish family in a haunted house, and it started as a screenplay idea. Basically, I wondered what I would do if I needed an exorcism. Would I, as a Jewish person, call a priest? Use holy water and a crucifix? The idea of how to work within systems that weren’t designed with you in mind is a compelling one for me, and one that’s well-suited to the horror genre. So that’s where I am going next. I think the premise lends itself well to a reasonably low-budget film and even thinking about that feels illicit somehow.

Let’s talk about this concept of tikkun olam: how does ritual performance art repair the world and improve society?

Sometimes it doesn’t. Sometimes it does. Ritual performance art, as you put it, provides a space for catharsis and cathexis: for the satisfying relief of intense emotion and for the concentration of energy and abstract concepts into a single concrete object: the performer. Those two experiences, especially when they happen simultaneously, can be life-altering for a performer or for an audience member. I know that performing has saved my life, and I have heard the same for viewers and artists alike. Representation that goes beyond a corporate check box, witnessing people who look like you or look very different from you author their own possibility and present themselves and their ideas in a thorough, unflinching way, and having a community respond to it and receive it with joy, is that good shit. It makes the impossible possible.

That said, sometimes the thing that feels the most good does not do the most good. I used to write court mitigation to get people released from Rikers. It felt like the most tangible good I could do in the world, but it was frustrating, time-consuming, and no one applauded when it worked, nor was I ever actually there to celebrate my clients’ release. Writing those memos did something that, in my opinion, accomplished more than I ever have as a performer. But it left me feeling depleted and angry at the criminal justice system. So I think there always needs to be a blend, some mix of things that do more immediate good but don’t feel warm and delicious, and things that provide fuzzy feelings that also hopefully sow the seeds for goodness down the line. And importantly, the ability to discern one from the other.

You have a chapter on working as a phone sex operator in deep quarantine, where you took your raunchy performance skills and knowledge from working as an educator in a sex toy shop, channeling them into professional fantasy and dirty talk. You also tell the story of a connection you made with a client. This was really bold of you to air what some sex workers consider to be our dirty laundry, as that professional boundary is something that so many clients push if they believe it’s possible to cross it. Then again, you’re collapsing the happy hooker versus damaged goods binary, complicating it with real human emotion during a time that was generation-definingly vulnerable for all of us. Why was this an important aspect of your phone sex story?

I’m so glad you asked about this, because that chapter is where I feel the most discomfort writing about my experience in a forum that (I hope!) will be widely consumed. I feel a sense of responsibility towards the many sex workers who I love and who I am in community with, to conduct myself and tell stories in a way that takes their safety and well-being to heart. So much narrativizing about the sex industry happens in a way that erases the workers themselves, whether through rescue narratives and infantilization, stigmatization and disenfranchisement, or even by bludgeoning folks with the idea that sex work needs to be fun and empowering in order to be considered valid work. None of these narratives permit the humanity of individuals working within this industry. None of these narratives acknowledge the piss poor social forces of labour and capitalism more broadly that create and reinforce harmful working conditions and deepen social inequality between sex workers and beyond.

The essay is placed intentionally where it is in the book. It could only exist after I discussed the way my unearned privilege has fundamentally shaped my relative safety and choices in the opening essay, “The Assorted Nudities,” the pain I feel around my own projections and fantasies in “Doing Yourself,” and the need for shattering illusions around the empowering nature of labour in “FAQ” and “Mistress of Ceremonies.” I can’t imagine that it will read like a how-to guide to turning a provider into a girlfriend, or that it’ll come across as a screed for “why sex work is always great and everyone should do it.” Even so, I conducted my edits with the awareness of those possible outcomes because there is a dearth of complex representation of sex work, and those are easier buckets to toss things into.

My relationship to this client arose during a profoundly lonely, emotionally desolate time. We both struggled with the limitations of our roles, and with the performance of authenticity and then, terrifyingly, the real thing. It was that vulnerability and humanity that I am more interested in, and why I believe the story merited inclusion in the book.

What are your hopes for the future of sex ed and pleasure-product spaces?

I could really do with the end of the white, thin, cis, girl-bossification of sex ed and pleasure-product spaces. I’d like more sex shops and sex toy companies to unionize. I’d like more fat and trans people represented in all areas of the industry, not just used as occasional lip service in advertising. I’d love for product development to be possible without relying on venture capitalist money or exploitative factory worker wages.

What are your hopes for the future of burlesque?

I hope the future of burlesque is that it has one. I hope there will be more spaces that foster risk-taking and creativity while holding artists accountable for the choices they make. I hope it pays better across the board. I hope there will be more Black and brown performers who are featured and celebrated. I hope burlesque doesn’t get sidelined by venues because there’s a TV show that makes some drag queens famous, but no corollary exists for us. I hope audiences continue to experience how special and singular it is. I hope audiences keep tipping in cash.