On the morning of my surgery, I wake up at 5 a.m. in Laval. Outside my window, the city is dark and coated in a heavy snowfall. The temperature is -14, a biting cold that seeps through the walls of the surgery clinic’s guest house. The room I’m sleeping in is painted a deep blue. In the reflected glow of my phone’s LED screen, the walls loom around me like an indigo womb. I get dressed in darkness.

I go outside, order an Uber and head to the nearest twenty-four-hour convenience store. The driver is confused by my early morning adventure. He calls me “mademoiselle” and seems worried about my safety in the still predawn neighborhood. The radio is tuned to a classical music station, so Samuel Barber’s “Adagio for Strings” fills the car as we cross the bridge between Laval and Montreal. I try to look for the river, but it’s too dark to see anything but the car’s interior lights.

We arrive at the convenience store. I get out and the Uber drives away. I buy cigarettes and smoke one in the parking lot. I order another Uber to go back to where I’m staying. The same driver returns to pick me up. He seems more concerned now. He tries small talk but I don’t speak any French and he only speaks a little English so we shrug at each other. When I get out of the Uber, he says, “Have a good day, mademoiselle,” and shakes his head at me. I wave as he drives away.

I stand in the snow and smoke again. Dawn fills up the horizon. I am not thinking about surgery. I’m not thinking anything. I’m empty like the spaces between the houses and the sky. Snow, cold, and wind move through me. I disappear from everything until I go inside and start packing for the hospital. When I remember this moment later I’ll feel like a part of me is still smoking at dawn in Laval, waiting to be completed.

*

I want to hold space in my story about surgery to say that there are many ways to be a trans girl. For some of us, surgery feels like the only option for happiness. There are many trans girls who never want surgery and find joy in their existing bodies. I know several trans girls who are caught in the middle, trying to decide what path is right for them. The current approval system for surgery requires you to pretend that you know exactly what you want, but there are very few moments in life without hesitation or doubt. Wanting something you’ve never had, especially with a lack of information or supports around your decision, is a difficult truth to articulate.

I started my transition thinking that I wouldn’t take hormones or have surgery but I changed my mind. An important part of my transition was learning to embrace my femininity and accept that it was possible for me to change my body. I decided to begin hormones because I cried when my doctor rescheduled my initial consultation appointment—the thought of waiting two additional weeks to even discuss hormones reduced me to tears. The further I went into my transition, the more I wanted for my body. I still remember taking my first testosterone blocker, a small white pill in the palm of my hand that tasted like chalk.

After eight months on hormones, I began the process of seeking medical approval for surgery. I went through the interviews and the health checks. I packaged my forms and emailed the clinic in Montreal until they gave me a date. The current surgery regulations require you to have been on hormones and to have lived full-time as your gender for at least a year. I got my surgery date within four weeks of being eligible, a record for any trans woman I know.

As I got closer to my surgery, I was bombarded with negative messages on social media and in person about my future vagina. Transphobia and its allies spread an enormous amount of misinformation about gender reassignment surgery—that we’re crudely chopping off our penises, that our vaginas are just open wounds that never heal—that creates a falseness around our possible bodies that feels like a heavy weight. Miseducation about gender reassignment surgery is a barrier to trans women seeking care and access to a procedure which recognizes our basic humanity.

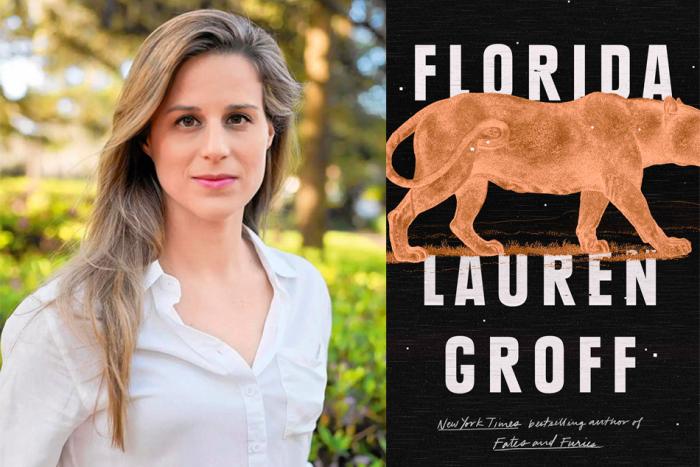

I believe that gender reassignment surgery is a right but I didn’t know what surgery would mean for me. Images of post-op vaginas from my surgeon are hard to find. Even my friends who’d had the procedure couldn’t really explain what would happen, so I made my decision without proper information about possible outcomes. I’m writing this essay to offer a small window so that other trans girls have more information than I did.

There are many contradictions in my story, complexities that I can’t reduce into words. I don’t need my story to be perfectly clear, a streak-free window into my humanity. There are parts of myself that I refuse to show anyone. Society demands that trans women explain ourselves before we’re allowed the right to be called women, but I’m tired of explaining something that isn’t yours to understand.

My vagina wasn’t created on a surgeon’s operating table. It grew inside me throughout my life. Surgery was a way to bring it into physical being, but it marks the middle of a process, not the beginning or the end. My body and gender are continuous. It was neither created nor ended by surgery, but reimagined. I am a living woman and this story is a record of my living.

It is as messy, as incomplete, as flawed as I am.

*

I sit in the waiting room on a black sofa. I am minutes away from entering the operating room and about to meet my surgeon for the first time. The walls of the room are painted black. The light from the lamp barely illuminates the far corner of the room. I can see my reflection in the mirror across from me. I compulsively stroke my hair over my ears, trying to smooth out my curls. I want to look as feminine as I can when I meet the surgeon. I want his best work. I’ve learned men only give you their best when you look worth it.

I don’t know how long I wait in the empty dark room, but it is long enough for me to start shaking from the cold air. My surgeon abruptly enters, walks over and introduces himself. Something in his eyes reminds me of my partner, W, a contained intensity. He takes me into a small examination room and has me open my gown to show him my penis. He looks for five seconds and declares that I have “lots of skin to work with.” He asks if I have any questions.

I tell him my partner’s penis is seven inches and I need enough depth to accommodate him. I say I want a nice clitoris. I realize as I speak that I’m high from the medications that the nurses gave me. I want him to know that I have penetrative sex with male partners. I’ve heard stories that lesbian trans women are treated differently at the clinic and have worse results. I want him to think that my surgery will matter to some unnamed man’s pleasure. I say everything in my softest voice, flirting, casting my eyes downward and back up, playing shy.

He smiles at my flirtations. “You realize you don’t need to have all of the penis inside you, right?” he says. “But I’ll do my best.” He places his hand on my right shoulder for several seconds, stroking up and down, then leaves the room. Our surgical consult has taken less than two minutes. A nurse comes to lead me into the operation room, a giant room filled with medical equipment and people in blue lab coats. No one acknowledges my presence in the room, as if I’ve walked into a stranger’s birthday party.

The anesthesiologist has me climb onto the operating table and inserts my IV line. A nurse starts the spinal block which cuts off sensation from my lower body. The anesthesiologist tells me that I won’t remember anything after this moment, but I do. I remember them moving my legs into automated stirrups which lift me up into the air. They move a metal frame around my chest and drape it with a white sheet so I can’t see my lower body anymore.

In fragments that come back to me slowly over the next two days, I have the image of the surgeon coming into the room. I can recall him begin to touch my genitals, moving my penis around while speaking to the nurses. I know I woke up during the surgery and cried out. I can see the anesthesiologist pressing his arms down over my chest, staring into my eyes and telling me to stop moving. He says to focus on him while a nurse frantically injects something into my IV line. I remember his bright blue eyes, the weight of his arms on my chest, and the white sheet moving in the ventilated air of the operating room.

These are the opioid dreams of my becoming. They still haunt me.

*

I always knew I would have this surgery someday. I’ve been talking about it since I was a child. I had lived my entire life wanting something I’d never had, dreaming of the possibilities in my body. Other trans women use different ways to talk about this wanting. They say “fixing a mistake” or “aligning my body to my mind.” I use the word “miracle.” For all the times I’ve prayed to wake up in a different body, surgery would finally answer me back.

People imagine their bodies as a certainty. They grow up knowing what each part does, naming it as their own. Absolute containers, permanent fixtures. We are born into our bodies and can’t escape them until we die. I don’t like this understanding of our bodies—it doesn’t correspond to reality. We get sick or injured. We change weights or heights. We modify our bodies with tattoos, piercings, and other bodies. We are not born into one shape, but many.

My body is a conversation. It started when I was born, but there were mistakes made. People didn’t listen when I told them that my body wanted to change. No one asked me what I was, only assumed they understood my body better than I did. For most of my life, I listened to what other people told me. I accepted their limitations of my body. I tried to make my body thinner and stronger, using it to pleasure others in exchange for love. I starved myself and ran forty miles a week.

My body broke through the denial. It demanded transformation. My thighs and breasts wanted to grow. The curve of my hips needed to reach out into the world. My body stopped listening to everyone else and told me who we really were. For the first time in my life, I listened to my body and its joy. I took hormones and sought surgery. My body and I let ourselves change.

I surrendered my certainty and safety. My body held me when no one else did. Together, we imagined a possibility instead of an ending. This is the real story of bodies. Movement, joy, and release into new configurations. Our bodies do not need to be perfect or exactly as they were when we were born. We are not ruled by the shape we arrive in. We adapt, heal, and expand. Our bodies are not an ending, but a beginning. This is a truth I am willing to die for.

*

I wake up in the recovery room. I can’t feel anything below my waist. I drift in and out of sleep for hours but wake up when a nurse comes in to check my dressing. Sensation starts to return to my body and it hurts now, a dull tight ache between my legs. She starts to chat with me about her love life, telling stories of her boyfriend while she injects my IV line with morphine. I like her instantly. She discovers that my dressing is leaking blood, a sign that I have active bleeding. It’s a risk, she tells me, and she has to repack the site. It’s painful, so much so that I start to cry even with the morphine.

I text W to distract myself from the pain, saying that I’m okay but still bleeding. I say how happy I am. As I type out the text, I realize it’s true. I can’t feel much, but I can feel that my penis is gone. The space between my legs is different now, lacking a small weight I’ve carried since birth. I’m free, I think, I’m finally free. W texts back a long line of fucks with exclamation marks. He says to keep him updated. I text him on and off again throughout the night, delirious with joy and medication.

Right before I fall asleep again, I text him, “I have a vagina!!!!” He texts back, “yay you have a vagina!!!!” The ordinariness of our texts is contrasted by the bizarreness of the moment. I’ve spent two years talking to him about wanting this surgery. Once I sent him the only picture of a post-op vagina from my surgeon I could find and asked if it looked normal. This surgery is entirely my own, but it’s been a shared goal between the two of us for as long as we’ve known each other. Now he witnesses my becoming from an anxious distance, celebrating something we didn’t think was possible.

I feel the space between my legs, tight and hurting. The nurses have packed ice around my dressing site. I think about how my morning started, alone in a blue room and traveling through a darkened city. The hospital room is bathed in the same blue glow of machines and distilled light. I’m here, I think, I’m alive and I have a vagina. It feels like coming home after a long trip to somewhere you never wanted to go.

*

In the week before my surgery, I’m consumed by a constant anxiety. I lie on my bed and stare at the ceiling. I cry in the shower. I stay up all night listening to gospel music. I disintegrate into worry and doubt. I escape into the Ativan my doctor prescribes me. It softens me into water and lets me sleep.

W and I hang out on the Thursday before I leave Toronto for Montreal. My relationship with him has always been marred by intense highs and lows, with sometimes violent transphobic interactions, but in the time before my surgery, his love holds me together. I meet him on campus at his grad student office. We order bad Chinese food with neon red dipping sauce. I introduce him to chicken balls. We sneak out of the anthropology building to smoke and end up wandering the deserted campus, leaping through bushes. I pelt him with loose snowballs and chase him with cold wet hands. He walks me to the subway and I go home.

When I get to my apartment building, I realize I’ve lost my keys. I call W and apologize. We meet up at Spadina station to retrace our steps. He isn’t mad at me, just kind and sleepy. We listen to music with his headphones while riding the streetcar back to campus. A sad guitar love song plays in my left ear while the bright lights of the streetcar make me blink. We check everywhere on campus but can’t find the keys. It’s too late to call my landlord so I go home with W.

We ride to W’s stop in a shared tired dreaming. He touches my hair on the subway ride, flicks it with his hand and says how long it’s gotten. I smile and shrug back. W has known me since I was a boy, back when my hair was sheared short in the classic young twink gay haircut. Now my hair is shoulder-length, blonde, and curling at the bottoms. This moment of small intimacy is more powerful than any other, how it shows his love of me through my many transformations.

We get to his house and climb the stairs to his upper-level apartment. I wander through his room, picking up scattered photographs and papers on his dresser and desk. I lay on his bed and stare at the ceiling. W gets out his vintage camera, loads it with film, and lies beside me. “Let’s take a photo to remember this terrible night by,” he says, holding his camera above our heads. We look into the camera together and he clicks it shut. I want to have the photo, even though I think it won’t turn out. It’s one of the last moments of me in this body and this life.

In the morning, he reads me poetry in Spanish and makes eggs. It’s raining as we leave his house, so I open up my umbrella. My keys tumble out onto the ground. They were jammed inside the folds of the umbrella. I try to apologize to W but he shrugs it off. We ride the subway back together. He goes to school and I go home. I feel happy as I walk through my door and into my apartment.

Something in this night holds me completely, lingers in my body throughout my surgery and into recovery. I take it as a small miracle, one of the moments I’ve been chasing since I transitioned. The everyday moments when I forget I’m trans. Where I feel ordinary and small but safe inside an intimacy I trust. Not alone, not othered, but held and possible. When I lie awake in my hospital bed in pain or when an overwhelming depression sinks over me, I think about this night to remember why I’m having this surgery.

Perhaps the two things, being loved and having surgery, seem unrelated to someone who isn’t trans. How many times in your life have you read about a girl like me being loved? How many times have you heard about a trans woman being read poetry in Spanish by her lover in a sunlit front room? How often do you see a trans girl falling asleep on a boy’s shoulder in the subway at 1 a.m.?

What about a harder question: How often do you think about a trans woman’s genitals? When you see a trans woman on the street or in photos, do you find yourself wondering what’s between her legs? When you read about a boy loving me, do you assume he’s gay? How frequently does the thought of my genitals slip into your mind when you look at me or hear me speak?

Being loved and having surgery are linked for me, because the possibility of one relies on the other. I want to live a life where I don’t have to write an essay about my genitals or wonder what you’re thinking when you look at me. I don’t want to kiss a boy’s forehead in the morning when I wake up and worry that he’s afraid of his roommates realizing I slept over. I want to stay inside a moment of being loved as long as I can. Surgery doesn’t stop transphobia and is not a solution to the shame people place on trans women, but it does let me be present in my body without feeling an overwhelming sense of discomfort.

I want to be a girl who can get undressed with a lover without feeling like she needs to apologize first.

*

After two days in the hospital, they move me and my roommate to the aftercare clinic. The clinic is attached to the hospital, a modern two-story house named after a butterfly. I am too weak for the five-minute walk over to the clinic. Every time I stand up, I have a rush of dizziness and almost faint. A support worker takes me over through the snow and ice in a wheelchair. When I arrive, two nurses walk beside me with their arms interlinked with mine to get me upstairs and into my room. They give me painkillers as soon as I reach my bed.

I lie in silence in my new room at the clinic. My bed faces the large double windows. I can see the tops of trees in the window and the skyline. Large airplanes come and go constantly, close enough that I can make out the airline names on the planes. The airport is close to the clinic. Watching the planes descend across the skyline becomes my comfort there, something I do when I can’t sleep or feel overwhelmed. They remind me of life, how everything is in motion and possibility still exists.

My time in the clinic is dictated by a recovery schedule set by my surgeon. Breakfast, lunch, and dinner are served downstairs at set times. Nurses come and go to check our vitals and give us pills three times a day. There are eight other girls in the clinic, all recovering from the same surgery, and one trans man. It takes me two days to start talking to the other patients but soon I become integrated into the social life of the clinic. We are a range of ages, backgrounds, and races.

Everyone reacts differently to the surgery. Some girls have complications and struggle with pain. Other girls have no complications and seem to be without pain. I turn out to be one of the most active girls, moving around the clinic constantly and going for walks outside. I am rarely in my room, preferring to sit on the coach in the downstairs common area. My roommate spends her time sleeping or laying silently on her bed. I find the room suffocating.

I have visitors almost every day. One of my friends in Montreal, another Indigenous trans person, hears that I’m staying in the city while recovering and sends me visitors from their social network, including their partner. My best friend’s wife, K, comes over every day, chatting with me and offering a gentle support. Two of my writing friends visit as well, one of them wearing a long black fur coat that raises the eyebrows of the nurses. I rely on these visits to survive, a thread back into my life.

Other people can only support me so far. I’m ultimately alone in my recovery. Against the advice of nurses, I go for walks outside of the clinic, shuffling over ice and snow to stand close to the river. There is an endless rhythm of dilation, showering, pain medication, and meals that fills up my time. Of all of these tasks, dilation is the most complex. During surgery, the surgeon cut through the muscles of my pelvic floor in order to make space for my vagina. I have to re-train those muscles, unused to being opened and flexing, by inserting brightly coloured cermanic dilators into my vagina and holding them inside me for thirty mintues.

In the rare moments when I am not doing anything, I try to process what is happening to me. Everything feels ordinary, but my body and life are permanently altered. There’s a complexity to my surgery which I don’t know how to say aloud. I imagined it would hurt more or that my life would suddenly swell with emotion. Sitting in the front room as the sun rises, I realize that I thought the surgery would change me, but why would it? I’ve always been a woman. The only difference between me now and the girl who walked into the clinic a few days ago is what’s between my legs.

It is a difference that matters, both to me and others, but it isn’t the ending or beginning of my gender. It’s just another moment in learning more about who I’ve always been.

*

On my third day at the clinic, they remove the dressing from my vagina. I haven’t been able to see my vagina since the operation because of the blood-soaked gauze covering it. I sit on a medical examination table with my feet in stirrups. I hate this room, the sudden vulnerability of being naked and having my genitals exposed to the cold air. The nurse cuts away my dressing and uses tweezers to pull out the gauze. She tells me that they really packed my vagina tightly in order to stop the bleeding. It’s over in minutes.

I walk back to my room. I still haven’t seen my vagina because the swelling of my pubic mound prevents me from seeing between my legs. My vagina starts to burn, a sudden increase in pain as the blood rushes back into tissues that the dressing had compressed. The pain overwhelms me. My roommate is in the shower, having had her dressing removed before me. I stand at the window, overcome by pain and the strangeness of the moment. I open the window, just a crack, and start to cry deep shuddering cries as tears run down my face. I don’t know what to do, so I just stand at the window and cry.

My roommate comes out of the shower and hears me. She asks if I’m alright and I tell her through sobs that I’m fine. The pain is immense, the worst it’s been since they repacked my vagina after surgery. I stop crying and put on clothes. I go downstairs and ask for pain medication. The nurses try to resist me, but I insist. I go back upstairs and take the first shower I’ve had in five days. There is a mirror in the bathroom. I stand naked in front of it and see my vagina for the first time.

My vulva is perfect. It’s swollen and bruised. Long lines of black and purple radiate out across my hips. I can see stiches around my clitoris and sutures lining the entrance to my vagina. I’m surprised at how ordinary it is, despite the obvious trauma of surgery. It looks like an everyday vagina that’s been in a bar fight. It fits my body as if it was always there. I stand and stare at my naked body for five minutes, shivering in the cold bathroom.

*

When people talk to me about my surgery, they usually want the graphic details. Some of my friends watched videos of the surgery online before I went. People are shocked and excited to hear about my vagina, strangely fascinated by the medical procedure and its outcomes. I resist talking about the details because it presents the surgery as an otherworldly event. In reality, the surgery is highly standardized, having existed for more than forty years.

Part of the misinformation about the surgery is a fundamental misrepresentation of what the surgery does. There is a shroud of secrecy and discomfort about trans women’s bodies in general, and the surgery in particular. People email me and ask for pictures after surgery. They ask how much depth I have or what my clitoris looks like. When I challenge them on asking for such personal information, they are surprised to discover that I don’t want to share my body with them.

While increased representation of trans women in media has contributed to a greater awareness of who we are, it also turns our lives and bodies into museum exhibits. Our rights and humanity are debated in the news while our deaths become sordid tabloid articles filled with misgendering and hate. Our bodies never belong to us. With my vagina, I promise to myself that I will try to protect it from anyone’s voyeurism or curiosity.

After enduring so much pain and fear to have a vagina, I want something more for my body than exposure. The world may not let me have what I want, but I intend to try my best to keep myself safe. My vagina is sacred to me. It represents a vulnerability and a joy I don’t want to lose. It is more than a teachable moment—it is my humanity, a living and breathing organ that is worth more than your fascination.

*

I make it through the six days of recovery in the clinic. They send me in a taxi to the airport at 7 a.m. I’m so weak that I can barely walk to the cab. I almost throw up on the ride from the clinic to the airport. I’m traveling home alone, something I realize is harder than I expected. At the airport, I check into my flight and the attendants put me in a wheelchair. They seem to realize what’s happened to me even though I don’t say anything. They wheel me through security and take me to my gate. I wait for an hour in the wheelchair before boarding the plane.

The plane ride home is a blur. I medicate with my painkillers in order to handle the discomfort of the plane. I feel every movement as sharp pains between my legs. My friend from the trans support group I attend meets me at the airport. He takes me home in an Uber. We eat cheeseburgers on my bed before I fall asleep from the painkillers. When I wake, I start the rhythm of recovery which will structure all of my days for the next three months. I wake up, I take pain medication, I dilate, and I take a bath. Rinse, repeat.

Recovery is difficult because I float in my apartment alone. I take my medications and dilate when I’m supposed to. I try to eat, but struggle to eat more than one meal a day. People come over and leave. My relationships struggle to handle the strain of my recovery. I try to not ask anyone for anything. My pain medications make me emotional. W comes over one night and I end up crying on him, saying how hard it is. He tries to comfort me, but there’s only so much of my anxiety that he can hold. I push myself to become stronger.

I spend three months on narcotic painkillers. They warp time around me. Each time I take another dose of Oxycontin, I feel more disconnected from my body and its healing. I need the medication to dilate and to sleep, but it drains me in ways I don’t realize until I’m off it. I worry about becoming addicted. Each time I take a pill, I feel guilty and ashamed that I still need them.

I cry in my shower when new drops of bright blood fall between my thighs. I have less bleeding than other girls in recovery, but I still panic whenever new bleeding starts. I worry about my healing constantly even though the doctors tell me that it’s fine. I sleep under one blanket, imagining another life for myself. Maybe new things will come in the spring. Maybe I’ll find my way back into the everyday intimacy I want.

*

Two months into my recovery, a bad Crohn’s flare sends me to the hospital ER by ambulance. The intake nurse refuses to use my female name, tracking down my old male name in the hospital records. She calls me by a male name that I haven’t used in years. Even though my health card has my correct gender and name on it, she challenges me about my gender while I’m vomiting on a stretcher. She and the male paramedics joke about my surgery and my vagina. She asks them if they looked at my vagina to see if it looked like the “real thing,” teasing one of the paramedics that he’s into freaky stuff so maybe he would get a rise out of looking.

Throughout my time in the ER, no one uses the right pronouns or name. They send me for diagnostic imaging. The doctor comes back and asks me what my vagina is. He points to the image of my torso, drawing a circle around my vagina as if it’s some unknown foreign object. No one understands what gender reassignment surgery is or if it’s complicating my Crohn’s disease. I’ve been vomiting for twenty-four hours now, unable to drink or eat and in intense pain. After much confusion, they release me back into the street.

I end up in two more ER departments over the next week. At a different hospital, an ER doctor asks me if I’m a sex worker or addicted to drugs because I’m trans. I am still misgendered and treated as a man. They refuse to run tests on me or treat my pain, despite my continued vomiting and weakness. Male nurses and doctors expose my vagina and breasts to strangers in the hallways. No one asks me if I would prefer a female nurse or physician. Eventually, they move me to a hallway and I just leave.

The final ER department that I visit listens to me and uses my correct pronouns. They treat me and do more imaging. No one understands my surgery or my vagina, but they take care to respect my body. I’m in the waiting room for seven hours. My best friend, another trans girl, stays with me and holds my hand. She advocates with the nurses and doctors for me. At 3 a.m., the doctor tells me that I have a partial bowel obstruction and need to be hospitalized.

I spend the next five days in the hospital. I am unable to dilate because most of my time is spent lying in a hallway on a stretcher. W visits me and explains to the nurses that I need to dilate in order to maintain my surgical outcomes. The nurses come up with a solution by letting me dilate in a closet while one of them stands guard outside the door. After a week of being extremely ill and having my body dehumanized by strangers, I feel more exhausted than I’ve ever been.

Somehow, I recover and survive. My body knits together, reshaping itself back into a unified whole. I go back to work and move on with my life. Finally, after a lifetime of waiting, I’m here in the world as myself. Nothing is really different, except the quiet voice that raised alarm bells every time I encountered my body before surgery is finally silent.

It takes me three months of recovery to feel comfortable touching my vagina. Despite caring for it every day, I remain disconnected from it until I force myself to touch it. It is not a wound nor a scar. It is a soft and warm space inside me that is filled with pleasure and love. After so much struggle, my vagina is so ordinary that it shocks me. I forget about the difference in my body, mindlessly dressing in tight leggings and buying pads at the drugstore as if it’s always been my life.

*

The night before I leave for Montreal for my surgery, W and I go to see Call Me By Your Name. We don’t really like the film but we do enjoy the popcorn. He brings Milk Duds and Twizzlers, a working-class American gesture I love. We go for tea afterwards in the trendy café by my apartment. He holds my hand across the table, squeezes it while I tell him how scared I am. I ask him if I should cancel my surgery. “You don’t have to do this,” he says, “I’ll still be here either way.” I smile and squeeze his hand back. “I know,” I say, “but I feel like it’s the only way I’ll ever be free.”

He stares into my eyes before answering me. “I don’t know what the surgery will change for you,” he says. “I can’t know what it’s like to feel the way you do.” I don’t know what to say, so we just sit with the fear moving around me. He traces his fingers down the length of my arm from my palm to my elbow before returning to hold my hand again. I want him to say or do something that will make me feel less afraid but I know that this surgery is something I have to face for myself. He walks me home and holds me in my apartment lobby. I press my face into his neck, wrapping my arms around him as tightly as I can. He sways with me for more than five minutes.

When he lets go of me, I lift my hand up to his face and run my fingers down his beard to his lips. “I love you,” I say, terrified that it’s the last time I’ll see him. A sheepish smile slips over his face before he replies, “I love you too.” He walks away into the night. I go upstairs to my apartment and stare at my packed suitcase. I call a friend and talk to her before going to bed. I think about how much my life has changed since I transitioned. I’ve made a different life and now I’m uprooting it again for another change.

As I fall asleep, I imagine coming home with a vagina. I imagine going to school to my new PhD program in tight leggings. I imagine spring and going to a lake in a bathsuit. I imagine myself happy and loved. I imagine feeling comfortable in my body. I hope for a better life and with that hope, I decide to have this surgery, whatever the cost may be.

*

Surgery is sometimes presented as way to escape being a trans woman. I know of trans women, more cis appearing than me, who’ve had their surgery and never identify publicly as trans again. A part of me longs for the freedom of disappearing into an “ordinary” life. To not face transphobia and its constant violence, to not worry what my lovers see in me, to not fear attack and criticism because of my gender.

Surgery was not an escape for me. I have a vagina and a body that aligns with society’s expectations of a woman, but I am still a trans woman. Even if I disappeared, going “stealth” as it’s commonly called, I would carry the scars of my transition inside me. I would also have to surrender the gifts of my transness, each moment of everyday joy and pleasure that has fallen over my skin and passed into my spirit like rainwater into the ground. This complicated being means more to me than any illusion of freedom.

I have a screen shot saved my phone. It’s a message from W to me, sent before my surgery after I let him know how worried I was. He writes, “It will be ok. I love you. I promise to help you as much as I can.” He reminds me that even if my surgery is hard or painful, it will only be for a short time. He adds, “Plus spring will come shortly after. You can grow into your vagina while all the other flowers are learning to bloom.” There’s a pink flower emoji and a bright red heart at the end.

I keep the screen shot of the message because it reminds me of an important truth about my surgery. Nothing is entirely perfect, unmarked by its passage through the world. In every love, there is the inevitability of loss. Yet as W reminds me, in every pain is the possibility for pleasure.

And in every winter, the promise of a new spring.

*

Three months after my surgery, W and I break up. The two years of our on-and-off relationship have cycled between care and abuse; his transphobia has always been present inside our love, a violence that has soaked into my body until every part of me is haunted by his ghost. I hoped surgery would resolve the transphobia and finally make him see me as a real woman. It doesn’t.

When he sees my vagina for the first time, his face falls. He walks out of the room and doesn’t return for five minutes. We don’t talk about it for a few hours but when we do, he yells at me so loud that the restaurant server comes over to check on us. I cry alone in an alleyway, struggling to understand why he would hurt me in this profoundly vulnerable moment. We break up three weeks later. I can’t forgive him for this betrayal.

I’m tempted to hide the truth of our breakup. It must seem like a distraction from the story about my becoming, a disclosure that contradicts how W supported me throughout my surgery, but it isn’t. One of the most important lessons that I’ve learned from my surgery is how to accept the imperfections of our lives. Every day after surgery, I watched my vagina heal, going through stages of multi-color bruises and swelling. I bled through my sheets during nights and washed away post-operative fluids in the morning.

It has taken almost five months for the swelling around my vagina to diminish. My scars, two slightly raised vertical incision lines, cup my labia and centre my vagina on my body. There is a small red mark just above my pubic hair that shows where my post surgical blood drain was. As time progresses, my scars fade away and become less noticeable, but they will always be there, visible to me if indistinguishable to anyone else. I feel the same way about my scars around my vagina as I do about W.

The events that surround our becoming leave an imprint on us. The complexities of my relationship with W are not something I want to diminish in order to tell a better story. I can’t separate W from my surgery without denying the ways that transphobia and transmisogyny have shaped the woman I am. His love and abuse changed me as much as a surgeon’s scalpel did, leaving impressions in my body that diminish but will never fully leave me. Just as my vaginal scars identify me as a trans woman, so does the way that I instinctively flinch whenever a man touches me.

The breakup and the violence of my relationship with W almost kills me, but I survive. I move on with my life and the process of healing. I write an essay about our relationship and his abuse. New lovers come into my life and I find joy in my vagina, learning to orgasm and feel confident in my body. I support other trans girls around me as they begin to plan for their surgeries. I answer detailed questions for them about the surgery and my vagina. Sometimes, depending on how much I trust them, I share images of my results with them.

I try to remind other trans girls to believe in the possibility for our joy. Sometimes, when I touch the inward curve of my labia, I believe in it myself.

*

A body is a conversation between the past and the future. It is never stationary, but always moving towards a different way of being. What defines us as people is not the bodies we are born into nor the bodies we create, but the lives that we live through them. My life is more than my body but for the first time, my body feels like home.

Miracles happen. They come in unexpected ways. They fall from the sky or are made by a surgeon’s hands. The trick about miracles and bodies is that they require faith. I’m not talking about faith in some omnipotent being, but having faith in our own possibilities. The truth is that the hardest part of getting my vagina wasn’t the surgery nor the recovery. It wasn’t the wait times nor the complications. It wasn’t even the risks or the pain.

The hardest part of getting my vagina was believing I deserved to have one. I do. I always did and now, I have a life and body that feels entirely my own. I can’t explain to you what that means unless you’ve gone through what I have. That’s the real gift of surgery for me. Finally, after a lifetime of being told that I was wrong, I never have to explain myself to you again.

*

The apple blossoms along my street opened their fragrant petals on the same day as my first post-surgical orgasm. I don’t forget the winter when I brush their petals off my shirt as I walk past. I remember the long dormancy of the apple trees, how long they’ve waited to become and how much they’ve endured in that waiting. The bitter frosts, grey mornings, a quiet desperation in their roots.

My surgery, the flowering trees, being loved in good and bad ways, waiting for bruises to fade into nothing, scars along the innermost part of me—these are my stories. They fill my body and animate my life. I am not an inspiration nor a monster. I am just a girl with apple tree petals in her hair, sneezing at their fragrant pollen as she walks to work.

I light a cigarette in front of the trees and hide in the shelter of their branches. Smoke trails out around me, illuminating the borders of sunlight, my body, and the invisible currents of wind. I imagine myself five months earlier. I see myself standing in the pre-dawn light of Laval as snow falls around me. I open my eyes to where I am now. I’m still in both places, the here and the past.

The new body, the old body. Laval, Toronto. Winter, Spring. Pre-operation, post-operation. Penis, vagina. In both moments, in every moment, I’m a woman.

If you take one thought away from my story, let it be that one.