“Have you ever suicided yourself?”

This is Tom, who didn’t want to use his real name. He’s nine years old. We’re standing outside a corner shop in Kashechewan, a reserve of 1,800 in northern Ontario. He’s asking me. I wasn’t sure quite how to respond.

Tom pretends his hands are a noose and starts to strangle himself. Then he asks again: “Have you ever suicided yourself?”

“No,” I tell him.

“Why not?”

“Because I like life.”

“She has,” he says, pointing to the girl standing next to him. Kristal (also not her real name), 14, doesn’t look depressed. She doesn’t give off any obvious signs of someone who’s neglected or from an abusive home. Instead, everything about her seems handled with loving care. She’s wearing a purple checked jacket and jeans that fit her slim frame perfectly. It’s hard to stay clean in Kashechewan because of the unceasing dust from the unpaved roads, and yet her clothes are spotless.

She glances at Tom, frowning slightly. “No I haven’t,” she replies.

“Yes she has,” he adds.

As if to prove him wrong, Kristal rolls up her jacket and shows me her right arm. Four purple scars run its width, perpendicular to her veins. It’s cutting, not suicide.

The numbers are hard to determine—there’s been no formal study on cutting specifically—but it is estimated by those who work on the reserve that about one in four are addicted to self-harm. And it’s not just children who cut in Kashechewan—adults do it too.

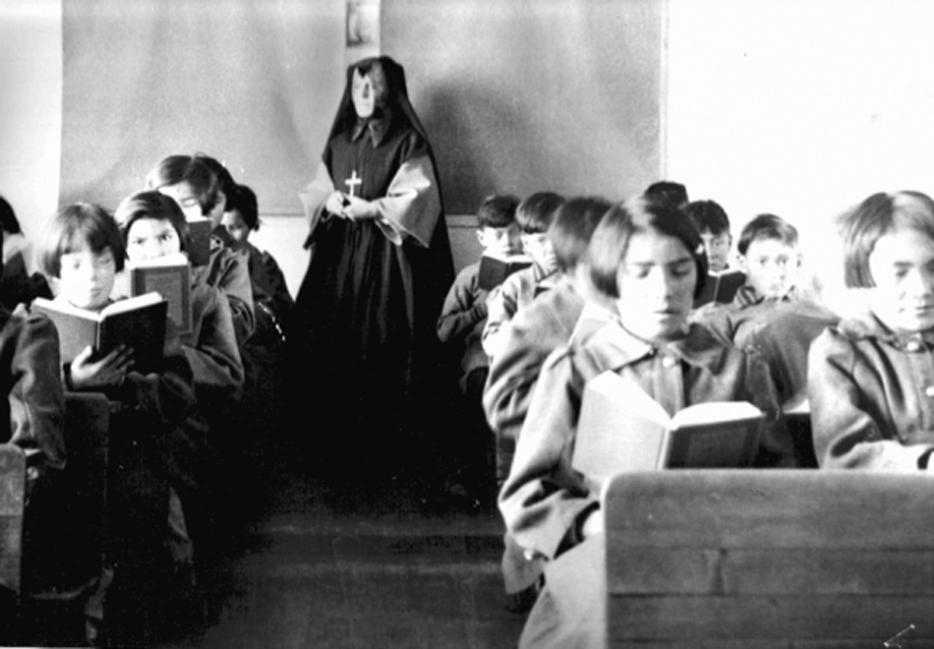

I asked Kristal the same question I’ve asked other cutters: why do it? Many adults say they started as kids in the residential schools—it was a coping mechanism in places where violence was the norm and kids weren’t allowed to complain—and continue now because it provides a release, a way to numb that internalized pain. The kids, in general, say they do it because they’re bored, but chalking it up to boredom seems like a deflection. Forced relocations, addictions, flooding, arson—this is life on a troubled reserve. Small wonder that they look for an escape.

*

Late last September, the Ottawa-based agency that had done the most to document the residential schools’ legacy, including the incidence of self-harm in survivors and their children, closed. The Aboriginal Healing Foundation (AHF) was a research body, publishing dozens of studieson the impact of the residential schools on individuals, families, and communities, much of which linked many of the problems that affect aboriginals today—poverty, discrimination, child abuse, self-harm, addictions, under-education and poor health—to the schools’ legacy.

Building on its research and analysis, the organization began to fund residential school healing programs in First Nations communities across the country. With its closure, 134 such projects are scrambling to stay open. “There are school survivors and their families who are stranded,” says Yvonne Rigsby-Jones, executive director of Tsow-tun Le Lum, which translates as “healing house” in Halkomelem, a Coast Salish language.

There have been several reports on the importance of long-term help for residential school survivors, arguing against the sort of dismantling of these programs we’re seeing now. Among the most notable was the 2012 Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s Interim Report, written by Justice Murray Sinclair. There was no quick fix, Murray found, to the legacy of residential schools—he described them as an act of genocide—and warned that abuse and self-harm were often passed down to the next generation. He gave several reasons: the schools normalized violence through physical beatings, whippings, and sexual abuse; they discouraged any natural attachment from developing between caregiver and child by banning expressions of love and affection; and, beyond the physical abuse, the schools fostered a violence of the mind by planting the seeds of self-hatred. Expressions of native identity—race, religion, clothes, customs, traditions, games, names, food, and language—were forbidden and demonized. These are the wounds, even self-inflicted, that can’t be hidden under sleeves.

The local high school is on permanent suicide watch, and has been since 2007, when 21 people, mostly children, attempted to kill themselves as part of a pact. Staffroom signs warn teachers of the types of things kids tend to say when they feel they can’t go on: “I wish I was never born”; “I won’t need this anymore”; “My parents won’t have to worry about me anymore”; “Everyone would be better off if I was dead.”

In Kashechewan, the effects of the residential schools are hard to avoid. You see them in the eight-year-olds who scan the dirt roads looking for cigarette butts to smoke. You see them in Kristal, asking me if I want to accompany her to an empty house to watch porn. You see them in the frequency with which drunken men come to my door after monthly welfare, asking if I want to come and hang out—but where? There are no restaurants on the reserve, no bars, cafes, gyms, swimming pools, concert halls, or movie theatres—nowhere to chill but the forest or the garbage dump.

And you see them in the suicide rates. Although there are no official statistics, the local fly-in coroner estimates that 2.5 people take their lives per year in Kashechewan, which would put the town at 11 times the national average—and at epidemic levels. (A suicide epidemic does not have an official statistical definition, though the United States is said to be in the midst of one, its rate having jumped 30 percent in the past decade, up to 17.6 deaths per 100,000. This rate is eight times lower than in Kashechewan.)

When I talk to the Kashechewan high school students, many tell me they have taken significant time out of school to recover from the suicide of a family member or close friend. The local high school is on permanent suicide watch, and has been since 2007, when 21 people, mostly children, attempted to kill themselves as part of a pact. Staffroom signs warn teachers of the types of things kids tend to say when they feel they can’t go on: “I wish I was never born”; “I won’t need this anymore”; “My parents won’t have to worry about me anymore”; “Everyone would be better off if I was dead.”

It’s difficult to visit one of these troubled communities, to see the effects of the residential schools, and not agree with Mr. Sinclair’s plea for long-term help. The legacy of residential schools is part of the fabric of daily life, hanging deadly in the air, and healing from the decades of abuse inflicted by nuns, priests, and other staff can’t happen overnight. But of course, the very reason these institutions and healing programs are now being closed is embedded in the history of the residential schools themselves.

*

In 1995, Mi’kmaq activist Nora Bernard, herself a former residential school student, filed what would become the largest lawsuit in Canadian history, representing 79,000 other survivors. After years in the courts, the Canadian government settled the lawsuit with the creation of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement (IRSSA), and as of September 2007 began to implement it. Part of the agreement, the Common Experience Payment (CEP), provided financial compensation to everyone who had been at a residential school. Those who suffered extreme abuse were eligible for additional compensation through the Independent Assessment Process (IAP).

The government also established the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), based on the South African body of the same name. As with the South African version, the Canadian TRC’s approach to healing was two-fold. First, a series of hearings across the country, where survivors could come forward in a safe space to talk about what had happened to them—or, in the case of student-on-student abuse, what they had personally done. Second, funding was allocated to First Nation healing programs and institutions working with survivors. To this end, the Canadian government funneled $125 million to the Aboriginal Healing Foundation in 2007.

Before the TRC, the method of redress for victims of residential schools was cumbersome, lengthy, and upsetting. Victims would have to gather all their documents in order to first try to prove they were in the school in question (many residential school documents have been lost or were deliberately destroyed), then try to find proof they had been either been sexually or physically abused (from places that often did not keep medical records), find a lawyer willing to take on the case (usually pro-bono), and finally go about trying to build a case against the perpetrators of a decades-old crime, some of the witnesses of which might be dead, and the memories of which are often befuddled by trauma and sometimes alcohol. If, somehow, the survivor managed to achieve all this, he or she would then be entitled to a financial payout of perhaps a few thousand dollars. In 2004, Flora Merrick, then 87, of the Long Plain First Nation, applied for financial compensation for being beaten and locked for two weeks in “a small, dark room” when she was 15 years old, as punishment for crying too much after her mother died. The government spent $20,000 to challenge her $1,500 settlement on the grounds that such treatment was consistent with the “acceptable standards of the day.”

For those who won their claims, the victory was a mixed blessing. Some recipients who had suffered intense sexual and physical abuse developed unhealthy coping mechanisms in response—drug use, alcoholism, and self harm. It wasn’t long before the media began to report on the rise of extravagant behaviour and drunken accidents among those who were victorious in the courts. “Victims blow compensation money: Future no brighter for most who collected settlements” read the headline of a December 28, 1998 article in the Owen Sound Sun Times, in which journalist Janice Tibbetts visited the Gordon reserve near Punnichy, Saskatchewan, to see how a recent settlement had affected the community. “Stories abound on the reserve of 1,200 about how people squandered their money,” she wrote. “While just about everybody bought a vehicle, there was one man who bought seven, one for every day of the week. And there’s the group that traveled 100 kilometres south to Regina the day they collected their money, rented the top floor of a swanky hotel and partied the night away.” A 2007 study published on the Aboriginal Healing Foundation website quoted one residential survivor who observed, “If you don’t start healing, the money will kill you.”

To help former students to better cope, the AHF developed a healing model that would later be exported across the country. Critically, any healing project funded by the AHF would be run by the First Nation community itself, and led by a “wisdom circle”—a group of local elders and leaders that have agreed to make a years-long commitment to manage the projects according to the community’s needs.

“Trust is the very first thing that we build,” explains Travis Enright, a Cree healer and Canon Missioner for Indigenous Ministry in the Chair of St. John de Brébeuf at All Saints' Anglican Cathedral in Edmonton, who has worked on several AHF projects. “It takes time, and is a matter of developing relationships and unlearning what is often a lifetime of learned distrust.”

The healing programs were designed to last at least ten years; the sustained engagement was to counter-act the short-termism that’s been a hallmark of troubled reserves. Historically, trained professionals have moved to these communities with high hopes, only to leave after just a few months, burned out by the difficulties of dealing with daily trauma, combined with the lack of access to drinkable water, affordable fruit and vegetables, a fire department, public or green space, and quality housing. To curb the trend, each community had to demonstrate it had a game plan for how to heal the healers.

The methods varied from community to community, dependent on whether the residential school survivors were comfortable with western scientific practices, Christian, indigenous, or all three. But for many in these communities, the Aboriginal Healing Foundation programs provided their first access to native healers.

Sharing a race and culture with a healer is critically important, explains Edmund Metatawabin, 66, a former Cree First Nations Chief, who detailed his residential school experience in Up Ghost River: A Chief's Journey Through the Turbulent Waters of Native History, a book I co-authored. Metatawabin is an advocate for the survivors of St. Anne’s Residential School, Fort Albany Ontario, which is notorious for the cruel and unusual punishments it inflicted on students. Metatawabin was sexually, emotionally, and physically abused at his school—even electrocuted in a homemade electric chair. Afterwards, he had difficulty with intimate relationships, and flashbacks during stressful situations. The P.T.S.D. from his childhood drove him to alcoholism. He tried various western therapies, with little to no success. It wasn’t until he attended Cree ceremonies performed by elders in Edmonton, at the age of 31, that he was finally able to let go of the pain he’d buried since childhood. “The ceremonies taught me how to accept myself and live according to traditional values. It was about unlearning the learned self-hatred. I had to discover how to take back what was stolen from me in my residential school.”

On June 11, 2008, Stephen Harper formally apologized for the government’s role in the residential school system, and acknowledged that the chronic social and psychological problems facing many First Nations communities were a direct result of the schools, and that healing would require a long-term commitment. Two years after those historic words, Harper’s government announced that funding for organizations like the Aboriginal Healing Foundation would run out by 2014.

The differences between indigenous and western healing are as profound as traditional Chinese and Ayurvedic. At root, the contrast stems from the nature of personhood, and what it means to be well. In native cultures, illness is said to arise when elements of a person are out of balance, be they mind-body, individual-community, or person-environment; all are interrelated, and together form the cosmos of health. Treatment is a matter of learning how to be a good person according to indigenous values—“Walking the Red Road”—and engaging in spiritual ceremonies that synchronize these different components of self into a functioning whole.

The distinction leads to the promotion and acceptance of different kinds of treatments. In the west, for example, cutting is considered a poor coping strategy. In order to heal, patients must figure out how to control the urges toward self-harm and replace them with more productive behaviours. But cutting is not in itself a negative act in Cree culture, as Enright says—rather, it’s a manifestation of a troubled soul releasing “a bad spirit.”

“Cutting is simply the symptom,” he explains. “Every healing ceremony we do is a matter of filling the soul with something good and positive. It’s about reaching this synergy. Once equilibrium has been reached, the cutting will reduce by itself.”

*

For a brief while, it looked like communities like Kashechewan would get the help they deserved. On June 11, 2008, Prime Minister Stephen Harper formally apologized for the government’s role in the residential school system, and acknowledged that the chronic social and psychological problems facing many First Nations communities were a direct result of the schools, and that healing would require a long-term commitment. “[T]he government now recognizes that the consequences of the Indian Residential Schools policy were profoundly negative,” said Harper, “and that this policy has had a lasting and damaging impact on Aboriginal culture, heritage and language.” He promised that the government would move “towards healing, reconciliation and resolution,” and take “a positive step in forging a new relationship between Aboriginal peoples and other Canadians.”

Two years after those historic words, Harper’s government announced that funding for organizations like the Aboriginal Healing Foundation would run out by 2014, likely meaning their closure.

“[The TRC process] opened up a Pandora’s box,” says Ms. Cynthia Wesley-Esquimaux, the Vice-Provost of Aboriginal Initiatives at Lakehead University in Thunder Bay, who has published studies on the legacy of the residential schools. “You got people talking about the things that happened to them that were very hurtful and painful, but now you have no process to deal with those feelings. You’ve shut down the process that would have addressed it.”

In international circles, the short-termism of the Canadian story is unique. Several countries have addressed historic crimes through their own Truth and Reconciliation Commissions, including Chile, Argentina, and the aforementioned South Africa. In the beginning, there were procedural similarities: each nation organized public hearings where victims and their families could tell their stories in order to compile official documentation of what happened. Financial compensation was provided for victims. Some countries have offered amnesty to participants who may have perpetrated crimes (South Africa), while others have not (Canada and Chile).

Any similarities with the Canadian situation end there. Elsewhere, reconciliation is treated merely as the beginning of a longer process, one that might take a generation or more. In 1991, Chile’s National Commission for Truth and Reconciliation issued its report on the deaths and disappearances that occurred under General Augusto Pinochet. Dozens of people were convicted, and yearly reparations to the victims continue to this day. To avoid repeating the mistakes of the past, civilian institutions were strengthened and new rights laws were passed; judicial independence was protected. The country created an Institute for Human Rights with an ombudsman’s office.

The process was similar in South Africa. When that nation’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission issued its final report in 1998, it acknowledged that testimonies were not enough. In its wake, the Cape Town-based Institute for Justice and Reconciliation was founded to continue the process, working to address the long-standing inequities fostered by the apartheid system. Rebuilding the country after a period of prolonged trauma would mean building a more just society and empowering those who were victimized.

To ensure that the Canadian residential school victims would not be abandoned, the AHF aimed to become a permanent fixture on the non-profit scene, lobbying the government for the funding to stay open. Even with the $125 million it received in 2007, it was hard to access every community requiring help, explains Wayne Spear, former AHF communications director, who wrote a book about the issue: Full Circle: The Aboriginal Healing Foundation and the Unfinished Work of Hope, Healing and Reconciliation, published on the AHF website. “Canada is a big country,” Mr. Spear says. “There are 633 First Nations. There are still people who say, ‘I’m ready now to get treatment, counseling, and address the trauma.’ But it’s too late, because we are closed.”

While the AHF was the largest organization of its kind, it’s not the only one shutting its doors. Recent government cuts have closed several other groups helping survivors and their families, including the National Aboriginal Health Organization and the National Residential School Survival Society. “There’s a sense by the government that we apologized and now it’s time to move on,” explains Mr. Spear. “To this end, anything to do with residential schools, they cut.”

It all sounds very familiar. Abuse in the residential schools continued because children could not tell anyone when it happened. It persisted because Aboriginal parents were ignored when they pressured the government to look into stories of staff sexually and physically violating their kids. That abuse contributed to the high death rates of children whose health was entrusted to the state: in some schools, as many as one in two students died, according to John Milloy’s A National Crime: The Canadian Government and the Residential School System. And today, the institutions that gave a voice to the survivors and their families, such as the Aboriginal Healing Foundation, National Aboriginal Health Organization and the National Residential School Survival Society, are dead or dying. The mechanisms designed to address the legacy of the schools are disappearing, although its many wounds remain.