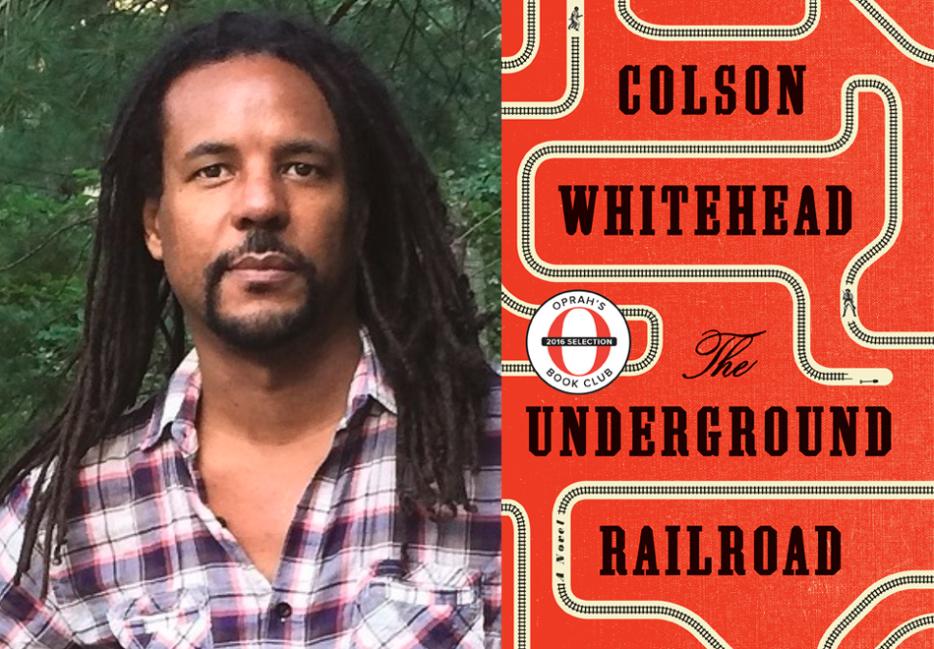

Colson Whitehead’s new novel, The Underground Railroad, tells the story of Cora, a girl born into slavery, as she escapes from the plantation with Caesar, a new friend and fellow escapee, while Ridgeway, a slave patroller, obsessively dogs her in pursuit as she makes her way along the titular tracks. Whitehead takes the slave narrative to new territory, however, by answering the question: what if the underground railroad was a real railroad?

Station masters offer help and guidance at stops along the way. Lumbly, a conductor on her first train, tells the pair that “[every] state is different. Each is a state of possibility, with its own customs and way of doing things. Moving through them, you’ll see the breadth of the country before you reach your final stop.“ Whitehead’s story takes Cora through several American states as each one grapples with slavery’s presence and legacy. And in each, she experiences that state of possibility—not just of what America is and what it could be, but also who she is and who she can be.

It is a beautiful, jarring and compelling story—no surprise that it has quickly become one of the most talked about books of the year. Among its many accolades, including making its way onto President Obama’s summer reading list, it’s an Oprah Book Club selection. It was illegal to teach slaves to read and those slaves who could risked their lives; in the novel, Cora values deeply the ability to read and learn. I can’t help but be struck that we’re in a moment in time in which a Black woman is such an influential player in the literary world.

I spoke with Colson Whitehead by phone.

*

Vicky Mochama: I want to start at the end of the book. In the acknowledgements, you cite Prince, Sonic Youth and David Bowie. What role did music play in writing this book?

Colson Whitehead: [laughs] I started writing fiction about twenty years ago. When I work I play a loop of my favourite 200 songs on a playlist. It goes from the Ramones to David Bowie to the Lounge Lizards. Whenever I finish a book and I get to the last day of writing the first draft and I only have two pages to go, I put on Purple Rain and Daydream Nation. That’s my ritual. Whenever I put those albums on back to back, I know I’m in the home stretch.

What was it like for you to this year lose those artists that were fundamental to your process?

I guess you never contemplate Bowie gone. And then I did the acknowledgements and Prince passed away. There’s always the music. It’s a great loss. When Bowie died, I played my children (who are two and eleven years old) loops of his old music videos. Now, when I take my son into bed, I have to play him “Silent Night” and “Ashes to Ashes” by David Bowie, so I end up singing it every day. One day he’ll ask what a junkie is because that’s one of the lines in “Ashes to Ashes,” and I’m not sure what I’ll say, but we’ll get there.

Talking of your process, when did you sit down and think you could actually write this book?

I had the idea sixteen years ago and didn’t feel ready. I came up with the premise of exploring that childhood notion that the underground railroad is an actual subway. I kept putting it off. I didn’t want to tackle the enormity of slavery. I didn’t feel emotionally ready and I didn’t feel mature enough as a person. As a writer, it seemed very daunting. Every couple years, I’d go back to my notes and think, “Am I ready?” and the answer was always, “No.” But finally, about two years ago, it seemed I was afraid of doing this book and it was time to confront why and just take the plunge.

What did you find out?

We walk around with different ideas of what slavery was, but to actually read the testimonials from former slaves and hundreds of slave narratives, there’s no escaping the brutality of the system and, in my case, what my ancestors went through. It was a consideration of who in my family didn’t make it out.

I think as Black writers there’s always a sense that we don’t want to talk about the things that are meant to define our communities. Did you have any doubts about writing a slavery book?

Mostly in terms of ability and wanting to do the idea justice. It had a lot of possibilities in the premise of the book, so I waited until I was ready. The hardest part was once I’d done the research and realized how many terrors I’d have to submit my protagonist and her friends to—that seemed very hard. The reality is that in the book she’s sixteen years old, and by that time she’s probably suffered some form of sexual assault or one of the terrors of slavery. So having to put everybody through the horrors of that first chapter was difficult to contemplate.

The book extends the childhood notion that the underground railroad is possibly a real railroad. I was talking to my sister about this and she said for a very long time, even as an adult, she thought there were real trains.

It’s a fairly common mistake that people make when they’re young. If you search for “the underground railroad” on Twitter, high school kids are making fun of friends, saying, “Sarah thinks the underground railroad is a real railroad smh.” The image is very powerful and informs our idea of how things work.

What was your research process for the book?

I tried to do enough research to get going. In this case, there are a few histories of the underground railroad. The one that I came to first that was most useful was called Bound for Canaan by Fergus Bordewich, and that was very comprehensive. And really, just slave narratives. There are the big ones: Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass—Harriet Jacobs, who spent seven years in an attic, informed the North Carolina section. The U.S. government during the Depression hired writers to get people back to work, and the writers interviewed former slaves: eighty-year-old, ninety-year-old people who’d been on the plantation when they were kids and teens. Some of the accounts are just three paragraphs and are about farming life. Some are ten pages long and contain someone’s whole biography. There’s hundreds and hundreds of them. I was able to get a log of details about people living in different plantations in Tennessee versus Georgia versus Florida, sugar versus cotton. It was my introduction to the variety of the slave experience. As a writer, it was just a really rich source of material.

How does it feel having done all this research in order to write the book and then to see people take issue with statements like Michelle Obama saying slaves built the White House?

I’m fairly well educated, and the true scope of the depravity of slavery was unknown to me. I hadn’t thought about it in a while. The research really opened my eyes. In terms of the reaction to Michelle Obama, I don’t think we teach the truth of slavery. I don’t think we teach in our schools a tenth of the reality. In general, we skip to the Civil War and Lincoln and then slavery was done. We don’t talk about Reconstruction or Jim Crow. We fast-forward to Brown V. Board of Education, which ended segregated schools; we go to Martin Luther King. In schools, we skip to the good parts. Most people are coming from a place of ignorance. But also, who wants to talk about their great-grandparents’ culpability? Who wants to talk about how their great-great-grandparents were abused? It’s a natural reaction to shy away from the true horror of it. I’m not excusing it, but it is a lot for the mind to handle on top of our ignorance and not wanting to think about the past.

Did you write this book to explore how you felt or understood slavery?

Not so much slavery, but slavery and American history and this character. I think all books are an exploration of the world in different ways and trying to figure out how the world works. The Underground Railroad, because of its structure, allowed me to talk about different aspects and phases in Black American history—whether it was the Tuskeegee syphilis experiments, which make an appearance, [or] the commonality of the immigrant experience and the despised other, whether you’re hated for your Blackness or your Irishness or your Italianness. Certain books allow me to discover how I feel about things and then there are other books that allow me to make sense of how the world has come to be what it is.

A couple of the characters express the idea that if God didn’t want the Africans to be slaves, then they wouldn’t be. I feel like that’s an idea you see currently in many different ways. Were there moments that you could see contemporary life reflecting things that you were writing in the book?

There’s a policy called Stop and Frisk in New York City which allowed any cop to stop anyone and on the barest pretext search them and check for ID. It’s had different names over the years. It’s an echo of early police enforcement during slave times—there was no police force, and the people who stepped in to keep order were the slave patrollers. They could stop a Black person, go into any Black person’s home—whether it was on the plantation or a free person’s house—and demand to see their papers. Those kinds of parallels aren’t hard to force into the book. The world was pretty racist 150 years ago and it’s pretty racist now.

One of the books that Caesar reads is actually a Gulliver’s Travels book. Was it intentional that the book would mirror that kind of a road trip?

When I first came up with the idea that each state would be a different state of possibility, the immediate comparison is Gulliver’s Travels. I’m not a Jonathan Swift fanatic but that structure became a convenient way to talk about the book with other people. It is an episodic adventure story in a certain kind of a way: it’s The Odyssey, Pilgrim’s Progress, Gulliver’s Travels, so that structure was an early decision I made and allowed me a lot of creative play.

The character of Ridgeway is reflective of an attitude held by poor whites—

—and rich whites. He’s a voice for the American philosophy of “might makes right,” “if you can keep it, it’s yours,” and, “if you can’t keep it, why not destroy it?” It’s an imperial philosophy that plays out around the world and in different phases of history even today.

At one point, he elaborates on his theory of the system, and as you’re listening to him explain it the logic starts to fall apart a bit, but he says, “It’s an imperative I have to refuse”—that imperative being to allow the system to break down. Is that at the heart of the difficulty of addressing racism now?

I think you want to preserve your power. If you talk to a lot of Trump supporters, they’re upset that people of colour and women are in power, and white men have lost their stranglehold on possibility. When you have something good going, you definitely want to protect it. That’s definitely what Ridgeway fears. That’s what people in contemporary America fear: what place they have in the future when the people they’ve subjugated for centuries are coming into their own.

So what do you envision when it come to America’s future in dealing with one of its original sins?

I think things improve and progress quite slowly. Certainly, I never thought we’d have a Black president. For most of my life, that seemed inconceivable. For some people, it seems inconceivable that we’ll have a female president. Growing up with Margaret Thatcher [laughs] it didn’t seem that impossible. I have two kids who don’t think it’s odd at all that we have a Black male president and a female candidate, so that is obviously an advancement. I can vote, I can publish; obviously, I’m not living under the yoke of slavery. Things improve slowly—not fast enough, because old systems die hard, but I certainly have the hope that my children and their generation are moving into a better world. Cora, when she takes that first fateful step off the plantation, believes that there’s a better world out there. If you don’t have hope, then why go on?