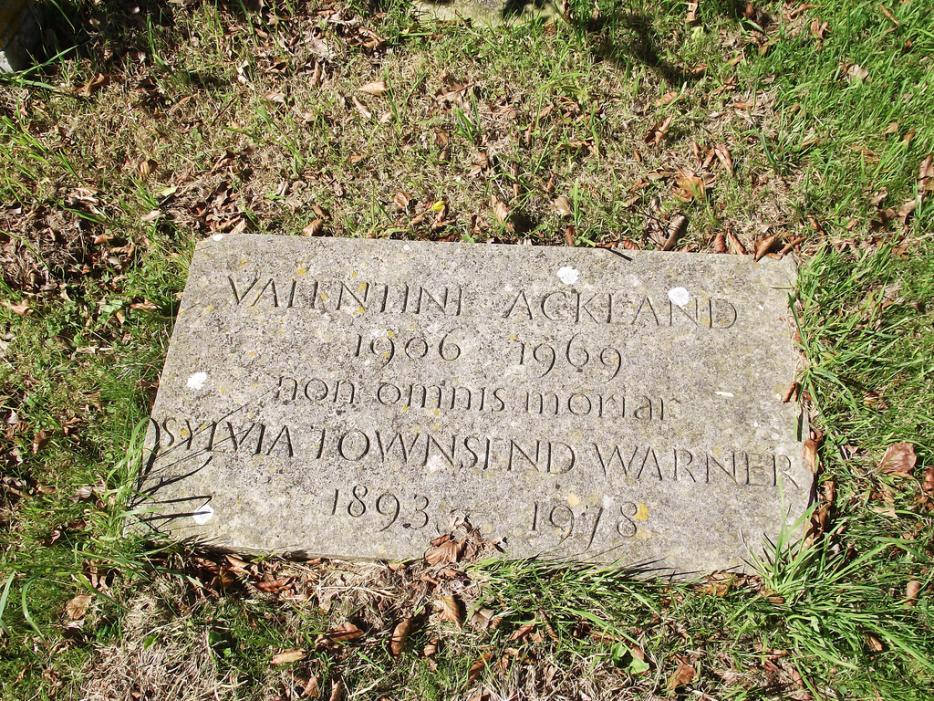

In the early 1920s, Sylvia Townsend Warner published her hugely successful first novel, Lolly Willowes. The writer spent much of her time in London, but at the suggestion of Stephen Tomlin, who later became part of the Bloomsbury Group, she went to Chaldon Herring in Dorset to visit the writer Theodore Powys. Powys and his self-made literary enclave attracted a variety of poets, writers and artists to the area. Warner found herself enchanted with Dorset’s rural landscapes, coastal views and small-town solitude and grew particularly fond of visiting Powys and his family.

One evening at the Powys home, Warner met Valentine Ackland.

Warner was transfixed, but not necessarily impressed, by Ackland’s slender figure and her self-assured demeanour. In one of her diaries, Warner describes Ackland as an “aloof unicorn” and writes that Ackland’s presence, and their strained conversation, made her feel uncomfortable. Warner assumed an atrabilious disposition toward Ackland and the two women retained an almost suspicious and distant friendship.

In 1930, during a walk around Chaldon Herring with a group of friends that included Ackland, someone pointed out a small house and suggested that Warner might like to buy it. It was decided that Ackland, who was at that time without a proper home, would use the house as temporary accommodation. Warner bought the house for £90 and returned to London whilst Ackland took up residence.

Ackland found Warner’s manner “abrasive” and describes her as “intolerably nervous” in her diaries. However, Ackland also admits to wanting to live with Warner. In one particular diary entry of Ackland’s, the distance between them begins to slip; Ackland admits to feeling “sad on waking to have lost the dream” because in the dream she had found Warner’s “eager and loving look,” which Ackland was sure she would never see on the “real woman.”

In September that year, Warner decided that she would spend a month or so in Dorset, whilst coming back and forth from London and maintaining her links with the city. Ackland, who also had commitments in London, would do the same. On their second Saturday together at the house in Chaldon, Ackland and Warner went for dinner. They returned home and lay in separate beds on either side of a partition wall. The calm evening was uninterrupted; aside from the soft murmur of the wind, a deep quiet spread out evenly across the village. In mellifluous tones, they began talking to one another in the dark. After a faint pause, Warner heard Ackland whisper into the night; “I sometimes think I am utterly unloved.” According to Warner’s diary, after several seconds, “the forsaken grave wail of her voice smote me, and had me up, and through the door, and at her bedside.” They spent the evening with one another and the next morning, they lay together on the Dorset downs “listening to the wind blowing over our happiness, and talking about torpedoes, and starting up at footsteps. It is so natural to be hunted, and intuitive. Feeling safe and respectable is much more of a strain.”

In an article for The Guardian, Sarah Waters writes that Warner’s work is “relatively under-appreciated.” Though there has been a revival in popularity in recent years, arising primarily from a recent investment by certain scholars to seriously re-examine Warner’s oeuvre, she still remains a neglected literary figure. Though Warner’s novels were well received amongst the audience of her day, they did not sustain a continued interest during the later twentieth century, ensuring that Warner fell out of the mainstream literary canon. Critics have speculated on the various reasons behind this, but more often than not, most attribute it to the fact that she was in an open lesbian relationship, held staunch Communist views and had retired to rural Dorset from London, ensuring she couldn’t maintain connections with a city that more easily promised visibility and success. I grew up less than eight miles from Chaldon and I was entirely oblivious to the literary connections that Warner had garnered here—I, like many people, had never heard of her.

Growing up in a small town in Dorset, London was the place that I made responsible for my future happiness. I spent my time at Sixth Form pouring everything I could into this future vision. Unlike Warner, I did not desire the quiet of the countryside. Instead, I sutured an impossible collection of overwrought expectations, lofty dreams and unobtainable aspirations onto this unknown city. London was where I was going to escape the insularity and single-mindedness of living in a small town in a rural county on the coast. It was where I could avoid spending my twenties dancing in grimy clubs on the seafront with the same people that I had gone to Brownies with. I moved to London in 2009 and allowed the transition to fulfil my teenage desire for anonymity and mystery.

For many years, living in London worked to counteract everything I had grown to hate in Dorset. I played the urban flaneur successfully, replete with Starbucks coffee and the same misty-eyed gaze of anyone who has discovered Proust for the first time. I went to university, read Judith Butler, drank cider in bottles bigger than my own head, spoke about The Fundamental Flaws of Neoliberalism with uncompromising yet naive confidence and spent chimerical nights in parks creating fleeting friendships with strangers. I was a living, breathing embodiment of the cliché I had longed for as a teenager.

When I was eighteen, I met the woman who would become my first girlfriend. She was obnoxiously confident and, almost instantly, I fell in love with the crooked angle of her fingers when she held a cigarette, the Polaroid pictures she showed me of living alone in Paris and how she would elusively disappear on nights out in a way I thought was implausibly cool. But it wasn’t until we had been friends for years that our relationship slowly changed. We would spend hours one summer lying on her bed talking, and many more hours lying awkwardly not quite knowing what to say. We would buy obscure Polish milk drinks from the local off licence and take long bus trips across London. We wrote each other notes late at night in our university library, sliding them tentatively across the plastic green desks, and slowly, we fell in love.

As our relationship progressed, returning home to Dorset became more difficult. My parents were less than pleased when I told them that I was moving in with my girlfriend. It was a shock for them; not only was I coming out, but I was committed to someone, committed enough to share a one bedroom flat with them, to share a bed and an IKEA cutlery set. For nearly a year, my father and I didn’t speak. While I think he found coming out reprehensible, his confusion and disapproval was simultaneously bound to his dislike of me living in London. My dad called it “my London lifestyle,” as if binding my sexuality to geographical exposure was a deadlock solution for trying to understand what was happening.

However, in many ways, there was a certain element of truth in his vitriol. It was easy to fall into the trap of steady and familiar London company. The ritual of staying in the same city and living out the same ordinary mornings and evenings became a reward; proof of something that belonged solely to me, an evidentiary footprint of a life that I had built for myself. London was where I was safe and respectable. The relationship with my father remained strained and we grew further apart. As each family occasion loomed on the horizon, the prospect of returning home was considerably more alienating.

Queer theorist Sara Ahmed writes that “as a structure of feeling, alienation is an intense burning presence; it is a feeling that takes place before others, from whom one is alienated, and can feel like a weight that both holds you down and keeps you apart.” In this sense, alienation presents a gauzelike cover across the world: displaying to you that which is there but which you don’t have access to. In London, it was easier to move smoothly in the world, and without friction: home was resistant to me. In the psychic landscape within which we wrap geography, something was always lost when I left London.

Outlining this interior struggle emphasizes the extent to which my own narrative is typical of the urban “coming out” stereotype; where it is the isolation of a small village in the middle of nowhere that one seeks to escape in favor of the promise of a bright city of acceptance and freedom.

The relative invisibility of cultural and literary representations of queer rural life further fractures this alienation. Queer theorist Jack Halberstam argues, “queers from rural settings are not well represented in the literature that has been so much a hallmark of twentieth century gay identity.” When I was growing up in Dorset, models of recognizable queer possibility were fundamentally invisible. The only books or films I encountered as a teenager explored what John Howard dubs the “gay migration narrative.” That is, books which examined how “rural and small-town queer life is generally mythologized by urban queers as sad and lonely, or else rural queers might be thought of as ‘stuck’ in a place that they would leave if only they could.” These references presented the city as the only viable alternative—the urban landscape was an obligatory rite of passage to ensure validity and future happiness. In the city, you are free and fabulous and comfortably surrounded by the tolerance of like-minded people; you are allowed to assimilate yourself into a world that wants you. In the countryside, you are melancholy, lonely and persecuted by people who refuse to accept you.

Halberstam argues that the story of coming out tends to function as a meteronormative story of migration from “country” to “town,” within which the subject moves to a place of tolerance after enduring life in a place of suspicion, persecution and secrecy. According to Halberstam, the idea that the individual must move from the rural to the urban ensures that the coming out narrative is constructed as mandatory. Queerness means deploying energy. It is never enough to just show up. Instead it is necessary to consistently forge spaces for yourself. Any struggle to try to accommodate yourself within an environment is a blind recognition of what it means not to fit in. Making yourself comfortable is socially necessary—in metropolitan centres and outside of them.

Though I loved my life in London, I began to consider the possibility of moving home. I needed to create for myself the cultural map that I didn’t have growing up, to forge a queer identity at home that felt viable. The binary between living out a queer/city experience and the heteronormative/country identity was only as pervasive as I allowed it to be. What happens when we return to the places that we once thought were suspicious of us, to the places that we had kept secrets from? What stories, people and objects do we rely on to figure ourselves as visible? When my relationship, which had anchored my time in London, ended, there seemed like no better time to find out.

A few days before moving home, I spent the day in a park with an old friend. It was blisteringly hot, and we were both repetitively applying viscous pools of sun cream to our arms and backs. I told her that I would be moving home to Dorset for a while and that my prescient feelings of anxiety around this transition were beginning to surface. “It won’t be for long,” she reassured me. I nodded my head in agreement but felt old feelings of tension and alienation bubbling furtively beneath the surface. My friend assured me that she felt the same whenever she went home; “I don’t think I make sense there—I am somehow out of context,” she said.

Whenever I go home to Dorset, even if this is just for a few days, there is a disconnect with my surroundings, with the environment, with my family and the people living there; as if perhaps, my life in London were a tale of local apocrypha that I couldn’t now allow myself to believe. When I first told my mum that I would be coming home, she was taken aback by my palpable concern. Almost automatically, I informed her that I don't feel I have a community at home. I had never even thought about really having a community, let alone lacking one. But admitting this, I suddenly understood why I feel somehow incomprehensible in my hometown. Moving to London had allowed me to exist within environments that validate queer lives, where I was offered an opportunity to move as part of a community and find spaces that explicitly celebrated identities that were never modelled for me as an adolescent growing up in a rural environment. Over the past decade or so, I haven’t really returned to Dorset for fear of losing everything that I’d taken so long to find. The return meant that everything I had fought for could so easily slide out of grip.

On one of my last afternoons in London, as I sat surrounded by cardboard boxes and piles of clothes, I found myself frantically scouring Dorset community notice boards for menial jobs, local art exhibitions and any activity that might keep me from falling into what felt like the imminent boredom and loneliness of returning to my childhood home. On the Dorset County Museum website under the Writers’ Dorset section, there was a small paragraph that detailed how “Twentieth century authors like Sylvia Townsend Warner and the Powys family took inspiration from the Dorset landscape and locality.” Almost instinctively, I felt drawn to Warner. I began buying biographies and diaries, spending the height of summer immersed in academic articles and collections of letters. Warner became a secret that I pursued. As Waters wrote, the fact that Warner is under-appreciated “baffles, frustrates and, I think, secretly pleases her admirers, for she's the kind of novelist who inspires an intense sense of ownership in her fans.”

This conspiratorial sense of ownership became inescapable as I prepared to leave London; I learned that Warner ran a book lending service in Dorset. I found a description of a matchbox that Warner had received from a friend—she loved the matchbox simply because she had never before received one. I listened to the falling, prosodic cadence of her calm voice as she read one of her poems, first written and recorded in 1938. I spent long, distracted hours in the British Library scrolling through pictures, studying her short curly black hair, her round spectacles, the cigarette that she holds delicately in her hand in one photograph, or the cat languishing in the sun across her knees in another. I obsessively scrolled through Google Images, finding pictures of her that I saved to the ever-growing landscape of my desktop. I re-read her descriptions of the willow-like catkin trees, that hang like “suspended hail; glistening, and pearl grey” and I revelled in her writing of a February afternoon when the Dorset landscape was a “pale earth” with “pale honey-coloured trees and an immense sun-lit purple cloud tattered with blue and wearing a rainbow.” I immersed myself in Warner’s Dorset from London, taking hold of it, as though it was somehow my own.

When I finally left London, I visited the Dorset County Museum with my eight-year-old sister. We cradled old sepia photographs of Warner like soft, smooth pebbles in our hands. The photographs depict Warner and Ackland where, leagues apart from the conservative, heteronormative standard of the 1930s, they lived together openly in Dorset. There are other pictures of Ackland and Warner on the Internet; Ackland is dressed in jodhpurs and carries a gun—hair slicked back, wearing a cravat and smoking a cigarette. They are rarely pictured together. But I can tell that in many of the pictures of Warner, Ackland is holding the camera. The softness in Warner’s eyes spools outwards, suggesting that someone she loves frames the picture.

Acknowledging Warner and Ackland’s past presence in Dorset was a secret talisman as I returned to the enclaves of my small rural town. Warner became the vanguard of some viable, rural queer life that I urgently hooked onto. Orientating myself towards what felt like a tangible history of queer, non-normative living, a sudden safety and calm washed over me. Out of context and feeling like I was losing my bearings by moving home, Warner was an object of hope. In Queer Phenomenology, Ahmed writes that “if we know where we are when we turn this way or that, then we are orientated. […] To be orientated is to be turned toward certain objects, those that help us find our way.” Warner’s archives, photographs and books were the secret, queer objects that orientated me home; the decision to move away from London became far easier knowing that there was a path that had already been taken by a woman that had seemed to find a semblance of happiness and acceptance in an environment where that always felt impossible.

Moving back to Dorset, it became clear that coming out is often also bound to spatial and geographic terrain—what might it mean to come out to myself in a place where I had never really felt queer? Leading with Warner’s life in my hands became a strange and secret model of possibility, a distinct means to become closer to my home. In many ways, I was returning with Warner, whilst also returning to her: to live through her.

Much literature that has offered representations of queer life has informed us that rural environments oppress the queer, whereas in the metropolis queers thrive. It is that strain of safety, especially for those further marginalized or persecuted by race, socioeconomic status, gender or age, which so often defines migration to urban centres. Yet, for Warner, it was Dorset where she was most at home. According to critic David Bell, so often the queer countryside is figured as either “hostile” or “idyllic,” whereby extreme characterizations often come to define the rural experience. The narrative of Ackland and Warner, however, is a story where rural queerness isn’t necessarily figured as lonely or hopeless. Similarly, it isn’t necessarily characterized as blissful and happy, without skirmish, social judgement or relational blemish. However, I found some hope in the modest banality of their life in Dorset, which made it clear that by returning home, life there wasn’t backward, impossible and hostile, nor was it was straightforwardly a bucolic utopia of queer acceptance.

*

The first evening back at home, I lay on a mattress on the floor and argued with my ex-girlfriend over the phone, crying myself into a semi somnambulant state only to be woken at 6 a.m. by the sound of an incensed wasp caught in the folds of the curtains. I dressed quickly, sent a text message I probably shouldn't have sent, and broke into a cool Sunday morning. I began cycling through the village of Upwey and didn't quite hit Martinstown before I decided to make my way to Dorchester. Having missed breakfast, the climbs were steep and arduous. Swapping the verdant patchwork downs of Martinstown, Mallards Green gave way to the sterile toy town of Poundbury and in the distance emerged a McDonald’s that I recognized as the spot lit breakfast stop from long car journeys taken as a child. Hungry and tired and seated on a yellow plastic high stool at a burnished metal table, I looked at the map on my phone. In block capitals, Hardy’s Country presented itself on the screen. My fingers pinched and dragged the virtual patch of land into focus; I decided I would find the home Warner shared with Valentine, in Frome Vauchurch, which lies eight or so miles north west of Dorchester.

Having spent several months attending the Second International Congress of Writers in Defence of Culture in Spain, Warner and Ackland found themselves back at their home of Chaldon Herring in Dorset on the 16th July 1937. Both women were exuberant, consumed with ideas “for articles and propaganda.” Yet this would be the last time that they would return to Chaldon. According to Claire Harman, the women, who were partners in love, writing and politics, saw a small advert in the local paper for a small house to rent on the outskirts of Maiden Newton. Warner and Ackland moved from their infamously damp and dank habitude at 24 West Chaldon, in East Dorset, on the 23 August 1937, taking up residency in Mrs West’s house by the River Frome, in Maiden Newton, Dorset.

Seventy-nine years later and on the dawn of August’s arrival, I strapped my helmet to my head. I felt conspicuous as I downed the coffee out of my McDonalds cup, apologizing profusely to families preparing for Sunday football because my bike was in the way of the automated door. Revelling in the magical perversity of the names of small Dorset country lanes, I took several wrong turns before I found myself on a small country track, headed for Brandon Peverell. On the long road, the air pushed past my face, drying the dampening hair under my helmet. With no one around, I shouted into the air. I hadn’t seen a car for the last mile. I shouted again, with the momentum of my bike pushing me forward into the early morning.

Calm solitude swarmed around me as the wind washed across my face. The monotonous, empty iterations of similar roads and countless white rolling hills had always instilled a deep isolation in the past; an easy metaphor for the lonely banality of my teenage years. But for the first time, in a place that spoke of past loneliness and forceful distance from who I thought I was, a quiet stillness had momentarily taken me. I was boundless, moving past the anxiety of the months previous, cycling faster across the Dorset downs across low hills with flecks of stone spurring underneath my wheels.

As I moved across the dust-white, chalk landscape, Sylvia’s home and the knowledge of her life here were a reminder of something that I so desired to know could exist. She was the vehicle for beginning to belong: a cathartic reassurance of self-viability. Sometimes we need to live through the presence of someone else to remind us of who we are. She reminded me that I could create an identity for myself here, outside of one that had been defined solely by living in the city. Moving through the hills, I could challenge the rural environment where I had never felt I had belonged. In many ways, I needed to return home to come out to my home.

In a poem, Ackland writes:

Space is invisible waves. In leaves of trees/ Space-water rustles, and the sway of these/ Is only movement of seawater under tide/ In restless sway and swing from side to side/While in the invisible air and in the sky/ Spirits like deep-sea fishes are sweeping by/ And the wind is no wind but a fast-flowing current of tide/ And the spirits are blown and driven and cannot abide.

Whilst space in this poem is figured as invisible, it also remains forceful; it has the powerful potential to move and alter—the invisible strength to shape you. However, space is also transversal, continual, and perhaps even recurrently revisable in the “restless sway and swing from side to side.” It is Ackland’s account of space that seems like fertile terrain for rethinking the geographical, spatial contours of queerness. The environment I grew up in did not seem revisable. It felt like it had shaped me and that I needed to get away from it in order to shake its grip.

However, part of what has always been so compelling about queerness is the potential it offers to create alternatives modes of being, doing and living. There is such unprecedented joy to sidestepping the seemingly binding structures that you have simply been given and not asked for. Believing that the city is the only place of queer self-intelligibility upholds the fact that I am somehow in the closet in my rural home. I spent a long time allowing this idea to sediment. When many cultural and social representations of coming-out tales portray the urban as the only platform for queer visibility, it is easy to allow this to become the dominant narrative.

Ackland’s anamorphic concept of space seems like the fertile terrain for queering the dominant narratives of queer visibility; for troubling the spaces that are prescribed as mandatory conduits for assimilation and acceptance. Whilst I don’t want to deny that there are still complexities and dangers for many queer folk in rural environments, it becomes all the more necessary to remember that there are always local, queer stories at work. Establishing that the rural and the urban are somehow mutually exclusive, or that to find one, you might need to escape the other, it becomes abundantly clear that these seemingly paradoxical positions, which bolster the conventional queer migration narrative, might themselves, need queering.