“This book you better like may not be exactly what you expect,” said Alexander MacLoeod at the Nova Scotia launch of Christy Ann Conlin’s The Memento, a complex amalgam of realism, gothic sensibilities, fairy tale and dream-space. A ghostly coming-of-age story for outliers, it nods to a three hundred year legacy of uncanny literary writings—the likes of Nathanial Hawthorne, Marilynne Robinson, Horace Walpole, Ann Radcliffe, Wilkie Collins, Shirley Jackson and Henry James. At the same time it blends the contemporary with the old world, evoking the work of Alistair MacLeod, Ernest Buckler and William Faulkner. It is both harsh and tender, encoding a deep, dark intimacy that makes it both defiantly personal and singular.

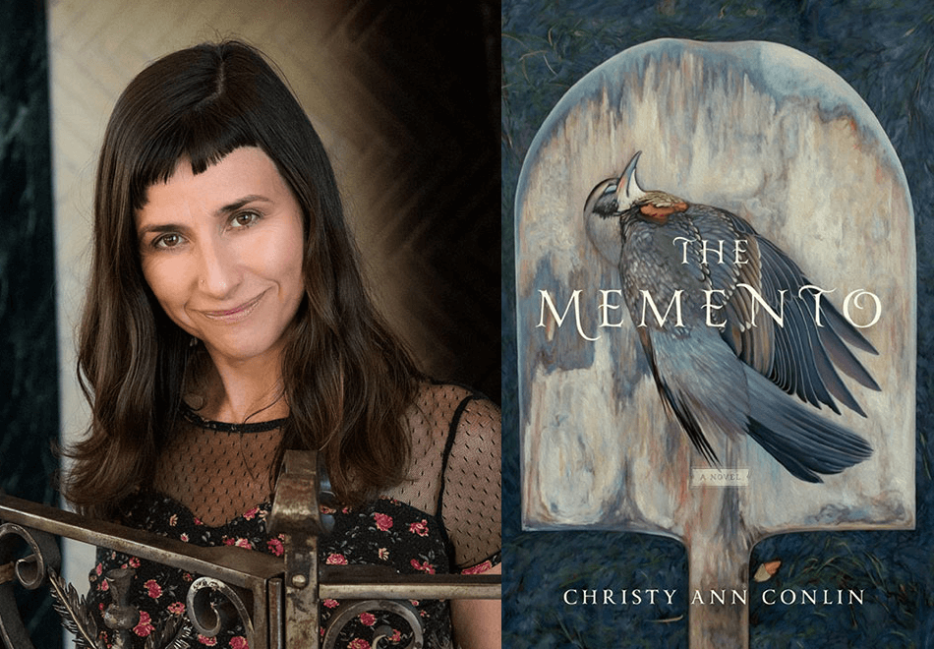

Conlin, who is the author of three books as well as several works of fiction and non-fiction, and I settled into the quaint Victorian salon of a charming shipwright’s home in Kingsport, Nova Scotia, near her home in Wolfville, to have a lengthy chat about The Memento. As we spoke, the fog burnt off the Bay of Fundy, the tidal bore did its grandiose thing, and what wind there was got the old bones of the house creaking—ideal pathetic fallacy for talk of ghosts, and insidious secrets, and all things gothic.

Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer: Your work—Heave, Dead Time, and now The Memento—is concerned with mental health, addiction, women, and the way family distorts us but also makes us who we are. The liminal space of adolescence, and its particular transformative nature, are also factors. I wonder if there is a connection in your mind to these realist impulses and the enchanted spaces you conjure in The Memento?

Christy Ann Conlin: I am interested in how we, as women and men, are shaped by family and society, and how we react to and against this, both in adolescence and then as young adults. The Memento takes place in two parts, when Fancy Mosher, the narrator, is twelve, and then twenty-four years old, two key developmental life stages, transitional stages in life, and in brain development. Our perception of the world changes as we age. When we experience trauma, then depression, anxiety and addiction become our companions, reactions against the horror of being oppressed which take on a life of their own.

When we speak of young women, I’m interested in how we internalize sexism, and how this can distort and pervert identity as we pass through these developmental milestones.

And I wanted to explore realism as it collides with fantasy. Fantasy and imagination are an expected part of a child’s life, and then, in adulthood, these same areas of play can become something more pathological when it serves as a means of escape and avoidance. The Memento is a genre-bending book, evoking the old world novels of Jane Austen, the Brontë sisters, and Edith Wharton, but pushing it to another level with supernatural elements and a contemporary thread. Jane Austen scholar Sarah Emsley said to me that in The Memento the Parker family’s grand estate, Petal’s End, evokes the world of Downton Abbey or Northanger Abbey, and the young heroine Fancy Mosher brings to mind Jane Austen’s Catherine Morland. Catherine Morland imagines with delight all the gothic horrors that might await her at Northanger Abbey but for Fancy Mosher, the horrors unfold.

Actually, that sounds a bit unnerving, when you put it like that. How was the experience of dabbling in horror on this level for you?

It was fascinating playing with a real world which is enchanted, so to speak, one which ensnares all who enter in a sense of timelessness. Enchantment is such a delicate and feminine word, so unsuspecting. But it is this aspect of the female psyche I find most captivating, that we enchant and bewitch and yet those very words mask the peril of being captured in a spell, a spell cast by family, at such a tender and impressionable time as adolescence.

Much of my work is driven by this idea of nurture and nature, that we are born with a particular personality and temperament, and then we are shaped by how we are raised at the hearth (in the family), in the public square (society), and at the altar (emotional and spiritual experiences and rituals). Mary Pipher writes in her book Reviving Ophelia: Saving the Selves of Adolescent Girls of the transformation of her cousin, who enters adolescence a tree-climbing exuberant tomboy and comes out the other side wearing lipstick, teetering on high heels, the tomboy banished. Adolescence is a time where girls often first encounter sexual objectification, and the idea they exist for the pleasure of others. The socialization process intensifies and we become strangers to ourselves. We lose control over our very bodies and the cloak of childhood falls to our feet.

During my research for The Memento, I was captivated by the old saying that particular inclinations, temperaments, abilities, and even personalities are born into us. Fancy Mosher, Jenny and Pomeline Parker all have particular abilities but it is their upbringing and environment, which shapes how these abilities manifest.

One element I aimed to show was the vulnerability and subsequent abuse and torment of girls and women, the marginalized across gender and class lines. The ghosts in The Memento symbolize a subversive power, a fierce and unholy railing against those who prey upon the weak and defenceless. These phantoms are a powerful juxtaposition to the helplessness of the living characters—unearthly voices for those who are oppressed. Both harbingers of doom and redemption, these supernatural forces refuse to play by the rules. They creepily redefine the game using the very objects in life.

Please speak more about the mythic elements of The Memento. It seems to me the novel shimmers with an undercurrent of something larger than itself—a kind of knowing. In some way, the story feels like it was always there, if that makes sense. The reader has the impression they have walked into something like a dream that’s been playing all along. How does myth operate for you, as you write? As you edit?

Yes, it does make sense to me. It’s a high compliment you experienced the story this way. I think these stories, which travel through time, serve as warnings and as beacons of hope, sometimes both. Myths, legends, fairy tales—these stories feel as though they are perpetually in play, and that we can tap into them at any time just through the telling or reading of the story. I really played with this with the place names in the book, Evermore, the garden, the Woodcutter’s Cottage, Petal’s End, The Water House—names that evoke the perpetual realms in fairy tales and legends.

Whenever I read Greek myths to my sons, and certainly there is nothing which combines harshness and magic more than Greek mythology, it’s as though we enter into dream or fantasy which weaves through time, and is constantly rediscovered, like a dream, as you call it, which never ends. The reader can enter into the dream world, which continually loops. This is the domain of the oral tradition, where stories live in the telling—we breathe life into myths through speaking the words. We have largely lost touch with the oral tradition in our culture, although it does seem to survive out in the open in songs and music.

Ghost stories in particular have an age-old endurance throughout the world, and throughout time. My parents always listened to the radio show called Ideas on CBC Radio and I remember when I was quite young hearing a conversation with guests Margaret Atwood, Graham Gibson and David Cronenberg where they chatted about ghostly things, and their role in society and art. Margaret Atwood had this great line—“The ghost story is a way of examining the self coming to terms with the self”—and I think this is true on an individual and societal level, and it’s why we have our own personal ghost stories, and ones we share as a community and as a culture; we are in a constant state of coming to terms with ourselves, who we were, what we are, and what we are becoming.

So you felt you were self-examining? That’s interesting to me, given the gothic elements.

Honestly, at the beginning of my work on The Memento, I felt as though I was remembering an old, old story from the land, which I only had pieces of, as though parts had been told to me as a child, and that I had overheard others whispered by the fire. So I come by these beliefs honestly [laughs]. My mother always told me to never wear a dead lady’s apron and my grandmother always said to exercise caution when drinking out of a dead man’s cup for it might not be as empty as it looked. My grandmother had been a nurse in private homes in the 1930s, and stood vigil by many deathbeds, administering last sips of water or weak tea and whiskey to the dying. These objects were powerful symbols of the people they had belonged to, mementos left behind, an embodiment of the person who had died, and the grief also left behind in death. Using such mementos could invoke their spirit, for better or for worse. I needed to take extra care, they both said, for I was the only girl born in a generation, and this meant I had a special sensitivity for these things—the spirits would seek me out. And then I inherited my grandmother’s china tea set and thus the story for The Memento began to brew. It is no small wonder I have an affinity for ghost stories!

But certainly the weight and importance of ghost stories has been diminished and shoved to the side. We giggle at ghost stories, and dismiss what might have inspired awe, caution, reference or respect in earlier generations. We embrace horror as a fun outlet, not as one of warning or guidance. In Inuit culture, First Nations culture, in Asia, there is far more respect for the old stories and legends, and for the concept of ghosts and phantoms. I taught ESL in Korea and it was there I first encountered Korean and Japanese ghost stories. What was interesting to me was the role of ancestor worship in these cultures, the belief that once a year spirits come to life, a fundamental respect for afterlife. It seemed to me what permeates this is the conviction that what you do becomes a part of you, so if you break a moral code and a sacred set of values, you’ll be haunted by this for the rest of your life and beyond. And so will your family.

In the first few drafts of the novel I was exploring the realistic elements of the story, the setting and the characters, even though the novel always had this pull of what you call an undercurrent of a more mythical world. It was a process of uncovering it, if you will. It was very much as though I was recalling pieces of fairy tale and myth, unearthing a story. But before I could let this, so to speak, sweep the story away, it was critical to understand the story that takes place in the common world. Once this foundation was laid, then I was able to let the supernatural aspect weave through, combining elements of a gothic ghost story, and magic realism. I wanted that juxtaposition of a harsh and closed society where the marginalised and disenfranchised are so powerless, with the supernatural elements rising out of their anger and persecution.

And how do you, then, manipulate these elements? How do these elements converge in self-examination?

At the core of what influenced the book lies my experience of being sexually assaulted when I was eight and then later in my early twenties when I was in rehab, both times being powerless to do a thing. And for years thinking I had done something wrong. Part of this book was looking at how distorted memories do haunt and torment us, and how we mutate our own memories to both hide our secrets, but to rationalize and find explanations. For a child there is no rational explanation for sexual abuse. It is only that a monster has somehow been summoned…but by whom? In The Memento, Jenny, the unlikely anti-heroine, follows her own religion, and through this becomes impervious to adult efforts to manipulate and control her. She is the only one who sees clearly, and even her love for her grandmother does not sway her from her values. It is Jenny, a quintessential grotesque character, who wipes away all distortion and lies. In the possession of an almost demonic clarity and truthfulness, she holds all to account. Jenny is without mercy. It is Fancy who holds the mercy for them all, in her mementos.

There has, of course, been much talk of sexual assault and much discussion of the contours of feminism in media these days. It’s been unavoidable and difficult for many people, myself included. Is there an analogy to be made between the setting of your novel—a colonial ruins—and this story of violation, generally?

In my novel, young girls are also robbed of any sense of personal agency until they finally rebel. They search for their own language and moral code. And when they do, it is a code of both mercy and vengeance, which rises forth from the desecration of their bodies and innocence.

I think much of the trouble begins when men judge a woman’s response to assault from a male perspective, at how they would respond if it happened to them, even though it’s impossible to do this as men are governed by entirely different expectations and allowances. And this lies at the heart of all oppression, when we have a particular moral code and set of values and privileges and assume it’s the same for all. Sexual objectification shapes girls, as they approach womanhood. We learn how to keep our heads down. All around are signs which remind us of a prescribed role, which is one of compliance and conformity—or else. There is so much talk now of what young women wear, and how it distracts young men from their studies. It’s shocking the conversation is not about why young men can’t control themselves, that women are the object of temptation, and the moral judgement, which then ensues. But worthy of note, as well, is the message we send to young women, that being sexy and attractive is valued above all else. And yet we then hold them responsible for the expectations heaved upon them to start with.

The Rehtaeh Parsons case in Nova Scotia has thrown light on just how regressive society is when it comes to women. We’ve seen just how harshly a community judges a woman who doesn’t behave in prescribed ladylike behaviour. I was shocked by how many people I knew felt Ms. Parsons deserved what happened to her, that the young men were tempted and she created the situation herself. Excuses were so quickly made for young men. Even if people felt what they did was wrong, there was still a sense that boys will be boys and girls will be sluts. And sluts get what is coming to them.

Which brings me, peculiarly, back to fairy tales, and the way you play with enchanted tropes. It seems to me that the fairy tale in its brutal simplicity can get at some nugget of violent truth that the novel necessarily must walk a more circuitous path toward. I’m thinking specifically of the use you make of portraiture, but there are weird portals in the novel, too. The enchanted pond and the room one is forbidden to enter come to mind. The uncanny—the defamiliarised everyday space—is made much use of in this novel. Do you think that we convene on the fairy tale and on fairy tale tropes because they are a shorthand, or because they tell it slant, or…?

Throughout history we have been embedding story, hiding if you will, violent and horrifying truths, stories told and then retold, truths that become stories that, in turn, become mythicized. I think this goes back to the way we are as children, where we either hide from, or interpret the horrors we experience. The noise in the night becomes a demon. The rustle under the bed, a monster. The closed closet door in the midnight bedroom becomes either a portal to hell or a container of a devilish creature awakened by the moonlight on the floor. This is how we make sense of abuse and exploitation when we are small and are not able to intellectually comprehend or logically explain what has happened.

When we look back at the origins of the fairy tales the Brothers Grimm transcribed from the oral tradition, we see their origins as stories told to the children of the upper classes by peasants, those suffering, oppressed, metaphors for anger, violence, injustice. Lordy, the earliest Little Red Riding Hood (written by Charles Perrault) has her stripping, getting naked in bed with the Big Bad Wolf and he EATS her. Those were the bedtime stories told by the French. It’s no wonder there was a revolution! So, all that to say, that fairy tales do have at their heart a violent truth from which comes a fantasy spun to contain that violence, to hold and contain this darkness at the centre. They allow us to loop toward a truth. Horror in art draws us because it does this for us, offers us a safe way to confront the terror and violence in our lives, in our history. We live with a legacy of great violence and fear.

The Memento is strewn with fairy tale images and metaphor. Both adults and children tell ghost stories and legends. The children fully believe and the adults, while skeptics, are still wary of the truths, which lurk behind these tales, stories that become legacy. The world of The Memento contains many symbolic settings: a forbidden room, the Annex, the enchanted lily pond, the magical garden, the enchanted forest, the woodcutter’s house, the water house where the botanical potions are made, the graveyard, a mystical island, a grand creaking house. All of these are places of wonder and places of danger, where magic lies, where you enter at your own risk. As I’ve mentioned earlier, the book takes place when the main characters are twelve and twenty-four. When they are children and they forge ahead into the forbidden areas, they awake a dark presence, which follows them for twelve years. As adults they enter the same forbidden places but this time knowing.

The personal is encoded, then, into the safe package of story?

My interest in working with fairy tales and supernatural elements came out of my own childhood of creating fantastical stories to make sense of the traumatic experiences I had as a child. My father had a life long struggle with mental health issues, alcoholism and drug addiction. It made for some very sad and challenging times. When I was very little I had an imaginary friend named, of all things, Cursalina. My mother found it unnerving. My memories of her are vague but I do remember wondering why she stopped coming. Perhaps this was a threshold in my childhood I stepped over, where I could no longer project the emotional disarray and confusion and terror of my childhood into story, when I was then abandoned by my magical guide and protectress. I know she originally appeared when I was angry and afraid. She was never afraid. When I was about ten a friend told me that imaginary friends are actually the spirits of dead children who come because they sense your aloneness and suffering. I was old enough to understand the implications and young enough to find that both terrifying and exciting.

In my rather challenging childhood, making up fairy-tale-like stories gave a narrative and a shape to the pain and incomprehensibility of what I was experiencing and living. The stories were worlds I could escape to, where I understood the rules, and the fears. When I was eight, I went to a park with my friend who was also eight, and we brought her two-year-old sister with us. Why on earth we were allowed to go to a park alone, and with a toddler, I have no idea but it was the seventies and things were different. It was a hot June day and we were wearing bikinis. The sky was an intense blue and to this day I remember how sweet the rose bushes smelled. We felt so grown up, that is until we got to the park, and two young men appeared. They let the toddler go, but my friend and I, who, despite our bikinis, were also little girls, were assaulted in the playground in the park. To this day I cannot go down a slide or sit on a swing without remembering the violation and torture we endured in this supposed place of carefree innocence and lighthearted fun.

And it was an impossibly beautiful summer day, with a vivid blue sky and birds singing. It was as though we had tumbled into an old world fairy tale where the woodsman didn’t come to save us from the big bad wolf but came and joined him.

When they finally let us go, my friend and I swore to each other we would never tell. We ran back to her house and her mother screamed at us for letting the two year old wander home alone unattended. And still we said nothing. I couldn’t keep that vow though and did try to tell an adult who told me I must be imagining things. I think the biggest trauma then was realizing that adults wanted it to be a fantasy, that such a thing could happen was too horrifying for them to hear. So for me, it was a moment where reality felt pushed into the land of fantasy. But I knew it had happened, and that the fantasy was adults living in a world where they could not see it. This was when they muttered words which seemed to work as spells, to preserve this false sense of security in a world where they actually felt as powerless as we did as screaming little girls by the teeter-totter in the shade of the big tree.

Yes, shade and shadows, the things of nightmares. When I did try to talk to adults about this, I felt as though I had broken our vow, and we were then cursed. She had kept the silence but I had not, and had unleashed demons who would hound us. I moved away and we lost touch, but you never lose touch with that sort of childhood violation. It becomes a horror story which plays over and over again, until you make your peace, evoke a spirit far stronger, which for me has been that of forgiveness and hope, one of survival and triumph. Even in recovery, fairy tale and hero mythology is at play, where we finally heal when we banish the demons. Maybe there is a courage which rises up from having walked through the deep dark woods and making it to the other side.

I did not intentionally set out to write a story which explored my own childhood abuse, and The Memento is not my personal story. But it is a broader exploration of, as I have said before, the exploitation of weak and vulnerable (in our society, women, children, the disabled and deformed, the poor and the marginalized) and how in unearthly ways they are resurrected and vindicated. The Brothers Grimm re-envisioned fairy tales with happy endings. I believe not in happy endings, but in endings where justice is served, and where peace is made, one way or another.