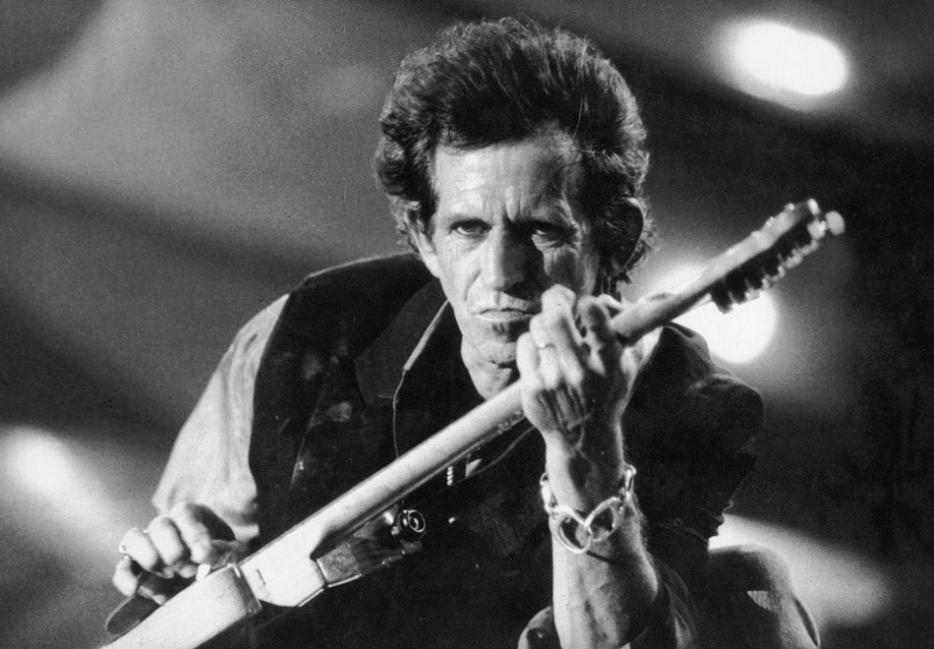

When Keith Richards snorted his father’s ashes off his dining room table in 2007, it wasn’t an act of ritual so much as an act of housekeeping. “I pulled the lid off [my father’s urn] and out comes a bit of dad on the dining room table,” Richards told the New Musical Express later that year. “I’m going, ‘I can’t use the brush and dustpan for this.’” Originally, Richards claimed to have cut the ashes with cocaine, but later said that he took his father straight. “My dad wouldn't have cared,” Richards said. “He didn't give a shit.”

In There Goes Gravity, Lisa Robinson’s new book about her years following bands like the Rolling Stones, Led Zeppellin, and the Clash, parents occasionally loom up the way they do in Peanuts—indistinct shapes that might be legs with a suggestion of sensible adult shoes. The music column Robinson wrote in the NME mattered, she said, because “the New Musical Express was read by all the English musicians and, more importantly, because their children were musicians, their parents. The bands, Zeppelin especially, wanted their families to know they were big in America.”

To all appearances, Bert Richards didn’t give a shit about his son for about 20 years—between 1962, when Keith stormed out of the house and went off to live with his art school friends, and 1982, when Keith’s girlfriend Patti convinced him to give his father a call. After that, Keith and Bert became fast friends—Bert moved in with Keith’s ex, Anita Pallenberg, and their son Marlon. Bert and Keith drank together, ate bangers and mash, and played checkers until Bert found his sweet hereafter up his son’s nose. As parent-child relationships go, it’s a reasonable success story.

The problem with parents, generally speaking, is that they want you to be happy. Being happy is incredibly hard to do, and knowing this, parents tend to try for the next best thing: making you normal. The more you make it as a rock star, the less normal you are likely to be. The mums and dads of rock stars face, shall we say, unusual parenting challenges. Is it any wonder they often fail?

Shitty parents abound in the biographies of artists—some see an early lack of love and stability as contributing factors in creative development. But as Andrew Solomon writes in Far From the Tree: Parents, Children, and the Search for Identity, his exploration of how factors like autism, deafness, or schizophrenia affect the parent-child relationship, exceptional talent can drive a wedge between parents and children as easily as any other marked difference. Solomon writes: “Being gifted and being disabled are surprisingly similar: isolating, mystifying, petrifying...Like parents of children who are severely challenged, parents of exceptionally talented children are custodians of children beyond their comprehension.”

The problem with parents, generally speaking, is that they want you to be happy. Being happy is incredibly hard to do, and knowing this, parents tend to try for the next best thing: making you normal.

In his chapter on musical prodigies, Solomon focusses on classical musicians, who fit the stereotype of “gifted” children. “At eleven months,” Solomon writes of a Russian piano prodigy, “Zhenya sat down at the piano and with one finger picked out some of the tunes he had been singing. The next day he did the same, and on the third day he played with both hands, using all his fingers.” In a biography of Keith Richards, Victor Bockris writes, “According to his mother, Keith sang with her to the radio and from the age of two had perfect pitch. Soon he was correcting her if she wandered sharp or flat.” Zhenya’s parents are musical themselves, but even they find his virtuosity unsettling: “As it went on, relentless, nonstop,” his mother, Emilia, recalls, “I became frightened by it.”

Bert Richards was more angry than scared; when Keith would practice guitar for hours standing at the top of the stairs or in the bathroom for the acoustics, Bert would tell him to stop that bloody noise.

Rock stars want their parents to love them and approve of them, just like everybody else.

That man onstage baring his chest in the company of a giant inflatable cock is also somebody’s baby. But unlike classical musicians, rock icons have a second duty: to embody the teenage rebellion we all need so desperately. Like the world of Peanuts, the world of rock music is supposed to be an adult-free zone—when you’re a teenager, having your parents ask about what music you like is as squirmily embarrassing as having them ask about your sex life. I’m not so sure I want rock stars’ parents to be proud of them.