What were we obsessed with, invested in and plagued by in 2018? Hazlitt’s writers reflect on the issues, big and small.

Uchi’s mad.

First came the news that his roommates had eaten his pricey hidagyu beef. Then came a shocking discovery: the instigator of this sinister “Meat Crime” was his girlfriend Minori.

We watch, our watering mouths agape, as a deliciously marbled cut of beef drives a wedge through their Tokyo group house. Relationships crumble, life trajectories nosedive and poor Uchi still can’t get a bite of that luscious ruby red steak.

For legions of Japanese followers, and a growing Western fanbase, the Meat Crime is a legendary event in the annals of Terrace House, a reality series now closing its third season on Netflix and fourth season overall. Even as this year’s latest edition introduced us to a charming new cast in the snowy resort town of Karuizawa, Uchi’s meltdown in the first Netflix season remained the show’s gateway drug, luring North American neophytes into the swelling ranks of its #TerraceHouse-repping obsessives. Thanks to an exceptionally tender, tear-spattered slab of beef, 2018 was the year I finally convinced friends and family to experience one of the most emotionally fulfilling shows on television—the year I finally convinced myself that reality TV could be more than a guilty pleasure.

The premise is similar to shows like Jersey Shore and The Real World: six young people, ranging anywhere from their late teens to early thirties, live in a communal home and experience life lessons amid sexual intrigue. But Terrace House is subtler, and more cerebral, than its Western counterparts, unsullied by post-dated interviews, frenetic editing and other stylistic bludgeons. As the producers calmly observe their affable young cast and the stunningly appointed modernist home in which their pheromones mingle, the show blends the perky melodrama of a ‘90s rom-com with the intimate realism of a good documentary.

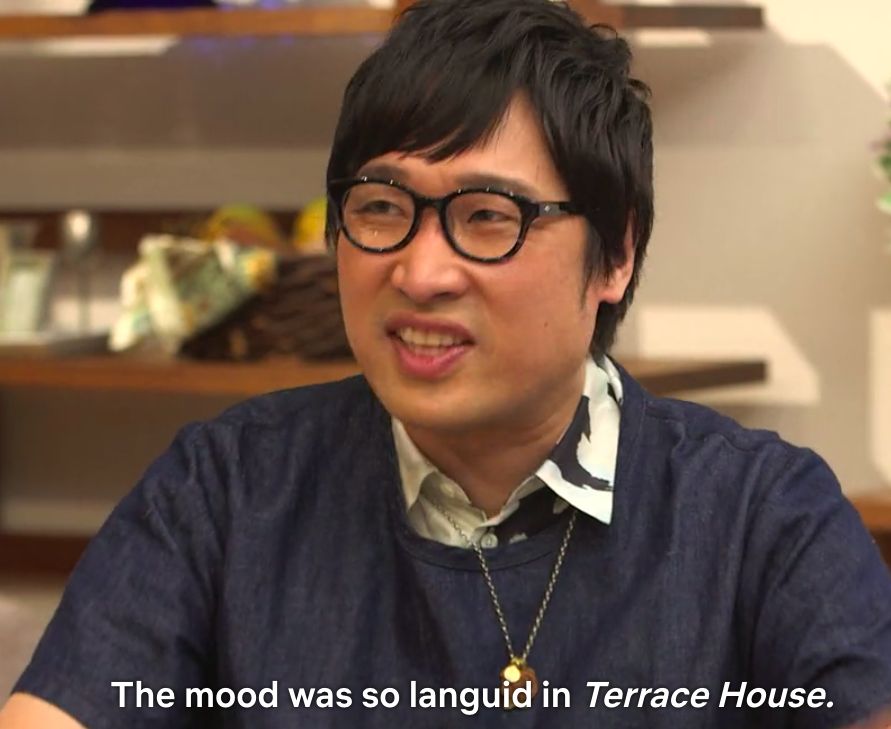

It’s an irresistible combination, enhanced by one of the great spectacles in the Netflix canon: a panel of Japanese celebrities which cuts in three times an episode to break down the latest scenes. This Tokyo-based dream team is filled with colourful characters but dominated by three performers: Tokui, a genial comedian who revels in the on-screen romances; You, a wisecracking actress with the voice of a raspy baby; and Yamasato, a bespectacled comic who delights in mocking the Terrace House residents. Because the cast members change, making way for new residents at a time of their own choosing, the unvarying panelists and their Haute Normcore outfits become a familiar bedrock. They build the kind of sassy commentary we’d normally enjoy on Twitter into the structure of every episode.

Pair this narrative ingenuity with a visual aesthetic as crisp and elegant as the best works of Japanese cinema, and you have a show that is elevating reality television to new creative heights. Ply me with enough of the fruity Merlot that boozy cast member Seina guzzles on cold nights in Karuizawa, and I’ll even argue that Terrace House is the realization of a prophecy from 1973—the year the anthropologist Margaret Mead wrote an article for TV Guide on American Family, the PBS series widely considered the progenitor of reality television. Praising the show for its innovative union of TV and documentary film, Mead declared the emerging format “a new kind of art form,” a development “as important for our time as were the invention of drama and the novel.”

For much of the past forty-five years, this seemed like a laughable assertion; reality TV has become a bastion of low culture—“the television of television,” as The New Yorker’s Kelefa Sanneh quipped in a 2011 essay. But Mead looked increasingly prescient this year. David Chang’s Ugly Delicious, Amy Poehler’s Making It and the new season of Queer Eye upgraded the genre’s timeworn formulas with rich production values and expertly plotted storylines. “Docu-series” like Liz Garbus’s The Fourth Estate and Steve James’ America to Me offered gripping, densely layered portraits of American institutions. And then there was Terrace House, looming above them all, a rising sun in a newly fertile field.

After another year with Tokui, You, Yamasato and the house members, reality TV seems every bit as engrossing as my favourite HBO dramas, every bit as ambitious as the theatrical docs that received such high praise this summer, with every kitchen clash and domestic love triangle, every spirited yelp of “kawaii!”11Terrace House’s unofficial motto: the Japanese word for “cute.” As a “Cuteness Studies” scholar at Tokyo’s Gakugei University explained in a recent CNN article, “[kawaii] communicates the unabashed joy found in the undemanding presence of innocent, harmless, adorable things.”

*

When Netflix launched Terrace House in the fall of 2015, the show coincided with a disturbing spectacle: the rising popularity of the former host of The Apprentice. Three years and countless traumas later, the “Reality TV Presidency” is one of the hottest buzz phrases in politics, summoned by New York Times reporters, cable news pundits and high-level government officials as they struggle to make sense of his dysfunctional White House.

In this climate, Terrace House flips the script, inverting the traditional dynamic between reality TV and escapism. Instead of offering a voyeuristic window onto dumpster fire behaviour, the show serves as a blissful respite from a news cycle in which that behaviour is everywhere. Some viewers compare the show to watching ASMR videos. I always think about hygge, that Danish concept of cozy well-being beloved to readers of Kinfolk. Whether we’re in the cedar-paneled corridors of the house in Karuizawa or the homey confines of the panel’s studio, Terrace House feels like a safe space.

That’s because it’s a place where kindness reigns and earnest emotion is cherished. Cast member Taishi strides into Terrace House: Aloha State, the show’s season in Hawaii, with the goal of finding “a love worth dying for.” Seina arrives in Karuizawa determined to “find [her] last love.” The incredibly formal courting rituals feel dated in the age of Tinder but it’s hard not to succumb to these gentle heartthrobs and the delight the panelists take in them. When was the last time you watched reality TV and felt as Tokui did after this season’s ice-skating date between Shion, a down-to-earth model, and Tsubasa, his hockey-playing crush: “It cleansed my soul”?

On dark nights, clouded by Trumpian gloom, Terrace House can almost seem utopian, a hope-restoring lifeline to a world of communal goodwill. It’s not a show without conflict and beef—literally, in the case of the Meat Crime—but there’s something deeply reassuring about watching best buddies set common goals and frenemies talk out their differences.

“It’s really great we can inspire each other,” an R&B singer named Shohei gushed on a recent episode, proudly informing his housemates that his band was topping the charts. As the cast members cheered in the Japanese dusk, it was hard not to agree. In a year spent lurching from headline to headline, struggling to channel my rage, the show’s celebration of friendship and love was a joy and an escape.

*

The cast of Terrace House started 2018 with a venerable Japanese tradition: the late-night slurping of noodles, meant to signify long life at the dawn of a new year. The shots of glistening soba were verses in a thrilling new language: the lip-smacking esperanto of global reality TV.

Japan’s edible rituals have always been part of the show’s cross-cultural appeal but they’ve never received more loving attention than they have in Karuizawa. The sniffing of an onion was an early season sight gag; a bowl of purple curry spawned a multi-episode meme. When an aspiring chef named Yuudai underseasoned a soup, and made the hunt for mediocre bagels the centrepiece of a date, the hapless nineteen-year-old was cooked. He had insulted the twin pillars of the Terrace House community: the relentless pursuit of personal improvement, and the bonding of friends and lovers through cooking, eating and drinking. The dinnertime meals improved after Yuudai departed the show, but his early exit dashed our hopes for a sequel to the Meat Crime.

Three years after it first aired on Netflix, that burst of domestic mayhem still has the power to shock; it’s one of the few moments in the Terrace House saga where the communal backbone wobbles. But it doesn’t break—not even close. With the help of Minori’s sister and a well-timed batch of Valentine’s cookies, Uchi and Minori patch things up and leave the show a couple. Like virtually every resident that has passed through the halls of Terrace House—even the feckless Yuudai—they are sent off with a proper meal.

If their Instagram accounts are any indication, the show’s former cast members still do this from time to time, meeting in Tokyo bars for food, beer and friendship. With the obvious caveat that these are reality performers, skillfully crafting their personal brands, they continue to project the authentic sense that life on Terrace House was nourishing; that for them as much as us at home, it was more than empty calories.

That’s not how most of us perceive reality television. That’s not how I perceived it before I watched this show. I saw the genre much as forty London-area women did in a 2008 study by British media scholars: when asked to describe their feelings while watching shows like Big Brother and Extreme Makeover, the most prominent phrase in their transcripts was “sad.” They used the word in its melancholic sense but also in the judgmental way we’ve been hearing it under Trump. The people on screen seemed pathetic to them: sad with an exclamation point.

As Terrace House wraps up this winter, I’m shedding that judgment and cynicism. I’m embracing the sort of buoyant, earnest sentiment you see on New Age social media. #TerraceHouse makes me feel #gratitude. The #MeatCrime makes me feel #blessed. When the last cast members leave the throbbing quiet of the house in Karuizawa, I will feel as Tsubasa did during one of this season’s hankie-ravaging farewells: “I’m so glad to have met you all.”