My childhood fantasy went like this: Standing in a church doorway in a “Miss Pretty Princess” bridesmaid dress with a floral wreath in my hair, and bangs, which in retrospect have too much hairspray, I look up. “If You Were Here” shimmers in and a man who is criminally older than me appears, leaning against the door of a cherry red Porsche. Seeing him now, 25 years later, he looks a lot shorter than I remember, but back then, at age 10, I was a lot shorter, too. He’s still beautiful though, in a pair of perfect jeans, brown boots, a Fair Isle sweater vest as he coyly waves, as though any heterosexual woman on the planet, even one who isn’t one yet, would be happy to find him there. Just to be sure, I point at myself with my bouquet and mouth, “Me?” And he, his hair moussed up in front like the red fringe on top of a Roman helmet, whispers goofily, “Yeah, you.”

And that’s where it ends. There is no kiss over a cake because at 10 there were no kisses, just the dream come true: Sixteen Candles’s Samantha Baker finally landing her senior crush, Jake Ryan. “That’s like the perfect guy,” writer Jason Diamond says. “Except he makes rape jokes."

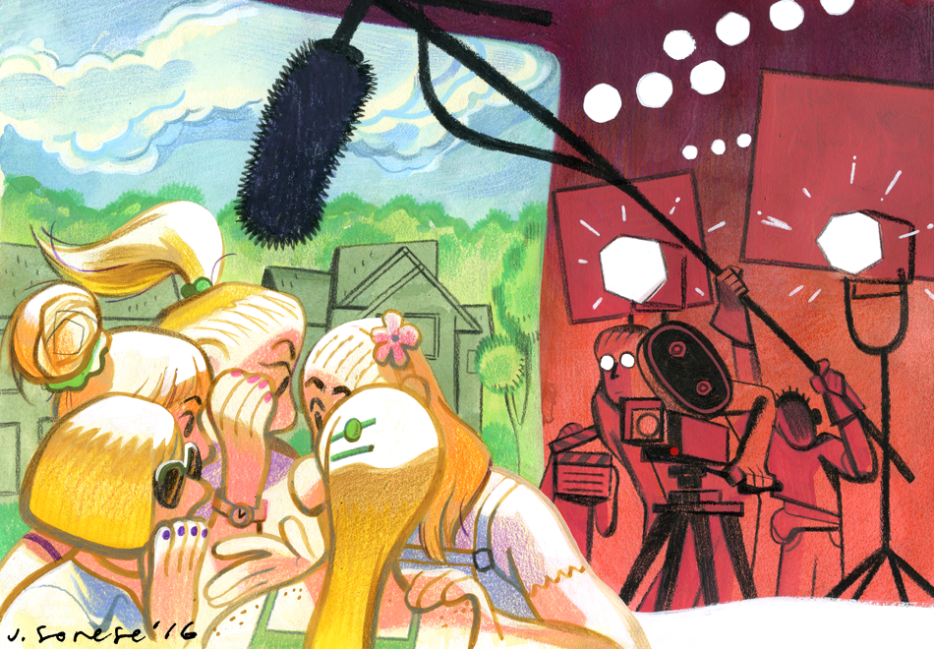

Diamond’s forthcoming memoir, Searching for John Hughes, details his life growing up in the northern suburbs of Chicago, Illinois, where John Hughes’s teen canon took place. For Diamond (who's also a Hazlitt contributor), and for me, Hughes’s films weren’t just aspirational fluff, they were aspiration leavened by reality. His heroes weren’t sun-smacked cover girls or matinee idols (well, besides Michael Shoeffling), they were kids like us—relatable role models. “They helped us figure out what to look for in our love lives, our friendships, our careers,” Susannah Gora wrote in You Couldn’t Ignore Me If You Tried; this applied particularly to the generation that grew up on them, particularly the girls. “It made girls of all makes and models feel like they could make a difference,” says Michelle Manning, producer on Sixteen Candles and The Breakfast Club. “It could not have happened if [Hughes] didn’t have Molly.”

Molly Ringwald, a pouty freckled redhead, was Hughes’s muse, starring in three of his four female-centric hormone-coms—Sixteen Candles, The Breakfast Club and Pretty in Pink. Hughes believed “girls tend to have a more considered view of life” and with the help of Ringwald, and other actresses such as Ally Sheedy and Mary Stuart Masterson, he created stronger, more complex female characters in an era that negated them. “He obviously loved women and saw his female characters as more than mere cyphers, there to make boys look good,” says Hadley Freeman, author of Life Moves Pretty Fast: The Lessons We Learned From Eighties Movies (And Why We Don't Learn Them From Movies Any More). They proved that feminism wasn’t dead even though America kept insisting that it was.11“By the mid-‘80s, as resistance to women’s rights acquired political and social acceptability, it passed into the popular culture,” wrote Susan Faludi in Backlash. Her 1991 treatise exposed the previous decade’s attempt to pave over feminism’s advances by accusing the movement of reducing so many women to Glenn Close circa Fatal Attraction.

John Hughes may have loved women, but the happy endings he gave them reflected the limitations of his own conservatism and that of the time. “As the 1980s body politic sought to rein in the female body that had been unleashed by the sexual revolution of the 1960s and 1970s, so too did John Hughes re-inscribe that domestic ideal of remaining within the ruling confines of the family, of continuing to be Daddy’s girl,” Ann DeVaney wrote in the essay collection Sugar, Spice, and Everything Nice: Cinemas of Girlhood. “In safe bedrooms, kitchens, school hallways, homerooms, and libraries, his girls act up and act out their adolescence, taking care of Daddy, wearing pink, not showing much skin, attending dances in school gyms, and being no threat to the patriarchal status quo of family or school. Hughes’s girls perform white, neoconservative teen sex roles and offer a powerful invitation to girl viewers to do likewise.” His characters were a contradiction, their non-conformity, their main attraction, ultimately subverted by a yearning to assimilate to the conventions of a decade defined by the mantra, “Greed is good.” And for those of us who were weaned on his films, it was virtually impossible not to be indoctrinated. “There were so many things in [Sixteen Candles] that were horrifyingly and politically incorrect,” says Haviland Morris, one of the stars of the film. “I think John Hughes got away with so much of it because the heart in his movies was so huge.” Thirty years on, however, we’ve dropped the rose-coloured glasses, and our response to realizing he sold us out to suburbia echoes Molly Ringwald's response in Vanity Fair when he dropped her once she grew out of it. “It was very hurtful and it still hurts.”

*

John Hughes grew up surrounded by women and money. As a teen in the ‘60s, he and his three sisters moved with their parents to a wealthy suburb of Chicago where the variation in lunch money was divisive. “I always thought that was sort of tragic, and I still do, that for certain people things over which they have no control affect their lives,” Hughes said. In an essay for Zoetrope: All Story, he confessed that the “dark side” of his “middle-class middle-American suburban life” was nothing more than disappointment. “It bothers me if even one person comes out of that theater and says ‘John Hughes is a jerk because I paid $7.50 and look what I got,’” he told The New York Times in 1991. As a teenager he was a disappointment not only because he wasn’t as rich as the trust funders, but because he was an arty kid in a jock school. Feeling like the perpetual outsider, his first success was marrying the school’s ultimate insider, blond cheerleader Nancy Ludwig. His second success was building a family with her, and his third was supporting them by becoming an ad man. “It was the only way I could keep my wife and kids in food and heat,” he told the Chicago Tribune, “while still being somewhat of a writer.” “Somewhat” was an understatement: Hughes was famous for his prolific output, juggling marathon sessions writing humour for the National Lampoon magazine and, later, screenplays, with his day job and dad duties.

Early on Hughes became a fan of Frank Capra, the Republican filmmaker who embodied the American Dream. “He had this Rockwellian version of America,” Diamond says of Hughes, “but kind of also with the whole baby boomer, a little rebellion is fine, it’s natural, kind of thing.” No wonder he supported Barry Goldwater, the Republican Party’s nominee for president in 1964, who was economically conservative, but socially liberal. “From kind of a more left leaning mentality for a Republican, people gravitated towards him and got indoctrinated into the Republican party,” Diamond explains. “I think a lot of people who were free thinkers or artists or whatever got into him and their politics evolved according to how that party went.” Michael Weiss memorably called out Hughes’s conservativism in 2006 in a Slate piece titled “Some Kind of Republican.” “Hughes’ own coming-of-age was characterized not by the egalitarian zeitgeist of the '60s but by a funk of jealousy for what the Joneses had and the Hugheses did not,” he wrote. “The polite term for this gentle rightward shift when it happens to artists and intellectuals is embourgeoisement.”

Hughes bought into the lacquered lie of the wonderful life.

On the 30th anniversary of The Breakfast Club, Hughes’s former National Lampoon editor, P.J. O’Rourke, referred to Weiss’s piece in a Daily Beast article about his friend’s politics. He explained that the two of them opposed the belief that “America itself was a flop and that America’s suburbs were a living hell” and considered the family “the fundamental building block of society” (which is why so many of the kids in Hughes’s films blamed their problems on their parents—Hughes did). There was a reason none of Hughes’s teens were real rebels, but rather outsiders with an eye on upward mobility. “The total abolition of authority and institutions would be a tragedy,” O’Rourke wrote. “If you get rid of all authority and institutions, worse authority and institutions arise in their place.”

Hughes bought into the lacquered lie of the wonderful life, that no matter your circumstances, the system allows you to succeed if you put in the work. And success is not so much independence as it is wealth and power. The heroines in both Sixteen Candles and Pretty in Pink end up with boyfriends who are richer, more popular and supposedly better looking than them. And by conforming to conventional beauty standards, The Breakfast Club’s outcast ups her social cachet with a popular athlete (while the older kook in Pretty in Pink bags a rich husband). As Weiss wrote, “[Hughes’s] portrayals of down-and-out youth rebellion had more to do with celebrating the moral victory of the underdog than with championing the underprivileged.” In an interview with the Times in 2004, Ringwald defended this contradiction—underdog embracing top dog—contending that the films were “Cinderella stories, and if Cinderella doesn’t get Prince Charming in the end, it’s a bit of a bummer, don’t you think?” Except that Hughes did not present his heroines as fairy princesses, he presented them as everywomen. And the moral of the story seemed to be that every woman, no matter who she is, no matter how unconventional she may be, wants to end up with Jake Ryan.

*

“He was fascinated by female adolescence and insecurity and how that manifested in behavior towards boys,” Sloane Tanen, daughter of Hughes’s producer Ned Tanen, told the Independent in 2011. For two and a half years, Hughes, who had no daughters of his own, called Sloane for tips and, at 13, she became the test audience for Sixteen Candles. Perhaps to thank her, the filmmaker later used Sloane’s name for the title character’s girlfriend in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. “He really wanted to know what I was into and what I liked, who I was dating and how it was going,” she said. Then there was his pen pal, Alison Byrne Fields, who, following his death, published a blog in which she revealed Hughes once told her she had received more letters from him than “any living relative of mine has received to date”— according to The Washington Post, Fields exchanged about 20 letters with him between 1985, when she was 15, and 1987. Hughes told her he often used the argument “I’m doing this for Alison” to justify his decisions to Hollywood. But his number one girl would always be Molly Ringwald.

“When you hear a lot of people talk about how John Hughes respected teens,” Diamond says, “I think it really stems a lot from Molly first.” Legend has it that Hughes’s work at the National Lampoon—which attracted Hollywood attention—got him into the International Creative Management talent agency where, in pre-production on The Breakfast Club, he received a stack of headshots of their clients, including Molly Ringwald. “From what I heard from him, he put my headshot on the bulletin board by his desk and wrote Sixteen Candles over a weekend,” the actress told VF. “And when it came time to cast it, he said, ‘I want to meet her: that girl.’” But Hildy Gottlieb, Ringwald’s agent at the time, remembers it differently. Her boss, Jeff Berg, represented Hughes and asked Gottlieb to help his client cast his films. “I met with John, he gave me a shopping bag full of scripts,” she says. Gottlieb ended up reading two: Sixteen Candles and The Breakfast Club. “I said to John, ‘This young girl [Ringwald] would be great in these, why don’t you sit down with her? So he did.”

Hughes liked Ringwald immediately. “She was a real kid and she had a sense of that,” he told the Fort Lauderdale Sun Sentinel in 1986. “She hadn’t grown beyond her years.” Pretty in Pink producer Lauren Shuler Donner thinks he also liked how unique Ringwald was. “She was very much her own person,” she says. “She wasn’t like the other actresses in Hollywood—she didn’t look like them and she didn’t act like them.” Marilyn Vance, the costume designer on all of Hughes’s teen films except Sixteen Candles, concurs. “She wasn’t your average pretty young girl,” she says, and her maturity wasn’t average either. “She was more sophisticated for so young. She had an attitude.” That Ringwald wasn’t the “perfect, perfect beauty” was a particular boon, according to producer Michelle Manning. “There really weren’t a set of films that kids felt really spoke to them not at them,” she says. “I think with her specifically, there was a quality about her that he felt girls could relate to.”

“The kiss is the most beautiful moment.”

Ringwald’s hair wasn’t blond—she dyed it after seeing Anita Morris’s “mass of fiery red” on Broadway in 1982—nor was it long. “I had realized the futility of trying to look like what passed for beautiful in Southern California in the early eighties,” she wrote in her 2010 memoir-cum-lifestyle guide, Getting the Pretty Back. A portrait Ringwald recently tweeted from the ninth grade, pre-Sixteen Candles, shows a kid who skirted the decade’s “High Femininity”22“In fashion terms, the backlash argument became: Women’s liberation has denied women the ‘right’ to feminine dressing;” wrote Faludi. Designers retaliated with an onslaught of hyper cutesy pinks, ruffles and poufs. with a mix of pink and black—pink pearls, pink glove, pink sash, black boots, black shirt—Madonna crossed with Michael Jackson. “I dressed from my imagination,” she wrote, “sometimes in my excitement, I couldn’t just choose one thing—so I layered.”

Ringwald started acting on stage at age five and a year later she had appeared on a jazz album with her father's band. After a brief stint on television—Diff'rent Strokes, Facts of Life—her first film came along in 1982, Paul Mazursky's The Tempest, for which she was nominated for a Golden Globe. Being a professional at 13 seemed natural to her. She had grown up with a stay-at-home mom who felt “obsolete” and encouraged her kids to do differently. “It was always the idea that you will take care of yourself. You will never need a man to take care of you.” Ringwald told The Los Angeles Times. “It was drummed into my head.”

*

A teenager is invisible to both her family, who forgot her birthday, and the boy she’s in love with. It could be the plot of any number of B-movies that made up the post-Porky’s youth flick boom of ‘80s America. “What makes Sixteen Candles different is that this film looks at teenage love in an entirely new way—from the girl’s point of view, which is untouched territory as far as Hollywood is concerned,” Hughes told the Chicago Tribune in 1983. It was a surprising boast considering Sixteen Candles came two years after Amy Heckerling’s Fast Times at Ridgemont High, which circled the sex life of a female sophomore played by Jennifer Jason Leigh, and a year after the Martha Coolidge-directed Valley Girl starring Deborah Foreman as the eponymous adolescent. Perhaps Hughes meant he was the first male Hollywood filmmaker to touch the teen girl experience.

Samantha Baker (Ringwald) wants a “platinum” birthday with a “pink guy” (not a black one)33Sam’s best friend expresses shock when she mishears her saying she wants to date a black guy. This scene and many others in his films resulted in Hughes being criticized for whitewashing America on screen. “I’m not going to pretend I know the black experience,” he told the Times in 1991. “Maybe I’ve been wrong, through short-sightedness or whatever. But I’ll get there.” , a Trans-am and STD-free sex on a cloud. Jake Ryan, the pink guy in question, drops his white-hot girlfriend Caroline Mulford (Haviland Morris) after noticing Sam looking at him like she’s “in love” and finding a note in which she names him as the person she’d “do it with.” He wants “more than a party,” even though Caroline’s fantasy—“I’m your wife, and we’re the richest, most popular adults in town”— isn’t that different from Sam’s. Jake wants to love a girl who will love him back, but it’s unclear whether Sam is in the position to do that (her summary of him: “Jake is this senior and he’s beautiful and perfect and I like him a real lot.”) She’s less conventional than Caroline, yet she wants a guy who is conventionally superior—older, richer, “hotter,” more popular. Caroline is equally hot, rich (presumably, though we know less about her than Jake) and popular, but she is “careless.” She does not deserve Jake, Sam does. “You know when you’re given things kind of easily, you don’t always appreciate them,” Sam’s dad tells her. “With you, I’m not worried.”

The trouble with Watts, who Hughes called one of his “best characters,” is that she is ultimately defined by Keith. “It was an attempt to see if the geek could get the girl and work,” Hughes told The Hollywood Reporter. And the way he gets the girl is, of course, through an Allison-style makeover that masks her edge. Watts covers her tattoo and puts on lipstick, a bra and a form-fitting black silk outfit (at least it isn’t pink) and takes out her punky row of earrings. In the final scene Keith chases after this feminized version of his best friend as she walks blubbering down the street and kisses her—lifts her off the ground, no less—then hands her the diamond earrings he bought Amanda with his college money.

Watts: I wanted these, I really wanted them.

Keith: You look good wearing my future.

In an earlier version of the script, Keith reportedly proposed as well, but the final shot was bad enough. In an interview for Some Kind of Wonderful’s EW reunion in 2012, Masterson was still frustrated by it. “All anyone says to me a quarter of a century later is, ‘I love that part where you get the earrings,’” she said. “It’s weird! This materialistic aspect is not who Watts is. She would have walked away victorious, and then to the pawnshop.” Alyx Vesey at Feminist Music Geek wrote, “I do think there’s a valid argument to make for how heterosexuality may contain and stabilize Watts and thus render her as less of a threat.” And a threat she is, not just sexually, but to traditional femininity. “Watts is grouchy, snarky, tough, insecure and sometimes downright mean,” Kate Harding said in Salon in 2009 in a piece about Hughes heroines. “She has no knack for the sort of performative femininity that helps Amanda Jones (Lea Thompson) transcend her wrong-side-of-the-tracks background among the rich and popular, so she can only deflect their derision with an endless supply of snappy comebacks—and, often enough, snappy pre-emptive strikes.”

Some Kind of Wonderful only made $18.6 million when it was released in 1987, the lowest box office for a John Hughes film at the time (for comparison, Sixteen Candles raked in $23.7 million, The Breakfast Club $46 million and Pretty in Pink $40.5 million). It’s apt that his attempt at subverting convention announced the death of an oeuvre that often upheld it. That the one film in which the fairy tale ending does not involve the oddball playing ball with the richest, hottest and most popular alternative did not sell out. Hughes had disappointed an audience that had acclimated to the Reagan era’s acquisitive anti-feminism. It follows that, in recent years, these movies, in which he presented women within the ‘80s male paradigm, have inspired predominantly male directors (Kevin Smith, Todd Phillips, Judd Apatow, David Dobkin at al.) The final scene of Sixteen Candles warned us:

If you were here

I could deceive you

And if you were here

You would believe

And we did. But not anymore.