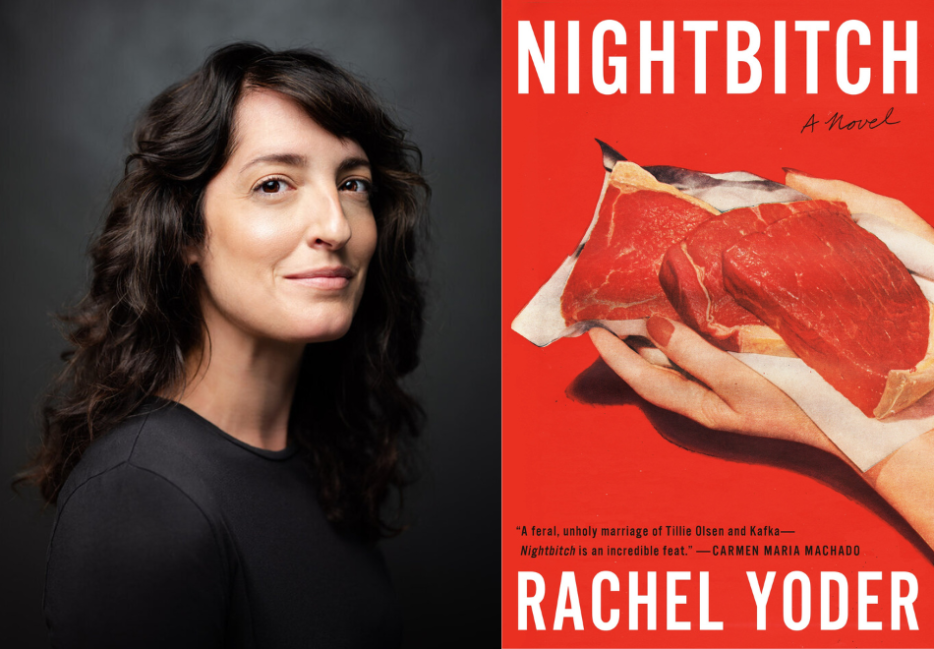

Inside you, it is said, there are two wolves—one of whom is insatiably hungry for meat. At least that is true of Nightbitch, the hilarious, newly feral central figure of Rachel Yoder’s 2021 debut novel, Nightbitch, just released in softcover (Vintage Canada).

At the novel’s opening, our eponymous bitch is deep in her flop era. Once a promising artist, she has ceased to be productive due to motherhood; her creativity is hampered by a lack of sleep, personal space, and adult conversation. Nightbitch’s main source of engagement is with her two-year-old son, in which Yoder captures the delight, tedium, and mild-to-spicy psychosis of spending all your time with a barely verbal agent of chaos.

Mentally fixated on the banal freedoms experienced by her on-the-road husband and pursued by a gregarious blonde mom (who is either trying to draw her into a multi-level marketing scheme or an herb-centric cult), Nightbitch’s body begins to…change. Her teeth sharpen. Unusual hair grows. A tail emerges at the base of her spine, along with the desire to wag it. At first, this troubles her. Then it cues an after-hours world of lupine delight.

Yoder anchors Nightbitch’s fantastic universe in bodies of flesh and myth, communicating the protagonist’s new power, impulses, and violence with visceral joy. With its cinematic imagery and rich characters, Nightbitch is already being adapted for the screen by Marielle Heller and will be starring Amy Adams in the title role.

Last summer, I spoke with Yoder via a Zoom call from home in Iowa City (her own son was in the kitchen making brownies with his grandmother). Eloquent in speech as in writing, Yoder has an endearing habit of leaning toward her camera when reaching the pinnacle of a thought.

Naomi Skwarna: I recently read the essay you wrote in Lithub about dealing with chronic pain and illness. It seemed of a piece with Nightbitch, which is such an embodied novel. How did you tap into that palpable feeling of becoming a dog-wolf-human character?

Rachel Yoder: I think if I have any superpower, it’s probably feeling everything very much. It’s both a superpower and a burden. I’m very sensitive emotionally, and my emotions are closely tied to physical sensations. They’re not disembodied ideas of emotions; emotions have their weight in my body. For instance, it’s hard for me to watch really emotional movies because it feels like work to get through them, and that’s not enjoyable for me. Before I started writing Nightbitch, I’d been having a lot of feelings for two years, and they were trapped in my body. It’s really hard to be incredibly angry and incredibly sad, and to have those sensations in your body and not be able to move through them, not be able to transform them in some way.

We have all this language for talking about feeling stuck. I’ve been going to therapy on and off for many years, and therapists would say you have to move through that. What I’m realizing is that that’s a very actual, physical directive. It’s not a figurative way of talking about it, but literally: how can I take the anger and get it moving in my body, from my chest to another place, out of my body? You start to think about howling and screaming as a way to move anger, and it’s very effective. Man, I wish that were more socially acceptable! The closest approximation I have for that is writing to move stuff through my body. It’s been that way from when I first started writing. Everyone writes for their own reasons, but I need a way of taking what I’m feeling and moving it because it’s too much to hold in my body. And it does make me sick if I don’t move it. Nightbitch felt really good to write because as you can probably tell from what you’ve read, it was just rage sort of pouring onto the page. I was finally able to get it out of my body. The whole book was a practice in doing that, to a certain extent.

It’s very cathartic to read. What is it about a toddler-aged child that cues the Nightbitch—both the character and the novel?

My son was three when I wrote this. When he was zero to one, I was so happy every moment of every day. I was basically getting high off my baby, holding him for hours and staring at his face. By the time he was three, I’d been home long enough, doing the stay-at-home mom thing, and we’d formed this intense bond. When kids are that young, and really with just one caregiver for most of the week, it’s a very intense relationship. By the age of three, he was very verbal, very demanding as three-year-olds are, and very bonded to me. That was really hard, because it’s an intensity I’d never experienced before—of not only being responsible for someone else, but him literally telling me what to look at, like, no, Mama! Look here! It was very intense, [my son] trying to take ownership of my entire existence. That felt like the tipping point, and a transition needed to happen. The transition was: mother needs to start writing, and you need to start going to daycare a couple hours a day—which was, y’know, a huge tragedy in his little life.

Not to project too much autobiography, but in the book, Nightbitch experiences a kind of feral rebirth as a mother, simultaneously becoming a more radical version of the artist she was previously. And so I was wondering: is Nightbitch also about writing the book Nightbitch?

The short answer is yes. I had a really bizarre experience of finishing it, writing that final scene, and then just sitting there in a sort of fugue state. I tweeted something like, “The thing about writing a novel is that the process of it makes you the sort of person you need to be to write it.” You know what I mean? Like, you’re not only writing the novel, it’s writing you, and you’re turning into the person that you need to be to write it.

That felt true for this book. So much of it was about Nightbitch being authentic and finding her voice. I needed to do that—I needed her to show me how to be authentic, how to be honest. The entire book was an exercise in that.

I’ve never heard of writing a book described like that before. It’s a little bit sad though, because you only become that person when you get to the end of it.

[Nods in assent]

Did you ever have any concern about how some of the Nightbitch’s violence might be interpreted?

I might have worried for a minute. But I’ve been—and I don’t quite really understand how or why—somewhat Zen about the book, and that I don’t have any control over how people are going to read it. It’s a weird book. Some people are not going to get it, and/or hate it. I think that’s great. I wouldn’t want to write a book that everyone uniformly loved and was really easy. I’m not saying I’m trying to write books that people hate, but—

No, sure, but maybe it’s not your job to worry about how they read it.

Yeah. And I guess I just wasn’t as concerned about the violence. Certainly, I’ve seen a lot of content warnings, but I think it all fits into the mythos of Nightbitch. It needs to be there.

The parts that were kind of exquisitely bloody, I enjoyed those so much. But I got so anxious and worried about her becoming Nightbitch in social situations! Like, not now, not in the restaurant!

I’m the same way. I feel more uncomfortable when she goes full Nightbitch around people.

About a third of the way through the novel, Nightbitch notes the difference between being a woman and a dog: dogs don’t need to work; dogs don’t care about art. She also notices that since becoming Nightbitch, she’s become a better mother, and her instincts are pushing her towards being an artist again, too. What I’m wondering is—do we care too much about the wrong things?

Yes! Yes. I’ve been thinking a lot about this, especially with women—how we are conditioned to be so competent and so ready for everything. More so than boys are conditioned, right? I’m definitely one of those overachiever types, who is always like, I can do anything! You need me to do something? I will figure out how to do it faster than you need me to do it. It’s like that sort of thing.

I really feel like underachieving can be an act of profound self-care and radical feminism. To say, I’m not going to learn any more competencies, I’m done with that. I am my competencies, and my talents are here to serve me. And I’m going to protect those. They’re not to be given away. I’m not here to overachieve in service of other people. I’m here to focus on my dreams and my goals.

I think that’s what she’s trying to untangle in that little section. If I do this, I’m happy. How to untangle all of this stuff? This instinct and this ambition and this love for my child? How do I make it all work? She makes it all work by getting really clear about what she needs, what she has to give, and focusing solely on that and not being distracted by all these people who want things from us that take our energy.

Do you think most artists can benefit from reaching into their more feral, nature-driven sides?

I guess it depends on what sort of artist you want to be. You have to be open to being in touch with a reality that most people aren’t walking around in. And if art is not only what you do, but how you lead your life, if you’re committed to an artful life, what does that mean? We take all this stuff, and we turn it into words, and we put it on paper. We’re not working with clay or working with paint or immediately in touch with a form. If there’s some part that we need to be in touch with, it might be the chaotic part of ourselves. I would liken chaos to nature, and believe there is some need to move into nature and into chaos, and into seeing a new arrangement of the world. Because isn’t that what we’re trying to do? We’re trying to see through the scrim to understand what’s really going on and capture that on the page somehow. In that way, we’re trying to commune with nature.

Another way of saying it is, when you go to make art, when you go to write, you have to de-rationalize yourself, right? You enter into an irrational space; you’re not there to find really good points. You’re there to investigate utter chaos. Of course, you can’t always de-rationalize yourself, you have to come back. And so, it’s this constant touching of two worlds—going in and saying: I don’t know why I’m writing. I don’t know why I’m writing a book where a mom turns into a dog.

It seems like the worst fucking idea I could think of. And yet, I’m going to enter into this deeply irrational space and see what happens. Art gives us a place to be irrational, be wild, be an animal. And then it’s so lovely because we also have our big rational brain to give it order.

How did The Field Guide to Magical Women become a part of Nightbitch’s story?

I think I’ve found what my writing tic is, and it is writing a book and then putting another book in the book.

Is that something you’ve done before?

I have an abandoned novel—I wasn’t very deep into it. It also has a made-up holy text within the text, which then I just wanted to write. I have this impulse to figure out where to put the things I wrote in my MFA! I wrote these beautiful little, you know, lyric essays when I was in my MFA program. Like, what is this? But then I thought, oh! That could be a thing within a bigger thing. I do have an affinity for mysterious, beautiful little texts. So that’s part of the reason it showed up in there. It’s also such an ingrown instinct for me, if I have a question, to go and get a book. So again, it’s just natural. Of course, you go to the library! That’s what everyone does.

So the novel ends, to put it vaguely, [minor spoiler here] with a performance that organically integrates her son, and suggests acceptance and recognition from a discerning audience. It feels like a real curtain call. But I wonder, what happens next for Nightbitch?

I think it’s a great question.

I also know that you’re probably like, I ended the book there! I don’t have to keep writing it!

I don’t know that it gets easier. I think it gets different. She’s not holding the anger in her body anymore. She’s using it, and it’s propulsive. She’s learned how to harness it and to focus it, which has been this huge gift, and she has worked through it. [All the characters] are in a different place, but it’s still going to be this negotiation of who gets what time, and how do we make this all work? But she’s moving now. She’s moving, and I don’t know where that’s going to take her but to the fact that she is not stuck. She’s not stuck in the house, stuck in her feelings. She’s able to move and I have a lot of hope and confidence in her that she’ll keep moving. It would take a lot to get her to stop.

I love what you said about it not being easier, but different. And that seems like maybe the most hopeful thing any of us could ask for after this year and a half, things feeling so static in a lot of ways. Difference is vital.

My therapist always says that your feelings have a beginning, a middle, and an end. There’s a narrative arc; there’s movement. I’ve seen that I can just get stuck. Like, I’ll say, No, this is where it stops. And I keep returning to the beautiful comfort that the structure of a story can give us. Not only in storytelling, but also as we try to work through our daily lives. There’s a beginning and a middle and an end, like everything. You just gotta keep it moving! It might not get easier, but it’ll be different. And you’ll be someplace new. And then you can keep moving from there. That’s really all I know at this point. And that’s what Nightbitch gave me.