One late spring evening in 2018, Justo Gallego Martínez said he would show me his grave.

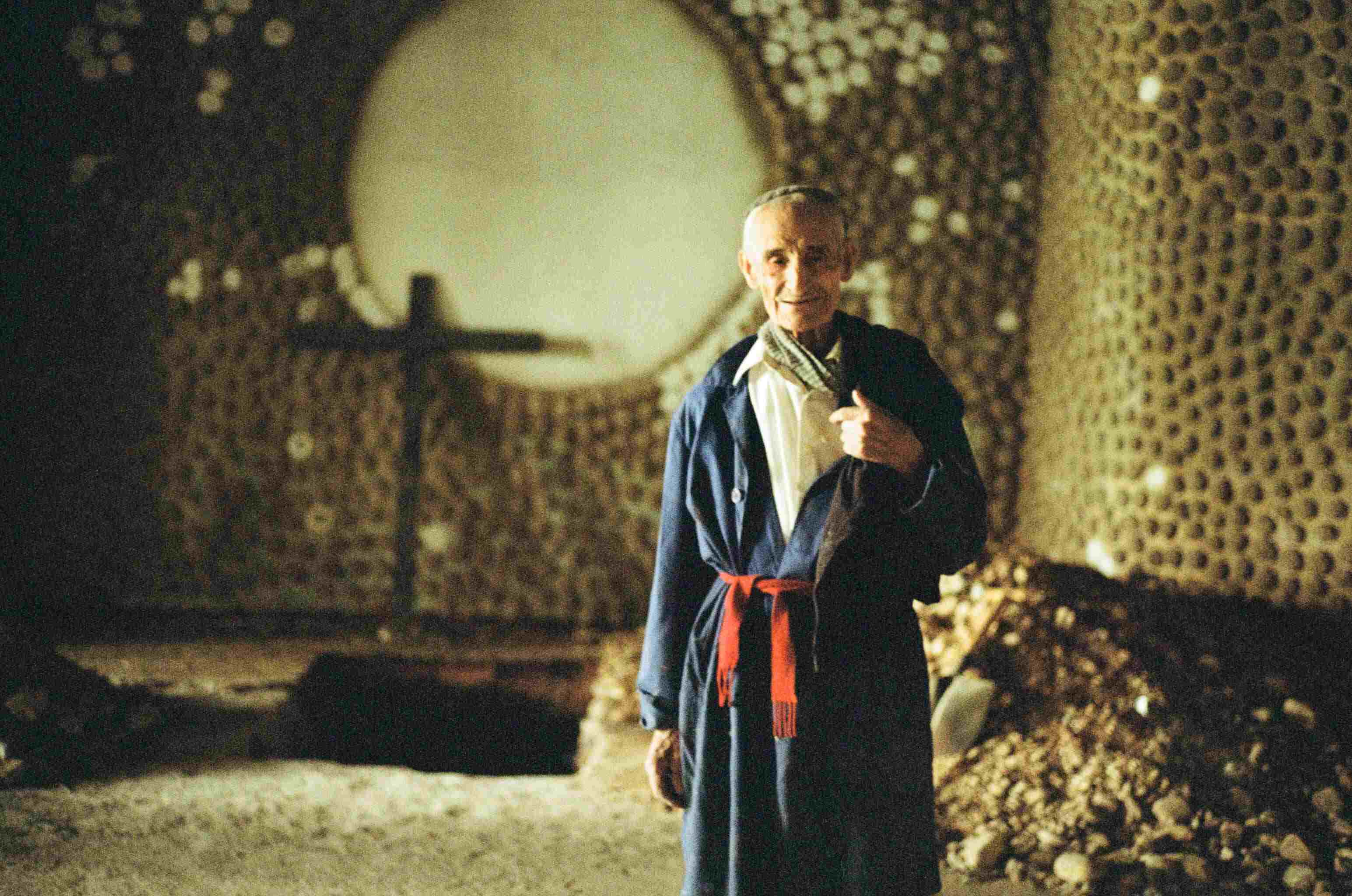

The old man was warming his hands by a stove in the dim back room of his cathedral. A dusty film coated the cement floor. The shelves and tables were full of relics, screws, chipped wood, crushed glass, and half-eaten loaves of bread. A bare hanging bulb cast the room in a jaundiced light.

“I want to be buried here,” Justo said, signalling around him to the cathedral’s cavernous nave and the twenty trembling towers sprawled across thousands of square feet of his own land on the outskirts of Madrid. He wanted to die where he had spent all his life hiding from a world that had never quite understood him.

The cathedral’s crypt would be his burial place. And he’d be buried there because it was his cathedral. He’d designed it entirely in his head, without a single measurement or calculation on paper, without a record of any of the materials he’d used. And he had done it largely by himself.

I sat near Justo in the gloom and watched as the fire threw shadows across his sunken eyes and recessed temples, as it flickered over his gummy smile, his gnarled hands, and his frail, angular body. He was nearly a century old, but energy still pulsed through him.

“Come on, let me show you,” he squawked.

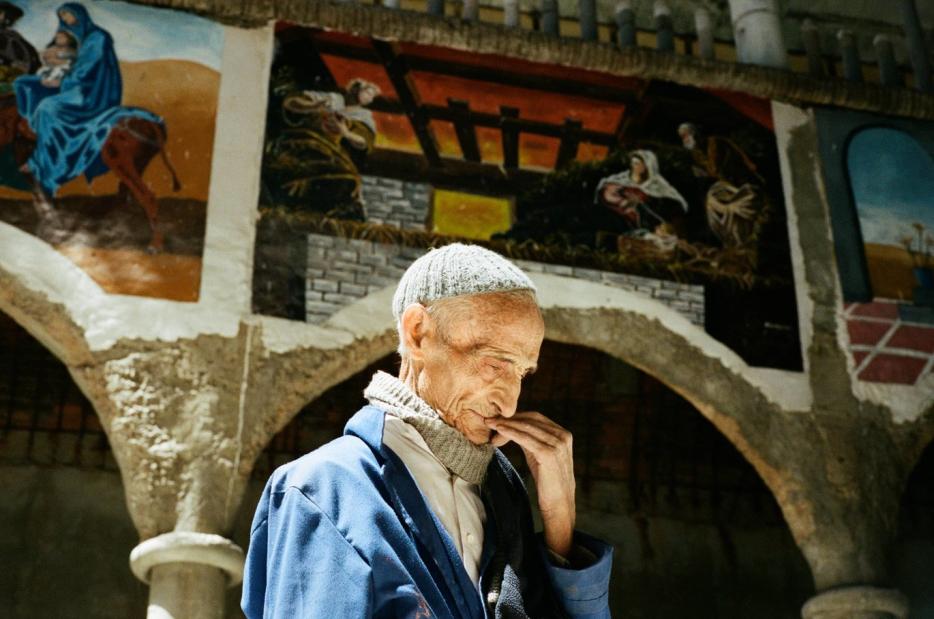

Grabbing my arm, Justo winched himself up from his seat and led me out the door to the ambulatory. His baggy blue coat hung from his skeletal frame like wet clothes on a washing line, and his hunched old shoulders and limp hands made him seem grim reaper-like in the darkness.

Outside, an uncovered dome, 120 feet high and 30 feet wide, loomed above us. The nave lurched some 150 feet to our left, covered by a half-barrel vault whose exposed beams curved upwards like a whale’s ribcage.

The rest of the cathedral was an architectural Frankenstein propped up on mismatched bricks, tires, wheels, food cans, plastic, and excessive quantities of cement. Large chunks of the building were already in decay, invaded by moss and rising damp. The aisles burst with dusty cement bags piled as high as the first-floor gallery. Other rooms erupted with thousands of broken tiles, dismantled cement mixers, motorbikes, rotten wood, oxidized saws, festering ropes, chicken carcasses, and plastic bags fossilized in pigeon shit.

Justo didn’t look up or down. He shuffled over the slippery marble tiles to the altar at the back of the apse, passing by a life-sized crucifix cast in white plaster.

“Down there,” he pointed.

Next to the shrine, the floor opened like a sinkhole to the darkness of the crypt below. This hole was where it had all begun, Justo said. Here, he had first started to dig and to formulate his vision. Here, too, at the back of the crypt, in the half-light of the lower courtyard, is where it would end.

A six-foot-high wooden cross leant against the wall. In front of it lay a yawning pit, seven feet long and four feet wide, a pyramid of dirt heaped at its side. The bottom was too dark to see. But Justo wouldn’t look at it. He just stared out at the courtyard, at the crumbling cloisters and the glinting dooms, at the sprawl of his cathedral.

***

I had lived in Spain for almost six years before I heard about Justo. In early 2018, I came across an article in a local paper about an ex-monk building a cathedral in Mejorada del Campo, a town on Madrid’s outskirts. For almost sixty years, with no help or architectural expertise, Justo Gallego Martínez had been constructing a cathedral near the size of the Sagrada Familia using waste and recycled materials.

When the monk started his project, the locals had called him a madman. Since then, he had fought with family members, created enemies, and won an adoring international public. He had also never formalized the structure, which means that his cathedral was illegal. The Official College of Architects of Madrid confirmed that “not even the preliminary papers [for registration] have been submitted.”

Representatives from the Catholic Church would later tell me that it is too expensive and complicated a project to take on. And the provincial government maintained it didn’t have the money to renovate it to standard. There was a real worry among the locals that the cathedral might be torn down.

Several months after reading about Justo for the first time, I found myself standing next to this bewildering man, as he stood next to his own grave.

On paper, there was little to unite the two of us. I was a twenty-seven-year-old agnostic baptized in a Presbyterian church, a writer who had always been rather obsessed with the meaning of his own work, which is a sententious way of saying I was harmfully ambitious. My desire to succeed, or whatever I thought that meant, kept me up at night, made me irritable and anxious, imbued me with a sense of superiority on some days, and crippled me with self-loathing on others. Justo, on the other hand, was an extremist Catholic. He had deferred the meaning of his creation to God and was seemingly obsessed, not with his ego (which was an anathema to him), but the purity of his devotion.

While, during those early visits, I might have been tempted to see Justo’s dedication as some sort of existential mirror for my own roaming, distracted mind, as I got to know him better, I realized that, like his cathedral, everything was more complicated than I had perhaps wanted it to be. In reality, Justo was a mess of incongruities and non sequiturs. He could be open-minded and bigoted, forgiving and stubborn, kind and brusque, wise and simple. He was a flawed genius, who never sought to be named as such, a man who didn’t want to be discovered, but had done everything to make himself discoverable. His achievements had attracted people from all over the world, but his inability, or perhaps just an unwillingness, to articulate his own vision had allowed those people, including me, to write his story for him.

***

Justo’s early life was marked by religious fervour, political upheavals, and health problems. As a boy, he was very close to his mother. “She was a saint,” he told me. “She was the one that taught me the words of the bible.” At an early age, he had to leave school due to the Spanish Civil War, which ravaged Madrid and its surroundings. His mother’s teachings were a vital part of the little education that Justo would receive.

The young man had always fostered dreams of dedicating his life to God. When he would travel to Madrid to run errands, he would roam the capital’s streets searching for a woman more beautiful than the Virgin Mary. “But I couldn’t find her,” he sniggered. So, the boy chose to consecrate his life to the Virgin and remain a virgin himself—a man of God, not tempted by the flesh or carnal desires. “I want to be pure, not a slave to my body.”

At the age of twenty-seven, he entered the monastery of Santa María de la Huerta in Soria, northern Spain. Many of his fellow monks found him strident and difficult; he would work longer hours than necessary and often pray into the night. Insisting on remaining teetotal, he even refused to drink the wine during communion. “They were very suspicious of me,” he once told local journalists. “They said I was breaking the rules.”

Seven years after he first entered the monastery, Justo said he contracted tuberculosis. He travelled to Madrid to recuperate in the hospital that now houses the Queen Sofia National Museum Art Centre; how long he spent there is unclear, though he claimed it was a year. When he tried returning to the monastery, his brother monks did not allow him back in. I once asked Justo whether he thought this had to do with his extremism or his illness, but he was reticent on the details.

Justo merely said that he returned to Mejorada del Campo and fell into a funk, a sort of depression. He no longer knew how to dedicate his life to God. “The brother monks have abandoned you,” his mother would tell him, and Justo indulged in her pity. He began to live like a hermit. He spoke to no one, not even his friends; he thought only of God and the Virgin Mary, in whom he sought solace and inspiration.

Where would he channel his religious fervour? What could he possibly do with himself that would mean anything? It was in the midst of this incessant self-questioning, he said, that it came to him—the idea to build something for his Creator: a cathedral, which would demonstrate his willingness to sacrifice himself for God.

In 1961, Justo started to dig, laying the foundations of what would become his life’s work. He came from a relatively well-off family with considerable land near Madrid. Over the years, he sold much of it to fund the construction of his church. He also relied heavily on charity; a factory in a nearby village supplied cement, while another offered broken tiles and discarded bricks.

Working alone, he barrelled mountains of dirt, scaled scaffolding with no harness, and soldered with no mask. He worked feverishly, without rest and with little food and water. Sometimes he would have visions. Laying bricks, he would suddenly remember the Holy Trinity, drop to his knees and weep. “I don’t know if these visions were mystical,” Francisco Martinez, a local priest, told me, “but he definitely had many intense, visual experiences with God.”

Justo hated angles and straight lines and tried to avoid them in his cathedral at all costs. He preferred curves and circles—vaulted ceilings, domes, arches, rounded chapels, annular altars, and spiral staircases. “God made all things round. He made the planets round. He made the earth round.”

While God may have spurred Justo on, his lack of education held him back. He read little beyond religious texts and had no grasp of even elementary mathematics. He didn’t know about circumferences, radii, or diameters. So he found his own way to make circles: he’d bend metal rods around columns, draw around circular water drums or tins of paint. But Justo knew making curves was no easy task. They were expensive, had little tolerance for error, and were harder to build than straight lines. Everything had to be calculated to fit within centimetres of accuracy. A millimetre of imprecision in one step could culminate in a spiral staircase that didn’t quite reach its landing.

The curve Justo loved most was the dome. Measuring 120 feet high and 30 feet across, it was modelled on the St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. Still, unlike its more famous inspiration, Justo’s dome was a quarter of the size and unfinished. With large blue metal girders curving up to a pressure ring at its centre, it looked like a mechanical spider atop the nave. The dome took him thirty years to imagine, and seven years to build.

It is what he talked about the most and the only thing I ever heard him boast about. “You won’t find anything like this in Madrid,” he’d say. There were never any plans or drawings for the dome. Though he received help from ironworkers, Justo implied that he did the work alone.

When I queried how that was possible, the answer was a mishmash of incomprehensible anecdotes. There were stories of spindly scaffolding 250 metres high, no harnesses, groaning metal bars, and strong winds. “I was always worried about the wind,” he told me. But when I pressed him further, when I asked him how he had actually built it, Justo merely said he had managed it through a combination of determination and prayer. There was no reflection or consultation unless it was with God.

Nor was there much inspiration from architects, who Justo didn’t like being compared to. Besides religious texts, he only read books on medieval castles and gothic architecture. For him, Gaudi, the architect of the Sagrada Familia to whom he is often compared, was “garbage.” “His stuff is completely over the top! There are too many spires, too much of everything.”

Justo made up for his technical shortcomings by finding strange solutions to seemingly insurmountable problems. He piled empty paint cans on top of one another and filled them with cement to make columns. He bent corrugated iron rods and fed them through slinky-like springs to create the structure for arches. When the columns he built were too short, he filled the gaps with clumps of iron, piling them up like mismatched books to the height of the support beams. He’d then solder them together.

To Justo, building was more an instinct than an acquired skill. He reacted rather than pondered, and he mustered things he wasn’t able to process or explain later.

***

In the ’60s and ’70s, Spain was in the midst of a dictatorship predicated on deeply conservative Catholic values. This would have suited Justo, except that the dictatorship also brought with it an atmosphere of paranoia and suspicion. People kept their politics to themselves for fear of repercussions. The age was permeated by a pernicious silence and a regression to the refuge of the norm.

Over the decades, as the ex-monk continued to build, most of the villagers declared him an outcast. A madman. “He was the type of person dressed in a winter coat in the summer and summer clothing in the winter,” recalled Lucia Moncada, a local resident. He was the kind of man who didn’t fit in. To Justo, however, these types of criticisms had no effect. “It’s easy to overcome judgement,” he once told Spanish television. “They called me crazy. . . . So what?! I’ll get over it.”

But Justo wasn’t crazy. He was just unwilling to submit to what most people considered normal. He wasn’t accommodating of others’ concerns. He didn’t need love or approbation because he had purpose. That was enough. That was his strength. His marginalization, his self-removal from the world, allowed him to work, to achieve what most distracted minds never could.

And if Justo worked mostly alone on his cathedral, it is also partly because he had struggled to find anyone he consistently got on with. When he first started his project, he was helped by his nephews, and to compensate them, Justo built houses with the money he received from the sale of his lands. According to Justo, he also gave them access to funds to support themselves while they assisted with the construction. But the nephews soon began taking advantage of their uncle and drove him into debt. In the early ’80s, the bailiffs came knocking, and Justo said he had to move into the cathedral full time. He had no money to continue the construction and no hope of sustaining his commitment to God. “The biggest devils I have ever come across are in my own family,” he said of his nephews.

That’s when Ángel López appeared. He started visiting Justo in the early ’90s. After living and working alongside the old man, Lopez—a squat, beefy labourer from Guadalajara—told me he had an epiphany and renounced his former life to move into the cathedral with Justo. He sold his apartment in Guadalajara and paid a large chunk of Justo’s debt.

During the three years I spent in and around the cathedral, I found Ángel hard to place. Sometimes, he would speak to me like I was his accomplice, whispering to me his confidences in chummy conspiratorial tones; at other times, he treated me as if I were an incompetent foreigner who barely understood Spanish. Often, he seemed to be doing his own thing. He would be out hunting rabbits or at the bank for longer than seemed likely. He was always going somewhere, always surprisingly unavailable. He was not filled with Justo’s religious fervour, nor did he have his charisma. Though he always spoke fondly of Justo, calling him his “master” and a “genius,” he could also be spectacularly unenthusiastic about the cathedral’s future. “When Justo’s gone, there is no plan,” he said when I asked him about it.

There was suspicion surrounding Ángel. One local believed that he was as bad as the nephews: “Ángel has Justo wrapped around his little finger. He is playing the long game, waiting for Justo to die so he can cash in.” But Ángel remained incredulous in the face of these rumours: “I paid Justo’s debts. I have been here for years and still they think I’m bad.”

As Justo got older and sicker, Ángel’s influence had become more palpable. Though he was undoubtedly loyal, I often sensed that Justo had become his mouthpiece, wheeled in front of the public when it suited him to say what he himself couldn’t say. Ángel had been in the cathedral for twenty-four years and it brought him a sense of entitlement.

Whether his intentions were sincere was never easy to divine, but I often found it hard to reconcile his presence there. Why had Justo rejected the help of so many other people for so long but ended up with Ángel?

When they were together, the two men bickered like seagulls, squawking and squabbling their way into getting nothing done. “You’re getting worse,” Ángel would intone. “You don’t listen,” Justo would retort. In some ways, Ángel reflected Justo’s insecurity. Perhaps Justo feared that if he had taken on a more able helper, he would have lost control of his project. Perhaps Ángel’s ordinariness allowed Justo to stay in control longer.

But I also had to check my cynicism with reality. While I was there, I saw that Ángel religiously made Justo’s lunch and dinner. In the mornings, he got him out of bed and dressed him. He would take him to the doctors and to mass every Sunday. “He cleans my poo, he feeds me and he carries me in his arms,” Justo confided in me.

***

Throughout the late ’90s and early 2000s, Justo’s feverish devotion—“his craziness”—emerged as something more than just eccentricity. The cathedral was becoming more significant than any of the locals could have imagined, and Justo passed from madman to genius.

Soon, there was interest from local papers. Then, the national press came, followed by journalists from abroad. At the end of 2003, photographs of Justo’s cathedral appeared in an exhibition called “El real viaje Real / The Real Royal Trip” at MoMA in New York. However, Justo declined the invitation to travel to the United States because he had “too much work to do.” The cathedral became famous in 2005 when it appeared in an advertisement for the Coca-Cola brand’s Aquarius drink. “The advert became one of the most successful campaigns in Spanish marketing history,” Felix Muñoz, an executive working for Coca-Cola who commissioned the campaign, later told me.

It might seem ironic that a man uninterested in himself and his legacy would agree to let a company like Aquarius in. But Justo only acquiesced to the commercial so that he could get funds to continue his construction. He didn’t see the cash, only more bricks. Indeed, when the commercial was shot, Justo had no idea of the consequences or repercussions of his decision. He seemed confused, in fact: “I didn’t know it was going to be on TV. I thought they were just going to print something on the side of the can.”

The concept behind the commercial was the unpredictability and spontaneity of the ordinary man. “Heroes didn’t need tight latex and red capes,” Muñoz told me; they could be common men and women who came from nowhere and asked for nothing. In Justo, Aquarius found extraordinary ordinariness. “He wasn’t your typical handsome young actor,” Miguel Garcia Vizcaino, the commercial’s director, recalled.

During my first trip to the cathedral, I, too, bought into the commercial’s branding of Justo. I had always been haunted by the ideal version of myself that I wanted to be. And in Justo, I found a decisiveness that censored my relentless self-doubt, muffled the self-questioning. Justo repeated the same routine every day, until one day, he ended up with something not even he could have imagined.

But, like the commercial, I had misinterpreted Justo. He did have an unshakeable belief, that much was true. But it wasn’t in his own self-refinement; it was purely in God. If he hoped to inspire other people at all, it was by encouraging them to follow his lead and become closer to God. “What I have done with the cathedral is an apostleship,” he told me on many occasions.

I would later come to see the cathedral as a carapace that protected Justo from temptation and vice, from the everyday of the outside world. The irony was, of course, that this fortress for his ego was so impressive that the world came to hear of it, to see it, and to venerate him for it. While Justo had tried to embody temperance and humility, one of the world’s largest brands had turned his abnegation of the ego into the exact opposite—a celebration of individual accomplishment. Aquarius had made his faith synonymous with ambition, his devotion with perseverance, and his sacrifice with self-interest.

Over the years, tens of thousands of people have come to visit the cathedral. They all want to see Justo. To touch him. To hear him speak. To understand him, his inspiration, his genius, and his imagination. I saw old ladies kiss him, fervent pilgrims grab him, and people approach him with schemes to protect and reform the cathedral. People often talked about him in saintly terms. They marvelled that, during almost sixty years of construction, he had suffered no significant injury. Carlos Luis Martin, an architect who helped Justo at the cathedral, recounted witnessing an accident: “I was working in the crypt. Justo tripped over a stone and fell and smashed his head on the ground hard. . . . But [he] just got up. ‘God has healed me, and now all is fine,’ he said. And there was not a scratch on him.”

Still, Justo often found all the attention difficult. He would get angry and clash with visitors. He would call them “idiots” and make them delete their photos. He would berate women who came in wearing short skirts. He put up signs saying he was not to be spoken to. Carlos Silvera, a Madrid-based artist who painted the cathedral’s murals, remembered when a young woman visited the cathedral and told Justo how impressed she was with him. “She said she had studied art. She told him how she had travelled. She told him how she understood religion. But as she was talking, Justo interrupted her: ‘You use the word I a lot, don’t you?’ The young woman went quiet and began to blush. ‘You know that your biggest enemy is I.’”

Justo always had it within him to be tactless and unsympathetic. He could not see, or perhaps refused to see, what his building meant to others. He wanted to keep its significance tied to God, and failed to understand how it moved and inspired those who came to see it. Indeed, as the cathedral’s wobbly towers began to rise above the drab uniformity of Mejorada del Campo, capturing the world’s attention, Justo wasn’t able to fathom why he could no longer control his story. He even became resentful. When Felix Muñoz returned to the cathedral two years ago to visit Justo—having not seen him since the shoot in 2005—he found a man and an attitude he was not expecting. Justo told him that the advertisement had only brought him problems. “He told me he wished it hadn’t happened.”

I bore witness to Justo’s frustrations on several occasions, no more so than one afternoon in late 2018, during my second weeklong visit to the cathedral. My friend Denis Dobrovoda, a Slovak film director, had turned up with a camera. Both of us had wanted to make a film about Justo and his work and had struck the same deal with him as at the beginning of the year: we would work, and he would let us film. However, when he saw the camera and drone—the “machine” and the “little plane,” as he called them—he decided we had been dishonest with him. He had assumed we’d bring a small “machine,” not a “giant one.”

In what felt like a punishment, Denis and I were sent down to the lower cloisters to clean up the mess that had accumulated there over the years. We rifled through plastic bags, rotten insulation boards, and chipped marble and granite. Justo loitered in the courtyard, mumbling to himself. Suddenly, his gaze focused on an abandoned fish tank made of thick glass, congealed glue protruding from its joints. In the middle of the tank was an amorphous tower of dried clay. It was hard to figure out precisely what it was—perhaps an abstract rendering of the cathedral or maybe merely a lump of sand. To Justo, however, it was now a “monstrous vanity” gifted to him by “some rich person.” “It has to be destroyed!” he snapped.

Justo barked at us to ram a heavy wooden plank that was lying nearby against the side of the tank to break the main structure. It was typical of him to use whatever was immediately available to solve a problem.

Justo was frail, his skin thinner than rice paper, and neither of us wanted him to cut himself on the glass. We were also aware that he was allowing us to film him in return for our work. So, rather reluctantly, we bashed the plank against the fish tank, hoping that nothing would happen.

The dull thud of hardwood hitting the thick glass confirmed our expectations. It wasn’t working, so I suggested we stop. Justo, however, was insistent: “Find me an axe! We need to destroy this—now.” The more we tried to convince Justo that this wasn’t a good idea, the more aggressive he became. We would be kicked out of the cathedral! We were devils!

My first thought was to find Ángel, the only person who could talk Justo down. Ángel was nowhere to be found; an axe was.

I was indecisive. Perhaps it would placate him, I thought. We would watch over him, and everything would be fine. After all, he’d been doing things like this for sixty years, and he’d never been seriously injured. So I handed Justo the axe. He snatched it from me and began bashing the glass of the fish tank. The first layer shattered, bursting like an old-fashioned camera bulb. Justo scrunched up his eyes and pursed his lips. He raised the trembling axe again. And again.

Justo’s jacket sleeve slipped down his arm, and I saw that his veins ran like roadmaps down his arms. I saw the thick, sharp glass. I watched his rickety wrist, his eyes scrunched up like crumpled paper, the splinters of glass spurting up like hot steam with every swipe. I imagined the glass slicing through his skin, the blood gushing from his arms. I pictured Justo on the cathedral floor, dazed and white as marble. I imagined the ambulance arriving, and heard our feeble explanations. I had imagined enough.

I ran up to him and snatched the axe from his hands. Justo balked, “You scoundrels! I’ll kick you out if you ever do that again. This is my cathedral.”

***

By the end of 2019, Justo’s health began to deteriorate, and his undiagnosed dementia progressed more quickly. He laughed less and made less sense when he talked. He also seemed increasingly frustrated. Ill and weak, he was frequently in and out of the hospital. Disorientation had become the defining factor of his life, and Justo was shrinking inside his cathedral, even as his reputation outside it continued to grow.

He spent most of his time sitting in an old office chair in his gloomy personal quarters. A puddle of murky, bloated lentils and a hollowed-out baguette often sat at his side. He was always cold: “I have no meat on me.” He stuffed scraps of cardboard, kindling, or anything that would burn into his rickety wood-burning stove. Occasionally, he rose from his chair, his bones creaking like warped wood. The scratchy shuffle of his scruffy black shoes on the cement floor presaged his arrival. Most of the time, Justo wandered aimlessly, taking things from here to there, picking up a piece of wood and inspecting it, dragging a pile of stones to nowhere in particular. He might then sit in another chair on the balcony that led to the cloisters, where he squinted at the sun, rosary beads twitching in his hands, muttering and murmuring to God.

Despite his deterioration, Justo still had his infectious, boyish enthusiasm that transcended generations and our respective beliefs. In fact, during those visits throughout 2019, I felt that our relationship evolved beyond its initial awkwardness. That summer, as we sat in the ambulatory together, he asked me about my family’s faith.

“Are your parents Christians?”

“Yes,” I told him. It was a half-truth; they were baptized agnostics like me.

“But have you studied the catechisms?” he asked again.

“No.”

“Well, I want you to have this,” he said, brandishing a book of catechisms. “It’s my gift to you.”

Another time, I remember being in Justo’s dingy backroom, stoking his wood-burning stove.

“You have to read The Imitation of Christ by Thomas à Kempis,” Justo told me excitedly. “It’s incredible!” (The book, one of the most important devotional Christian texts ever published, preaches that a good Christian should live an interior life by renouncing all that is vain and illusory. It was Justo’s second bible.) He retrieved a bashed-up copy from a nearby shelf littered with nuts, screws, and sandpaper, and handed it to me. “Read it aloud,” he ordered.

Without overthinking, I began to read: “How undisturbed a conscience we would have if we never went searching after ephemeral joys nor concern ourselves with affairs of the world.” Justo stood back, a contented smile on his pencil-thin lips, his eyes closed as if in prayer. The book seemed to be giving him sustenance and greater joy than, as à Kempis writes, a “multi-course banquet.”

But those moments were rare. Mostly, Justo just seemed lost in his cathedral and in his ailing head, which, he grumbled, “no longer worked.”

***

At the beginning of 2020, the cathedral was in a precarious situation. Justo was weak and rarely left his room. His impending death threatened to leave behind an administrative mess. The cathedral was illegal, after all—it didn’t exist on any register. And over the years it had swollen into a sprawling mass of iron and cement, with its gangly cloisters and crooked towers encroaching on the surrounding buildings. No architect was willing to sign off on its structural stability and soundness. The building did not meet any of the required standards. Anyone who vouched for its stability would be liable for any damages incurred by visitors. The local government was afraid that it might fall and so would not formalize it. The church couldn’t be consecrated if it didn’t have the correct administrative approval. It was a Catch-22, and neither the town hall nor the local diocese appeared willing to invest a cent in breaking it.

When I talked to the vicar in charge of all the diocese’s architectural projects, he was cagey about Justo’s cathedral. He said he wanted to set up a foundation to gather funds to save it. But, if the cathedral was saved, he couldn’t say “whether it would be used for religious purposes or not.” When I asked Ángel what he would do when Justo passed away, he looked at me blankly. “I don’t want to think about the day that Justo is no longer here.”

But locals and people farther afield still recognized the importance of the cathedral. YouTube is filled with young vloggers waxing lyrical about its importance. There are regular articles in Spanish national papers providing updates on the building’s legal situation. UNESCO representatives even paid a visit in early 2020. Still, these attempts to legalize the sprawling structure had been slow and bureaucratic. It looked likely that Justo would not live to see his cathedral saved.

Then, in May of 2021, Justo and Ángel donated the cathedral to an organization known as Mensajeros de la Paz, or “Messengers of Peace,” a Catholic NGO working in over fifty-five countries whose main goal is to help people living in poverty. Padre Ángel, the organization’s founder, had, like Justo, been deemed a visionary; a crazy man, he had started the organization by himself and had grown it into one of the biggest Catholic NGOs in the world.

Desperate for a solution, Justo and Ángel had asked the organization to take care of the church. Padre Ángel, who knew of Justo’s story, was enticed. He decided to take on the church—no matter how much it would cost, no matter how difficult an undertaking it might be. And he wanted to do it quickly. Within a matter of days, the donation had been notarized.

The organization swiftly moved into the cathedral, cleaning up the general mess, smoothing over cracks, reinforcing arches, putting up walls. They also sent in a company of the country’s best structural engineers, some of whom had worked with the most prestigious architects in the world.

During their initial surveys, the engineers were surprised to find that the cathedral was more structurally sound than had otherwise been thought. It was proportional and had been built in mind of the elements. “With so little knowledge of construction, it’s as if he’s invented architecture in his head,” one of them marvelled to me. Though the engineers couldn’t be sure that the cathedral was completely stable, they were surprised by how carefully it had been built. It was worth saving, of that they had little doubt.

But, at times, the organization’s involvement felt overbearing. Justo was disappearing from his own cathedral. He no longer came out of his room. He no longer shouted at volunteers. He was bound to a wheelchair or to his bed. As I walked around the cloisters, the nave, the crypt, his absence felt prescient; I sensed the cathedral’s future was out of his hands. It was being transformed in line with the Messengers’ own aesthetic. The nave was now decked out with their paraphernalia: huge posters depicting the pope hung on either side of the main altar, the Messenger’s maxims and motifs were written on the walls, and a makeshift food bank had been placed in the central nave. Justo’s name appeared on some of these new additions, but his presence felt largely posthumous.

The Messengers also announced they wanted it to be an open religious space where Muslims, Jews, Protestants, Orthodox, and Catholics could congregate and discuss religion. I knew Justo. I knew how antiquated and conservative he could be. I knew that he had fought for many years for his cathedral to be consecrated as a Catholic place of worship. I wondered if he’d be horrified at the Messengers’ vision.

***

The last time Denis and I saw Justo, he was on his deathbed, a colostomy bag hanging from his mattress, his bald head shining like a crystal orb. Ángel was by his side.

Neither of us had seen Justo for months, and we were hearing rumours of negativity and tension among Justo’s family and friends regarding the takeover. We wanted to know what Justo thought of the cathedral’s new guardians.

Propped up by a pillow on a hospital bed in his newly decorated bedroom, Justo’s voice was an octave higher than when I’d last seen him, his speech more accelerated, and his mind, as it always was, a swirl of thoughts and ideas. He was at times thankful, and other times angry, about what had happened. But more than anything, he just seemed confused.

I didn’t know what to take from this interaction. In truth, I felt Justo was too far gone to answer our questions, and it was hard to know what he was saying for himself and what was being said for him. When Justo’s words became muddled, Ángel often finished or interpreted his thoughts.

Over the following days, as I witnessed these meetings and saw how frail he had become, I felt sad that Justo had to be part of these discussions and tensions. After all, notions of legacy were in many ways anathema to him; legacy was vanity, and vanity was the devil.

I was taken back to that late spring evening at the end of my first visit to the cathedral, Justo standing precariously close to his grave. He seemed nonchalant, as if it were normal to pre-empt one’s death. “I’m ready for the end,” he mumbled, still staring out at the courtyard.

Justo told me he had been content with his efforts as far back as the late ’90s, even when the cathedral was half-finished and the central dome didn’t even exist. He said he’d tell those who asked him: “I’m already happy with it, I think I’ve done enough.”

Justo didn’t believe in perfection. How could he? Perfection was God. Unattainable. Perfection was really only the mask of ambition, and Justo wasn’t driven by ambition. His cathedral was full of half-baked ideas, trial and error and moments of brilliance. It was the inside of Justo’s head rendered in iron and cement.

“We are only in transit here on this earth,” he said, turning his head toward me. “In the end, it doesn’t really matter what we do here. It’s up there where it counts.”

For Justo, the cathedral was the sacrifices it entailed: the long labouring days, sleepless nights, solitude, and alienation. His sacrifices were his devotion to God, and while his legacy and reputation might be written by outside institutions like MoMA or Aquarius, by me, only God would know his real reasons. “What happens to the cathedral is now no longer up to me,” he said, glimpsing his grave. “I’ve done everything I need to do.”

Justo didn’t want to stand around any longer. He shuffled from the darkness of the crypt, through an arched doorway, out into the light of the lower courtyard, disappearing from view.

Justo died on November 28th, 2021.