Imagine if we could put Niccolo Machiavelli in a time machine and transport him to the United States on the eve of the November election. Could the author of that notorious how-to manual for despots, The Prince, even begin to comprehend how millions of Americans became vested with the power to choose their own leaders, much less provide us insight into our modern electoral politics? Well, the short answer is, far from being stupefied by a world in which one man rule has given way to the principle of one man, one vote, time-traveling Machiavelli would consider himself a vindicated prophet.

That’s because The Prince represents only a selective sliver of Machiavelli’s political thought. Machiavelli’s magnum opus is a much longer work, Discourses on First Decade of Titus Livy, in which he lays out his preferred form of government, a republic remarkably like the one established by the Constitution of the United States in 1787 (almost three centuries after Machiavelli’s death). Not only were America’s founding fathers familiar with The Prince and the Discourses (Thomas Jefferson’s personal library included both), they also shared with Machiavelli a profound admiration for the ancient Roman republic that endured from roughly 500 B.C. to 27 B.C.

Although Machiavelli had some practical experience with republics, having served as an ardently patriotic diplomat and envoy for the short-lived Republic of Florence, his political theory was shaped by his life-long study of Titus Livy, the Roman historian who began chronicling the Roman republic during the reign of Augustus, the emperor who ended it. Relying on Livy and his own observation of contemporary princes (a number of whom he personally knew), Machiavelli pragmatically concluded that “governments by the people are better than those by princes.” The multitude might err in judgment or be duped from time to time, but Machiavelli believed that over the long span of history, the people had proven themselves demonstrably wiser and steadier than top-down autocrats.

Just as important to Machiavelli was the meritocratic nature of republics. Again looking at the historical record, he observed that “republics cherished able men and princes destroyed them, since the first profited from the abilities of men, the second feared them.” But for this sort of meritocracy to work, Machiavelli believed a republic must carefully maintain a balance between the interests of the wealthiest citizens and ordinary working people; what today we call “class warfare” was an abiding concern for Machiavelli both as an historian and a public official. And if we had that time machine, Machiavelli’s views on class warfare would thrust him directly into the center of an American election where the concerns of the wealthy and the working middle class have never been in such stark opposition—nor so fully embodied by the two candidates for President of the United States.

In this match-up of political philosophies, it’s clear that Machiavelli would regard Republican candidate Mitt Romney’s trickle-down policies with great skepticism. Rather than granting unlimited license to the wealthiest in the belief that satisfying their ambitions will benefit everyone, Machiavelli saw those ambitions as the principal internal threat to a thriving republic. “To a great extent the ambition of the rich if by various means and in various ways a city does not crush it, is what quickly brings her to ruin,” opines Machiavelli in the Discourses, a judgment sufficiently harsh that it’s fair to suggest Machiavelli would have favored confiscatory tax rates for the wealthy and a broad leveling of incomes.

However, Machiavelli believed that absolute economic equality was both unattainable and undesirable; he simply felt that an increasing concentration of wealth at the top would lead to the political disenfranchisement of those at the bottom, which he regarded as more likely to lead to dangerous instability than economic disparity alone. Writing about a fourteenth century workers’ revolt in his History of Florence, Machiavelli noted that only when wealthy merchants and manufacturers “took over the entire government of city” were the underpaid wage-earners finally stirred to a violent and successful uprising. With this example in mind, Machiavelli would warn today’s Republican party that the combination of economic inequality along with efforts to amplify the political influence of the top earners (such as with the new billionaire-funded “super-PACs”) and disenfranchise the poor (such as the current spate of controversial voter ID laws) not only gravely weakens the long term health of a republic, but soon enough will rouse even a long-passive opposition to unexpected passion.

But if Machiavelli would favor Barack Obama’s less top-heavy political philosophy over Romney’s strategy of further empowering the most powerful, he would cite the president for extremely poor political tactics. To begin with, Machiavelli believed it best to downplay expectations when assuming office: “It is not a desirable thing to undertake either a magistracy or a princedom with an extraordinary reputation, because, since it is not possible to measure up to it with actions—for men desire more than they can get—at last it brings you dishonor and disgrace.” That’s why Machiavelli would almost certainly have noted the political danger presented by Obama’s “hope and change” agenda long before pundits and political foes began complaining about his failure to achieve it.

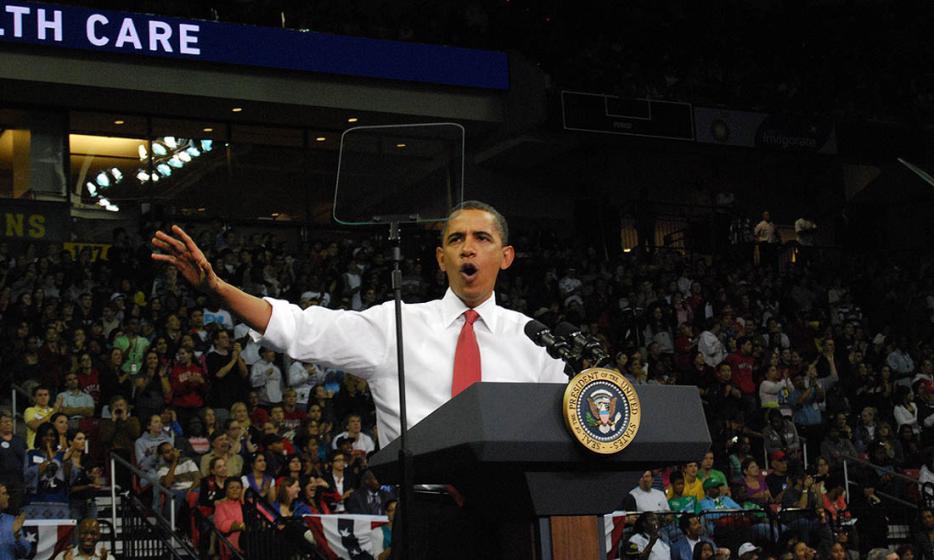

In his major policy initiative, health care reform, Obama violated one of my favorite Machiavellian admonitions: “Risking all one’s fortune without using all one’s forces is an injudicious strategy.” Obama learned nothing from the failure of his predecessor, George W. Bush, to support his bet-it-all military adventure in Iraq with a full commitment of U.S. resources, including calling for sacrifice at home. Obama’s adventure was legislative but no less ambitious than Bush’s, yet he similarly took a hand’s-off approach to management and soon found the opposition commanding the debate. Bush bet his presidency on an Iraq policy to which he did not commit the full force of the nation, and although he won a second term, it was disastrous for his reputation, his party, and the nation. Obama staked his fate on legislation he refused to defend or even explain with the full force of his office, and he may lose his presidency—as well as see its signature achievement wiped away—for that failure to commit.

So how would Machiavelli rate the Romney-Obama race? He was a voracious information-gatherer, always querying contacts and keeping his ear to the ground for news, so he would pay careful attention to polls that still see a toss-up. And in a race too close to call, he’d probably suggest that his old nemesis, Fortune, that goddess of random events, will eventually direct her malice at one candidate or the other and tip the balance. Regardless of who wins, however, Machiavelli would tell us that either Romney’s flawed politics or Obama’s poor tactics are likely to make the American people the losers.