The life of a concert promoter is tough—it isn’t easy like some people think. Like most music industry jobs, it sounds lofty and vaguely unreal, like “record producer” or “band manager” or the label executives you see on TV. But putting on shows—a needlessly complicated process involving paperwork and booking agencies and riders, background machinations nobody ever sees—is real, actual work, more labor-intensive in its own way than touring in a band, less stable an entrepreneurial endeavor than running a brick-and-mortar business, and rarely as lucrative as working for minimum wage. What it isn’t is thankless: people are happy to see their favorite artists perform in their city and they will gladly commend you for making it happen, usually before asking to be put on the guestlist or complaining that the set times are too late. The musicians, too, will shake your hand, though usually while wondering aloud why the green room is only stocked with four bottles of Jim Beam instead of the five stipulated in their contract.

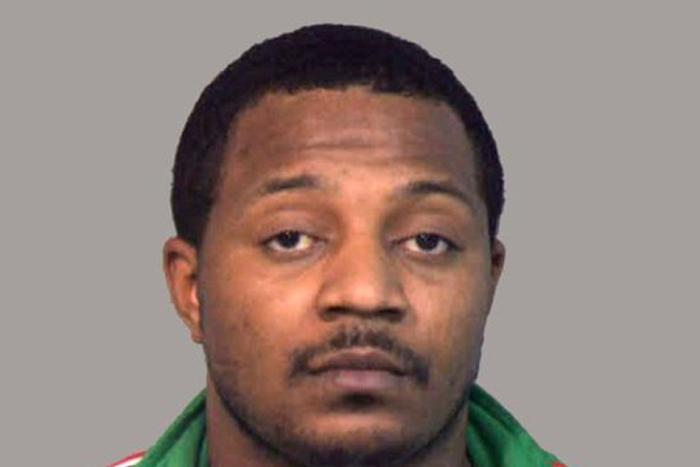

With the exception of Peter Fonda’s antagonist in The Limey and an Ice Cube comedy called, ahem, The Janky Promoters, concert promotion is a profession very rarely depicted in the cinema. I have, however, always held that the strain of those pre-showtime moments, that feeling of suffocation from the stress of not knowing, would make for a tense bit of drama. Michelle Latimer’s Alias, which has its premiere during this year’s Hot Docs film festival, proves that the plight of the promoter does indeed lend itself well to on-screen dramatics, and it does so without recourse to fiction. The film follows the independent hip-hop scene in Toronto, looking at the daily grind of three hard-working rappers as they struggle to break into an unforgiving industry. On the periphery of the story is Knia, a promoter and self-styled businessman trying to give the scene some semblance of shape and order; Alias finds him schlepping around town, penciling artists into timeslots on an ever-expanding spreadsheet, making follow up calls with the bluetooth headset that never leaves his ear. The film makes a point of showing how hard it is for local rappers to turn their passion into a career, but for me the major player was this well-meaning guy trying to give his friends a shot on stage, pouring his savings into projects that never seem to pan out.

I became a concert promoter, and remained one full-time for roughly five years, for what I imagine is the same reason most misguided music fans do: because it seemed cool. And, to be fair, the vocation does indeed carry an air of justified glamor, felt at its height in the middle of a sold-out show, when you can glide through the crowd with the sense that they are there enjoying themselves, in essence, because of you and your efforts to bring them there. If live music is the experience, the promoter is what facilitates it: they’re a bit like a movie producer, bringing together the talent and funding their work together, maintaining a schedule and budget and ensuring it all runs smoothly. And much like producing a film, promoting a concert is by nature self-effacing. The best proof that a concert was well-promoted was if you didn’t notice anything wrong with it. Did the band start an hour late? Was the venue overcrowded? Had the soundcheck been so delayed that none of the equipment was properly tested, which nobody realized until the band went to break into their opening song and found that their microphones weren’t connected? If the answer to these questions is “no” or in the very least “not as far as I could tell,” the promoter did a good job.

In Alias, after watching Knia nail down the final details of his latest business endeavor—a massive showcase of local rappers at Toronto’s Opera House, an 850-person hall usually reserved for national touring acts—we find ourselves at the club on the big night, hovering around a barely together Knia as he’s barraged with problems and complaints. It’s the quintessential promoting disaster: anything that can go wrong does, including a near absence of paying attendees. When he arrives on scene he’s told without warning that the two cops he’s been required to rent for the evening will have to be upped to six, which adds a further $1,300 to his expenses (a problem exclusive to rap gigs, unfortunately); as someone is thoroughly searched and patted down upon entering they complain, not unreasonably, that “this is worse than airport.” Knia quickly learns that his bill is over-booked, with those at the top not wanting to go on so early and those at the back scrambling to ensure they’re not left out. Rappers on stage look around in frustration at an empty room (“it’s all emcees”, says one, “where’s the fucking crowd?”). Nobody will get off stage when they’re supposed to. Someone offers advice: “You gotta tell people to be here at 6 if you want ‘em to be here by 9 or 10. You know how rap shows are.”

Most shows—or at least most ticketed events not big enough to be handled by a major corporation like Live Nation—involve three basic steps: booking, advertising, and orchestrating. How this typically works is that a promoter will contact a booking agent about a particular band or artist, agree upon a tentative date, contact an appropriate venue to reserve that date, negotiate a fee for the performance, confirm the details and sign a contract to that effect, and spend every day until the performance putting up posters, distributing press releases, and, I imagine more regularly now than in my day, harassing prospective attendees over social media. None of these tasks are especially difficult on their own, but as a system of interrelated jobs—and on a scale of a few shows every week—the work involved is exhausting, and it can quickly come to seem unmanageable.

The really taxing dimension of the job isn’t the workload—it’s the pressure. Working as a concert promoter is stressful in a way that’s hard to articulate. Consider a hypothetical example: it’s May 1st and you’ve just booked a gig for up-and-coming indie rockers Band X through their agent, with whom you’ve agreed to the date of June 15th and a guarantee of $3,000. A “guarantee,” in the promoting world, is a fee that you’ve agreed to give an artist regardless of attendance or ticket sales; this is a bill that, no matter what happens on the night of the show, you are contractually obligated to pay at the end of show, in addition to the investment of advertising costs, venue rental fees, drink tickets, security, sound and light technicians, and meals for the artist—all of which, depending on the size and calibre of the venue, might double your expenses. Let’s suppose that in the first week of June, Pitchfork raves about Band X’s new album, or that a few days before the gig they perform on Letterman; your venue sells out its capacity of 500 people before the doors are open and, at $15 per ticket, you’re set to make a cool profit. But let’s suppose that in the first week of June, Pitchfork slams Band X’s new album. Suppose that, though you didn’t know it on May 1st, June 15th happens to also be the night of a major local sports event, or a bad thunderstorm, or a more important concert. Whatever the reason, if nobody shows up, the promoter is left with the bill.

Unless they are exceptionally lucky or can somehow predict the future, every concert promoter will face those dismal latter nights. The experience can seem unbearable. Losing money isn’t the worst of it, either: it’s the tension of not knowing until it happens that bears down on you, weighing on every thought, forcing you to keep a hard eye on the entrance. If June 15th rolls around and you’ve only sold a few dozen tickets, things can still go one of two ways: people either show up or they don’t. I’ve promoted shows at which I did eventually break even—I sold hardly any tickets in advance but found a big enough crowd turning up around midnight—but spent so much of the evening worrying whether anybody would turn up that, in terms of the psychic toll, it would have been the same for me in the end if they hadn’t. You find yourself milling about backstage at 10:30, peering out at a half-empty room, watching the door in desperation like some schlub being stood up for a date. It is a truly miserable feeling.

That, of course, is how every show is. What Alias captures, maybe even accidentally, is a very universal sort of frustration, one that will be immediately recognizable to concert promoters everywhere. Nobody likes to see an empty room; even now, years later, I feel stressed out on behalf of strangers when I attend a show and see that it’s sparsely attended. By the end of the evening Knia is paying the cops with the last of his spare cash, offering to pay one his final $25 by cheque. “I lost two g’s tonight,” he bemoans. “That’s my daughter’s OSAP money.” The thing is, that’s more common than most people realize—it’s a risk inherent to every live music event, of which there are a half-dozen every night in this city alone. It’s one person’s invisible dice roll keeping an audience entertained from behind the scenes, and I doubt the stress is worth the happiness it brings. Or the appreciation: Knia is hounded at the end of the night by friends who were never able to perform as a result of rescheduling, including Alcatraz, who complains of having hired a babysitter for nothing. Knia failed even after trying his best. You have to admire the guy even after you feel sorry for his losses—the job begins to look less like charity than outright self-abnegation. I doubt if it was the intention, but one of the best things about Alias is that it operates as a kind of self-explanatory cautionary tale: if you watch it you’ll never think about putting on a concert again.