If you consume Jean Rhys’s first four novels one after another, the books begin to bleed into each other. You may try to be logical, making a note of names and ages. There are, after all, four different protagonists: the 18-year-old chorus girl Anna Morgan (Voyage in the Dark), the 28-year-old wife Marya Zelli (Quartet), thirty-something Julia Martin (After Leaving Mr. Mackenzie), and the middle-aged woman Sasha Jensen (Good Morning, Midnight).

But after a while, the protagonists start to look like the same person, distorted in funhouse mirrors—this one a little younger, that one a little poorer, one with a fur coat, one who has already sold hers. They are all, even Anna, sad about aging and obsessed with clothing; they’re largely underemployed and dependent on the palely awful men they date for food, board, and taxi money; they flit from depressing lodging to depressing lodging, and they spend the course of the novels inhaling one drink after another.

It’s tempting to chalk these similarities up to the novels being largely autobiographical: if the heroines are the same person, maybe that person is Rhys herself? Indeed, in an essay in The Guardian, her Wide Sargasso Sea editor Diana Athill argues that Rhys’s novels were “based on things that really happened.” Several details from Rhys’s own life neatly dovetail with plot in her work: the chorus girl career and abortion in Voyage in the Dark, the affair with Ford Madox Ford in Quartet, the characters’ drinking habits through all four novels.

But are these novels really best consumed as autobiography? These four books seem at their most powerful in portraying a general female melancholy that speaks to the conditions of the interwar years rather than one specific to Rhys herself. The financial precarity, the hostile landladies, and the blurred line between dating and sex work sound all too familiar when we look at the historical context.

Of course, the geography of these novels matters, too. Nothing feels more characteristically Rhysian than Quartet’s Marya gazing down the Rue de Rennes in Paris and thinking of Tottenham Court Road or Leaving Mr. Mackenzie’s Julia spending 600 francs on new clothes before her trip to London in the hope of looking respectable enough for her family to welcome her. Rhys’s novels are obsessed with England and Englishness,11I will be using the terms “England” and “English” in lieu, in places, for “Britain” and “British” throughout the essay since these are the words Rhys uses over and over in these four novels.regardless of where they’re set. But while her heroines are preoccupied with a sort of establishment Englishness that they feel shut out from, Rhys (who was born and grew up in Dominica) uses these novels to portray a new form of Englishness. Her take on Englishness is markedly multicultural, reflecting how the British colonies have disrupted and dispersed English identity.

These novels suggest that to be an English woman in the interwar years is to be unhappy, no matter where you were born or where you live. In Voyage in the Dark, Germaine, a French woman, says “Scorn and loathing of the female—a very common expression in this country… I wouldn’t be an Englishwoman… for any money you could give me or anything else.” In Good Morning, Midnight, a male escort named René claims, ‘“England isn’t a woman’s country. You know the proverb—‘Unhappy as a dog in Turkey or a woman in England’-?”’ In her short story “Till September Petronella” (published in 1960, but written in the ’30s), we hear the same old ditty from an English man himself, someone from the heart of the establishment, telling the eponymous Petronella, “You poor devil of a female, female, female, in a country where females are only tolerated at best!”

In Voyage in the Dark, a suitor asks Anna about her work as a chorus dancer, her accommodation in lodgings. When he finds out her wages, he responds, “Good God… You surely can’t manage on that, can you?” How did a generation of women make things work when their wages and bills didn’t quite equal out?

***

In the years Rhys was writing about, two competing fairy tales were being circulated. One was heartening. Things had changed forever for women in Britain. After a surge of women into the workplace during World War I, the gentler sex were on an almost-equal footing to men: they worked, lived in lodgings in big cities, drank, dated. Flappers existed! Everything was thrilling.

The other fairy tale was comforting, like someone rocking you back to sleep after a bad dream. After women held the fort while British men were away fighting, now the men were back and the old order could resume. Women could work for a while if they liked, could live in lodgings if they liked, but the vast majority of women would end up marrying and dropping out of the workforce. They would be financially cared for by men or by their families.

The truth, situated in the space between the two competing narratives, is painfully clear in numbers. In her study on British lodgings, British Boarding Houses in Interwar Women’s Literature: Alternative domestic spaces, literary critic Terri Mulholland notes that the number of single women over the age of twenty-five increased by over half a million between 1911 and 1931, which meant they outnumbered single men. This is presumably a disparity partially caused by the loss of male lives in World War I, a disparity which would have felt particularly exaggerated in the middle and upper classes, since the largest loss of life was sustained in the officer class. She tells us that 50 percent of women who were single in their late twenties in 1921 were still single a decade later.

The obvious conclusion is that women whose families were unable to support them would have gone out to work. But Neal A. Ferguson reports in “Women’s Work: Employment Opportunities and Economic Roles” that throughout 1911-1931 approximately one-third of all “employable women” had jobs. In Good Morning, Midnight, Sasha’s hostile English employer asks her to explain a five-year-long gap in her resume and draws his own conclusions with a sneer. But this wouldn’t have been uncommon. As Ferguson explains, “Underemployment was not a temporary condition; it typified women’s economic position.” While women were eligible for unemployment benefit, their benefit was set at a fraction of what was granted men.

Counterintuitively, the number of women in lodgings soared in Britain, implying women were no longer living with their families. A lodging or boarding house was a house in which a person could rent a room. According to Kate Macdonald, lodging houses were structured differently depending on the class of their guests—“there were ‘common lodging houses… hostels for the poor and homeless.’” In these houses, multiple beds would be crowded into one room. “Next up on the scale was the rental of a room rather than a bed.” This is the sort of lodging Rhys’s heroines stay in, but Macdonald emphasises that even within this point on the scale, there was slippage: “At its worst this room would be in a crowded slum building, with a bare minimum of furniture and heating, and no means of cooking other than at the fireplace.” Mulholland observes that between 1861 and 1911 the number of female clerical workers in London more than doubled. She concludes that the increase in women workers resulted in an urgent need for affordable housing “that was simply not available.”

What these statistics depict is a society out of step with reality. It was a system, for the most part, structured around the idea that women would be financially provided for by their husbands or their relatives. But there weren’t enough men for women to marry their way into financial security and even middle-class families no longer seemed to be financially stable enough to provide for their daughters. The wages women earned, at approximately half the male rate in most industries by 1931, probably weren’t high enough to live comfortably on while paying the rates demanded for “respectable” lodgings. While Mulholland notes that boarding houses “run by philanthropic organisations” did offer some women on lower incomes cheaper rooms, these were primarily targeted at women under the age of 30, contributing to the idea of lodgings as a short-term solution for working women before married life.

***

In Rhys’s books, many heroines come close to going broke. And it is part of these novels’ very particular brand of tragedy that when our heroines work (and for much of these novels, they’re supported by men), they are mostly drawn to professional roles with a built-in expiry date. It would have presumably been more challenging to make a living as a forty-year-old chorus dancer or a forty-year-old artist’s model or a forty-year-old shop mannequin, than a clerk, for example. And this isn’t broadly representative of Britain at the time—according to social historian Katherine Holden, during the 1930s nearly a quarter of all occupied unmarried women worked in retail or clerical work.

A secretary or a typist or a shop assistant might not have to be young in the same way a chorus girl would to hang on to their job, but ageism was still prevalent: Holden notes that 75-80 percent of workers in these areas were under the age of thirty. In her study of British lodgings, Mulholland quotes an unemployed 38-year-old woman seeking office work: “I went to the Employment Exchange and to my utter astonishment I was told my age was against me. Now I was made to realise that having put 38 as my age on application forms, no employer had any use for my type of services.” The same woman makes a confession straight out of the pages of After Leaving Mr. Mackenzie: “I am tired of the struggle […] I am always hungry. All I can do all day is wander about the streets. No one needs me. There is no place in the world for me.’”

These precarious conditions didn’t go unchallenged by the women they affected. In 1934, Holden reports, a group of middle-class women in central London set up the Over Thirty Association, a group formed to campaign on two problems. The first was female unemployment, which was “widespread” at the time, but the second issue was arguably even more pressing: the deplorable living conditions that so many unmarried women tolerated.

***

Rhys’s heroines are grappling with alcoholism and brutal misogyny and mental health issues, but to compound these problems, they have no permanent home—just rooms in boarding houses and hotels. They could get kicked out of their lodgings any time, and they do, over and over again. There’s Anna in Voyage in the Dark, whose landlady gives her the boot after she gets new clothes and comes home late a couple of nights in a row. In Leaving Mr. Mackenzie, Julia’s lover insists she bring him back to her London boarding house—he suspects they might get caught and she might get kicked out, and that’s his kink. And sure enough, she does.

This wasn’t a problem specific to Rhys’s characters—this was an interwar issue. Holden writes of an “invisible majority” who “lived in lodgings, boarding houses or institutions or who had no permanent home.” In a boarding house, Holden notes, bachelors were given the “services usually offered by a wife,” like help with housework, meals and laundry. Despite women paying the exact same rent on less wages, these services were rarely included for female boarders and it was common for landladies to regard their female tenants with suspicion. As Mulholland notes, unmarried landladies with no male relatives living in their boarding house were at risk of their establishments being labelled brothels.

The way out of this precarious housing system—buying property—would have been unachievable on the average female wage of the time. So, what would you do as an unmarried woman trying to live comfortably, instead of paycheck to paycheck, or save money in the years between the wars? Possibly, you’d have supplemented your wages as an amateur sex worker.

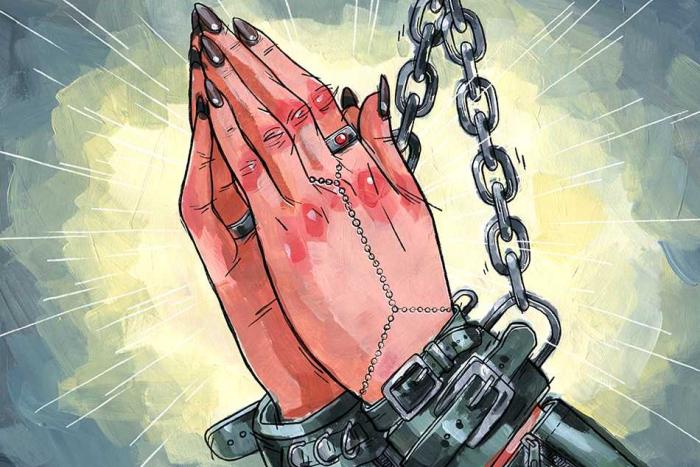

Rhys’s heroines usually “manage” by supplementing their income by moonlighting this way. As literary critic Sue Thomas has noted, this isn’t as clear-cut a deal as traditional sex work—instead of settling on a price from the beginning, the exchange would be “implicitly negotiated,” with sex made available in exchange for gifts of money and clothing, dinners out, drinks. In this exchange model, the sex worker has markedly less power and autonomy—another key difference between sex workers and their amateur equivalents is that most sex workers would have multiple clients but an amateur typically has just one. In other words, these women occupy the uneasy grey space between sex worker and wife.

In Kerry Chamberlain’s investigation into interwar sex work in Liverpool, she observes that from 1926 onwards, the number of arrests for amateur sex work “consistently, and often significantly, outweighed” the number of arrests for traditional sex work. She also observes that unlike traditional sex work (which was predominantly carried out by younger women), a wide range of women of different ages were arrested for amateur sex work, which she believes implied that women carried out amateur sex work “at different stages of their lives on a casual and short-term basis, perhaps in response to periods of economic difficulty, departing from the trade before the point at which they came to be legally recognised as ‘common prostitutes.’”

Of course, there is nothing inherently harmful about exchanging sex for money. But what’s painful about the amateur model is the way it obscures intention. The woman is reduced to acting on blind trust—that the man will be generous, that he will give her enough money so that she can not only provide for herself but set some aside. There’s no safety net here, no other clients to cushion things if he ups and leaves (which we see in one of the most upsetting novels of the era, Storm Jameson’s A Day Off). The amateur’s own feelings for the man are also entirely irrelevant: leaving isn’t an option. Which might explain Rhys’s curiously numb descriptions of the men her heroines date. This wasn’t an attitude exclusively held by those carrying out sex work. According to history writer Ellie Cawthorne, a common tip from 1930s advice columnists was to prioritise financial security above all other attractions when considering settling down with a man:

“Readers ‘were reminded that if a woman married for stability rather than romance, although she may be ‘starved emotionally,’ she would ‘at least be sure of her daily beef and potatoes.’”

***

Rhys’ first four novels all have the same stutter. They’re all compulsively, repetitively focused on Englishness, with hundreds of asides about England and English people (which are fun to read; like Thomas Bernhardt on Austria, Rhys is at her best when she’s dripping contempt for the English).

There’s Anna, a white woman who hails from the West Indies but moves to London aged eighteen—more or less exactly like Rhys herself. Marya is so English it’s repeated twice in the first ten pages, except that she’s married to a Polish man and seems so foreign that a fellow Brit isn’t sure of her nationality. There’s Julia, who grew up in England, but whose mother is Brazilian. Then there’s Sasha, who’s English but previously married a Dutch man and spent a sizeable chunk of her life in France. The novels coax out a new vision of English identity that seems to reflect the dispersed England of its colonial history. These novels seem to argue that it’s no longer only the Mr. Horsfields or Walter Jeffries of this society who are English. To be English is no longer just to be from England, but to be from everywhere and nowhere, to have no single national affiliation.

In Rhys’s early work, Englishness becomes a sort of trauma you’re powerless to shake—something which also reflects the reality of English colonial rule. England took formerly healthy countries and bled them dry. In these novels, England does the same to its women. Her characters do not enjoy the same privilege of being English as a Mr. Horsfield—they seem partially disqualified from enjoying the same automatic social acceptance by marrying a foreigner or having a foreign mother. But these women still seem held hostage by their national identity and infected by the same sadness that they associate with England. Like the countries England colonised, they’re given second-class status while remaining beholden to England.

In both Good Morning, Midnight and Quartet the protagonists talk about relocating to Paris as a great escape. But none of Rhys’s heroines can ever escape the island, not really. In Paris, at a gathering, amongst new friends, we find Sasha “talking away, quite calmly and sedately, when there is it is again—tears in my eyes, tears rolling down my face. (Saved, rescued, but not quite so good as new…)”

Considering what life for unmarried English women of the time was like, these sad, hard novels do not end unhappily. Not as unhappily as they could, at any rate. Nobody is homeless. Nobody kills themselves. An attempt at assault is averted. And despite their precarious existences, the heroines always find money somehow, from someone.

“People talk about the happy life,” Sasha says, “but that’s the happy life when you don’t care any longer if you live or die. You only get there after a long time and many misfortunes.” Sasha, along with her heroine doubles, is well on her way.