In his inaugural food column, Beowulf Thorne included recipes for gingerbread pudding, Thai chicken curry, and vanilla poached pears, plus a photo of a naked blond man spread-eagled in a pan of paella. Eat your cereal with whipping cream, he advised readers, and ladle extra gravy onto your dinner plate. “Not only does being undernourished reduce your chances of getting lucky at that next orgy, it can make you much more susceptible to illness, and we'll have none of that,” Wulf wrote.

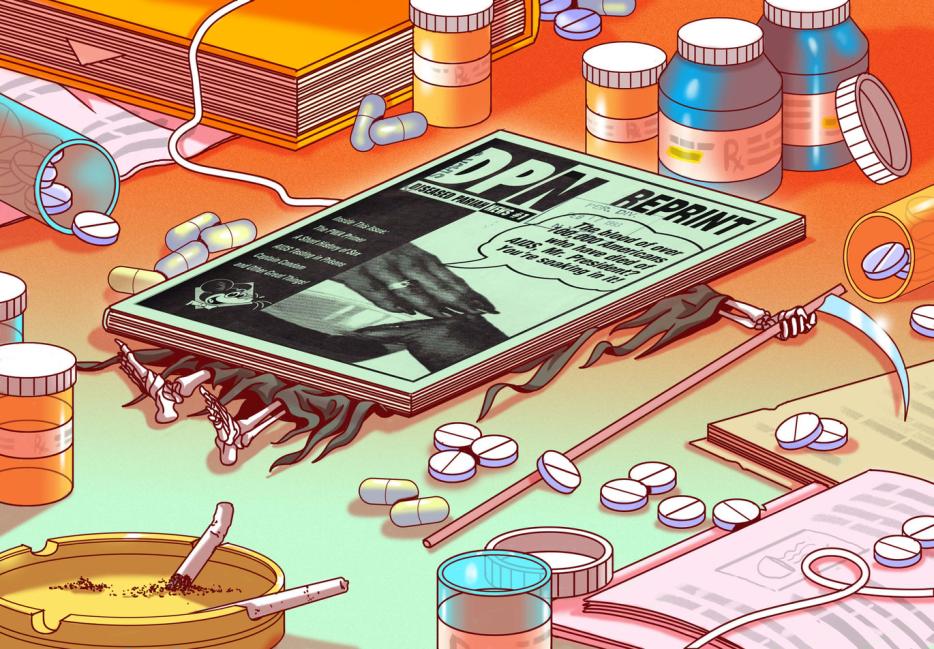

“Get Fat, Don’t Die,” the first cooking column for people with AIDS, ran in every issue of Diseased Pariah News, the AIDS humor zine that Wulf started and edited from 1990 to 1999. Under the byline “Biffy Mae,” he passed along reader recipes, mocked nutritional supplements marketed to people with AIDS, and leaned into Bisquick, his tastes alternately cosmopolitan and straight-from-the-box comforting.

Telling readers with T-cell counts in the double digits to lard their food with Paula Deen-ian levels of cream sounds like nutritional heresy. Yet Wulf’s advice echoed the recommendations that doctors and nutritionists were giving patients with AIDS wasting syndrome. “The famous expression ‘You can’t be too thin or too rich’ was obviously coined before the AIDS epidemic,” Wulf wrote. As the paella nude signaled, his column claimed the right to pleasure, but in each recipe was embedded an urgent appeal that recipe writing of the 1990s had dispensed with: Eat so you can survive.

I came across “Get Fat, Don’t Die” in a queer library in Minnesota in 1991, the summer after my sophomore year in college, and its raw, punk camp electrified me. The memory erupted out of some dark pool several years ago, and I eventually traced the column to the archives of the GLBT Historical Society in San Francisco, which had accepted Wulf’s papers as he was dying. The organization had digitized all eleven issues of Diseased Pariah News, they told me, and emailed the link. It electrified me all over again.

***

According to his friends, Jack Foster’s arrival in the Bay Area in 1983 was as much an escape as a pilgrimage to the West Coast’s gay sanctuary. Escape from the denunciations of his father, a military contractor in Southern California. But also escape from the older gay men who’d taken him in several years before as their underage sex pet. He moved to Palo Alto and began attending the Stanford Gay and Lesbian Alliance, which was open to nonstudents. He was eighteen, and already infected.

Jack soon moved into a household whose inhabitants and visitors—Stanford grad students, activists, budding software engineers—called it “Listing Shambles.” Birth names at Listing Shambles were shucked as readily as the sheets at their toga sex parties. Jack Foster re-christened himself Beowulf Johan Heinrich Thorne, or when the camp flared particularly hot, Biffy Mae.

Tall and lean, striking or anonymous depending on the angle, Wulf had a slim face whose stern, L-shaped nose fought against the sensuousness of his bottom lip. He wore round wire-rim glasses with lenses thick enough to form a white ring and moussed his blond bangs into a studied flop. He considered himself a perennial twink. Or, really, a nerd, his friend Kira Od said, whose big feet always seemed to be in his way. And yet, she added, he was naughty.

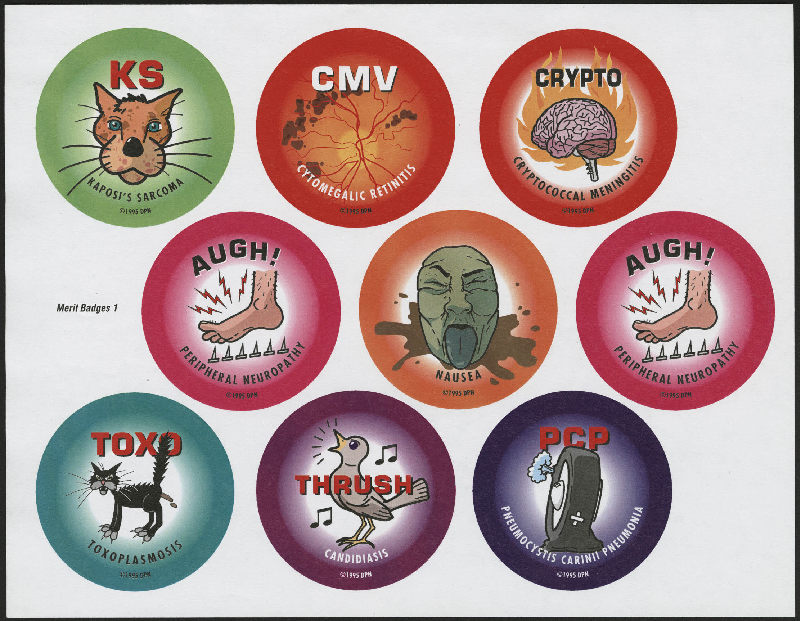

Paper merit badges for DPN buttons, Thorne (Beowulf) Papers, Courtesy of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Historical Society.

“He had a deep and abiding sense of black humor,” agreed Arion Stone, his roommate at Listing Shambles. Friends remembered that Wulf gardened masterfully, but only toxic plants, and burrowed into esoterica like tillandsias or Russian noun declensions. He cooked and cartooned and wrote and gardened with what Arion called a “sublime self-assurance about his abilities.”

After a year or two in Palo Alto, Wulf earned a scholarship to study bioscience at UC Santa Cruz, working on safe-sex education causes with the Stanford crew in his spare time. But as his senior year approached, the virus began making sorties in his system, and Wulf realized he wasn’t going to live long enough to earn an advanced degree. He dropped out of school and took up graphic design, just as desktop publishing software supplanted pasteup boards and typesetters. A job at Addison Wesley designing scientific textbooks allowed him to move to San Francisco in the late 1980s. There, his roommate was Tom Shearer, a technical writer with an acerbic wit and a lower T-cell count.

Inspired by ACT UP but too introverted to join its protests, the two came up with their own way to fight the stigmatization and mawkishness of the epidemic: humor.

***

Twenty-four years after protease inhibitors and combination antiretroviral therapy (the “cocktail”) brought the immune systems of millions of HIV-positive people back into healthy ranges, it’s hard not to read Diseased Pariah News without straining for a happy ending. Hang in there for a few more years! the brain shouts at each page. The same thinking that collapses World War II into a moral victory and the Civil Rights Movement into a triumph has recast the plague years as a self-contained tragedy.

Yet to laugh at Wulf and Tom’s jokes—to take in the full spectrum of the rage and grief coded into each shocked laugh he drags up from your chest—requires you to strip away the safety of history.

In 1990, the cocktail was an untested theory; on the market was nothing but death and toxic drugs. Despite the rising numbers of infected women and children, and the devastation the plague wreaked on the trans community (with little mention in the press), AIDS in North America was twisted up with gay identities. When U.S. scientists first observed a cluster of strange illnesses and deaths they dubbed Gay-Related Immune Deficiency in 1981, the LGBT movement had only asserted itself publicly for a decade or so. It was still so fragile, so niche, that most people outside major cities had never encountered LGBT people before they saw photos of young queer men with sunken faces, covered in purple lesions, in the news. It confirmed to some that God was punishing this aberration the moment it denied its sinfulness.

For many older gay men and trans folks, AIDS snatched away everything they’d made of their lives and poisoned the raucous liberation of the 1970s. To children like me, only ten when GRID appeared, coming out into the plague meant love and rejection and sex and hideous death would knot themselves up so tightly we could never tease the strands apart.

By the time DPN published its first issue in 1990, four people were dying of AIDS every hour, and the U.S. death count was rocketing up to 100,000. According to David France’s How to Survive a Plague, by then at least 20 U.S. states had considered quarantining people with HIV in camps, arresting them for having sex, or even tattooing their status on their bodies. Hate crimes spiked across the country, to the indifference of many police departments.

For all the services—hospital wards, pet care, volunteer housecleaning, support groups, hotlines, meals—that community groups constructed in the absence of government support, the first generation of helpers were burning out and the death rate wasn’t slowing down.

That year, many say, marked the darkest period of the epidemic. For Wulf and Tom, turning the plague into a sick joke was a radical act of self-love.

***

“A few years before I had seen a bitter little cartoon,” Tom wrote in the introduction to the first issue. “An airline had refused passage to a person with AIDS, and there was a big stink about it. The cartoon showed a man at an airline counter, and the clerk was saying ‘And would you like the smoking, non-smoking, or diseased pariah section?’ Mr. Tom was much impressed by this terminology and began to refer to himself as a diseased pariah, to much dismayed fluttering from his friends. At the time, remember, the only acceptable role for an infected person was Languishing Saint and Hug Object.”

Tom wrote half of the text, Wulf the other half, under such pseudonyms as “Serene Editor” (Tom) and “Cranky Editor” (Wulf). Wulf repurposed the “Captain Condom” comic he had invented in the course of his safe-sex education work and laid out the issue on legal paper, folded in half and stapled. They filled Diseased Pariah News with stunts, porn reviews, comics, naked centerfolds, erotic anecdotes from a well-known sex worker titled “How I Got AIDS,” and personals.

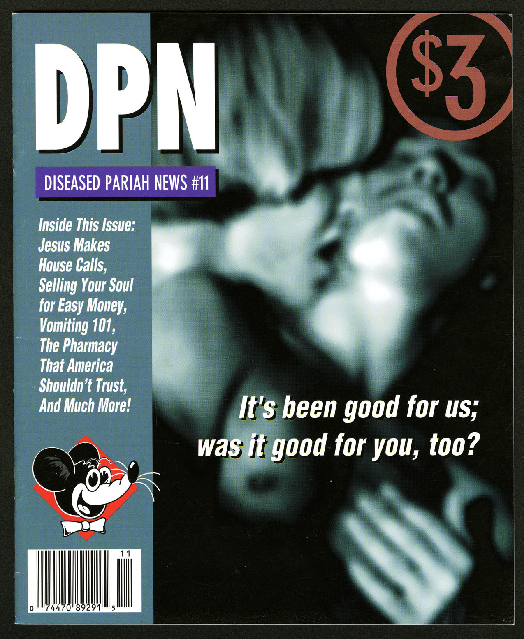

# 11, Thorne (Beowulf) Papers, Courtesy of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Historical Society.

The recipes in the second issue, printed alongside recommendations for eating when you had diarrhea, ranged from the ambitious to gluttonous convenience: Biffy Mae’s Totally Amazing Gumbo. Marcus Mae’s Roast Chicken of the Ages. Danny Mae’s Fat Boy Shake, which combined Ovaltine and instant breakfast powder and could be powered up with two scoops of ice cream. Wulf tested every recipe, nudging them into shape. He took the column’s blunt title in earnest. The jokey names and camp flourishes kept his earnestness at a safe distance; too close, and the fear and physical discomfort and bitterness could smother.

***

As Biffy Mae wrote in that second issue, “One of the most exciting aspects of the HIV Early Retirement Plan is what it may do to your innards.”

Wasting syndrome, which one third of all people with AIDS experienced then, wasn’t just one of the most common effects of HIV. It was the look of AIDS: Arms devoid of muscle and fat, the humerus, radius, and ulna so exposed that you could read the knobby topography of the joints that connected them. Hips that were no longer hips, legs no more fleshy than a water bird’s. Faces whose skin draped lightly over bones and hollows, faces made unrecognizable by the obliteration of fat and muscle. You could go back to work after a case of pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) and pretend it was a regular illness, or cover Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) lesions with clothing if they were in the right places. There was no disguise for wasting.

And yet the most prominent memoirists and fiction writers who chronicled the plague years—Harold Brodkey, Larry Kramer, Paul Monette, Hervé Guibert, David Wojnarowicz, Adam Mars-Jones, Allen Barnett—barely invoked its horrors. So many of the narratives of the time circled around two themes: memorializing the terror and adulterated sweetness of being alive as everyone they knew was dying, and shearing through the cordon of dehumanizing indifference that the public had erected around plague-struck communities. The experience of daily diarrhea or constant nausea may have been too visceral, too private, or simply too grinding to fit into the arc of a plot. And so, for all the poignancy that lingers in the public's understanding of the plague era, the lived experience of wasting has faded out, vivid only in the memories of survivors and medical researchers who had tried to halt its progress.

Wasting only appeared when the body’s CD4, or T-cell, count dropped from over 600 per cubic microliter of blood to under 200, Mark Jacobson, a physician and researcher who worked at San Francisco General Hospital in the 1980s and 1990s, told me. People weren’t only dying of opportunistic infections. They were dying of sheer malnutrition. “Loss of lean body mass was one of the most powerful predictors of when people were going to die,” he said.

As the body’s immunological systems shut down, bizarre symptoms seemed to pile up. Diarrhea could last months, the intestines gleaning whatever nutrients they could catch as the food luged through them. The diarrhea could be caused by mycobacterium avium-intracellulare or by parasitic infections like cryptosporidium and microsporidia that wouldn’t respond to drugs. HIV alone could cause the entire gut to become inflamed.

But diarrhea was only one of the factors that caused wasting, said Kathleen Mulligan, a retired faculty member in the UC San Francisco endocrinology department who studied wasting in the 1990s. “It turns out the main factor contributing to wasting was the inability to eat enough food to cover their energy needs,” she said.

Even people never given a formal diagnosis of wasting syndrome struggled to eat. “It’s striking how rapidly eating becomes a chore when it ceases to be pleasurable,” she explained. “The drugs made the food taste bad or different. People had painful ulcers or sores in their mouths, so it was difficult to tolerate food. Couple that with stress and depression, nausea from both the disease and the drugs to treat the disease—it was easy to tell people to eat more, but not that easy to find a way to motivate people to get the food they needed.”

Any relief was worth trying. Anabolic steroids. Human growth hormone. Testosterone. Megace, a drug that exchanged weight gain for sexual desire. Heaps of vitamins. Wheatgrass juice. Kombucha. Pau d’Arco. Synthetic THC. Homeopathic drugs. Macrobiotics.

If the scientific consensus was that high-calorie food was the best treatment, sometimes improbable measures brought relief. Vince Cristostomo, who now leads the San Francisco AIDS Foundation’s network of long-term survivors, was diagnosed with wasting in 1989, when his weight plummeted from 145 to 119 pounds. He felt as if his body was eating itself alive. He wore baggy clothes to cover his too-thin limbs, but his skin turned gray.

With an immune system so dysfunctional, everything made him sick. “I learned that if I ate certain processed foods I’d get chemical burns in my mouth,” he said. “I drank white rice and it turned to alcohol in my stomach.” Hosts of food allergies appeared.

A friend helped him attend an “instinctive eating” program in Europe that put him on a raw-foods diet, and that infusion of nutrients, he said, made a massive difference. For months at a time all he could eat was macrobiotic broccoli and brown rice. He had grown up in Guam, where the food was highly flavorful, and he thought to himself, well, if this is how I have to eat for the rest of my life, I will do it. The weight returned, and stayed with him long enough for the cocktail to come along.

***

Between the publication of issue two and three of Diseased Pariah News, two significant events occurred.

Surprising its editors, the zine got famous. In 1991 SF Weekly, New Republic, Los Angeles Times, and Newsweek all wrote about the shocking notion that people could make fun of the disease killing them. In the contact sheet from DPN’s first publicity shoot, which provided photos for some of these articles, a healthy Wulf and a cavernous Tom posed on Tom’s hospital bed. They played it straight for a few frames, then Tom lolled on his bed like a 1930s pinup girl, two wrist-thick thighs emerging from his gown. Wulf joined for another frame to strangle Tom with his oxygen tube.

Tom, whose dementia had made a begrudging caregiver of his roommate, died a few weeks afterward. Before, though, he used his credit cards to charge thousands of dollars of equipment for Wulf to use on the magazine. With Tom’s creditors harassing him daily and more symptoms appearing, Wulf left San Francisco to return to Listing Shambles in Palo Alto.

“Darn! One of our editors is dead!” Wulf titled Tom’s obituary, and promoted him to “Deaditor.” Daniel Bao, one of Wulf’s best friends who took charge of the magazine’s operations, said their circle of friends sprinkled some of Tom’s ashes into plastic resin to make nightlights.

A newcomer named Tom Ace, a computer engineer who had first encountered Wulf through his personal ads, stepped in as the publication’s Humpy Editor. What drew him to DPN, Ace says, was a stance no other publication dared take on. “No denial,” Ace said. “No pretending it isn’t the way it is.” No spiritual balms, no stigma, no shame, no sentimental bravery. They were people dealing with an illness, not the victim-perpetrators the media made them out to be. They were still having sex, and watching porn, and posing for nude centerfolds that ran with their T-cell counts and list of meds.

"We think that if you're going to croak sooner than you'd like, at least you can live while you're alive,” Wulf told the LA Times.

***

Ned: Why are you eating this shit? Twinkies, potato chips ... You know how important it is to watch your nutrition. You’re supposed to eat right.

Felix: I have a life expectancy of ten more minutes. I’m going to eat what I want to eat.

— Larry Kramer, The Normal Heart

***

Paul Monette wrote in Borrowed Time, a memoir about his partner’s 1985 death, “It turns out a home-cooked meal offers a double dose of magic. At the same time you’re making somebody strong again—eat, eat—you are providing an anchor and a forum for the everyday.”

Sometimes cooking, like black humor, could save the life of the cook, too.

Fernando Castillo, whose recipes formed the culinary backbone of Project Open Hand in San Francisco, said that cooking for the organization in the 1990s was the only thing that assuaged the pain of a decade of horror.

After his lover died of AIDS in the very first wave, Fernando had moved into a large Victorian flat in the Mission, San Francisco’s Latino neighborhood, with his closest friends. But death chased him. One by one, his “babies”—his brothers, his sisters, his chosen family—got sick. So did the landlord upstairs. The Polk Street Mexican restaurant where he was chef closed in 1986, and he was too busy caring for his babies to look for another job.

He became the building’s main caregiver, bringing in more friends after others died. He would go from one bedroom, where one of his babies was vomiting, to the next, where another’s fever was spiking. He would take them in taxi cabs to the hospital so frequently the nurses knew his name. And, from morning to night, he cooked.

“I learned that I had to give them something not too heavy, but at the same time nutritious,” Fernando said. That meant chicken soup loaded with vegetables, stews made with the best meat he could afford, rich stocks with bones or fish heads. A lot of rice, and a lot of beans.

Some of his babies had such bad cases of thrush—an overgrowth of yeast that coated throats and tongues in irritated white fur—that he had to puree the stews. Others, who were taking AZT by the fistful, developed weird allergies or lost the ability to digest dairy or beans. There were few social services for people with AIDS in those days, but people in the Mission found out about what he was doing. They would pass along some money. Markets would slip in extra meat, or charge him less. He took care of his seven friends until they died.

In 1991, the last of his babies gone, he was considering whether to accept his sister’s offer of a plane ticket back to their hometown in Mexico. Then Ruth Brinker, the founder of a San Francisco meal service called Project Open Hand, asked him to come in to the kitchen help her out. “Instead of being in mourning in an empty apartment, I joined Project Open Hand,” he said. He adapted all the dishes he had written down in a tiny booklet so they fed thousands of people a day.

***

In the middle years of Diseased Pariah News’s run, Wulf and Tom Ace were joined by a Sleazy Editor, Michael Botkin, a journalist famous in the Bay Area LGBT community for his “AIDS Dispatches” column and equally dark sense of humor (“dead meat specials,” he once called people with AIDS). The zine’s circulation rose to three thousand, sold at LGBT bookstores and Tower Records around the country. Tom now recalls that people would stumble across an issue, write to the editors, and order the entire back run.

The editors always intended to publish four issues a year, but only managed two or three. They’d call in their friends for assembly parties, Wulf fretting over the placement of each “Not Sanitized for Your Protection” paper band they wrapped around the zine, scaring off casual browsers.

Any idea that would double the editors over with laughter made it into the magazine. They recorded parody songs on a flexible vinyl single and stapled it into the zine. Wulf devoted a number of spreads to AIDS Barbie and KS Ken, wasting away so attractively, their lesions courtesy of a blowtorch. “Kiss me, I’m a diseased pariah!” T-shirts and buttons sold by the hundreds, helping to cover the production costs. They also marketed “AIDS Merit Badges,” each depicting an opportunistic infection or alarming T-cell count (achievement unlocked!), for people to wear on a sash to their medical appointments.

Readers sent in poetry and essays they hoped DPN would run, not to mention dozens of recipes, each of which Wulf would retest: Calorie-Packer Hash. Mysterious Cheese and Nut Loaf. Hard-Hearted Hannah’s Pecan Buttercrunch. It was food for when you weren't sure you wanted to eat, food that might just keep you alive. But Wulf wanted it to offer pleasure, too—and whether the appeal was trashy or refined didn't matter. Larding a zine about AIDS with recipes didn't just add a note of domestic camp that Biffy Mae, toxic-plant aficionado, clearly delighted in, the recipes interrupted the zine's dark humor, visually as well as psychically. You may be dying. Fuck. Buy yourself a box of Bisquick and make this berry dessert.

Alongside the recipes, “Get Fat, Don’t Die!” covered avoiding possible parasites in sushi, eating when you had nausea, shopping on food stamps, and compensating for the taste perversions caused by drugs like AZT. (“Some liken it to a metallic taste, sort of like having a bloody nose all the time,” Wulf wrote.) DPN may have been the first AIDS-related publication to instruct readers on making pot butter to bake into brownies to combat nausea and lack of appetite. The medical marijuana movement took off in San Francisco in the early 1990s, when Brownie Mary delivered edibles to AIDS wards and activists set up smoking lounges for the chronically ill.

In my favorite column, Michael and Wulf, who had “AZT butt” themselves, tasted every chocolate dietary-supplement shake doctors were pushing people with wasting to drink. Every one of them was chalky and tasteless, they concluded, and ran a recipe for mole poblano alongside.

These were the issues I must have encountered in Minnesota, and I remember flipping through them with a mix of awe and shame. Was it worry that someone might see me reading an AIDS zine and think I was HIV-positive? The sense that I had stepped into a room that wasn’t built for me? The constant guilt I felt, as a healthy 20-year-old, as if I was skipping across my elders’ graveyard? All of those, most likely.

Now that I am decades older than Wulf was then, the gall of the magazine—to mock death, and shame, and governmental neglect, and all the squeamish attempts at empathy AIDS occasioned —strikes me as a form of redemption. And to snicker at Wulf’s jokes, each laugh tinged with the grief and horror I thought long buried, feels like the best way to honor him.

***

As neuropathy—probably from the fistfuls of AZT—made walking harder and cytomegalovirus retinitis ate away his field of vision, Wulf secured disability leave from his day job in the mid-1990s and retreated to a house he shared with Arion. DPN remained one of his main pursuits, along with gardening and fighting with his insurance company, but it took longer and longer to put out a new issue. Six months. A year. Two. Michael Botkin, the Sleazy Editor, died in 1996. Tom Ace, Humpy Editor, left the Bay Area for the California desert. Protease inhibitors appeared, but Wulf’s body was too worn out by then to benefit from them.

When Wulf died in 1999, at the age of thirty-four, he had readied the eleventh and last issue of Diseased Pariah News, complete with a years-old obituary for Michael (“He had looked like death warmed over for so long, we never thought he’d really die!”) and a parody ad for AZT Lite. Tom Ace and Wulf’s friends added a tribute to Wulf and sent it out, secretly sprinkling Michael’s ashes into a few copies.

They played around with the idea of turning Wulf into a snow globe, but they couldn’t figure out how to make cremains float in a viscous mix of Astroglide lube and water, and they didn’t want to offend his mother, who had come up from Southern California to tend him in his last few weeks. At the “celebration of his extinction,” she surprised them by wrapping the box of her son in shiny gold paper. “I think he might appreciate it,” she said.