Stephen Reid and Li’l Wayne are just two members of an ancient fraternity of writers who have done some of their most notable work behind bars. Miguel Cervantes famously described how parts of Don Quixote were penned while he was locked away in debtor’s prison. And I’ve read that the only time the pervy and wordy Marquis de Sade was ever able to get anything on paper was when he was locked away—serving time on indecency charges. Two giants of Russian literature, Dostoevsky and Solzhenitsyn, took their harrowing experiences of incarceration and transformed them into art. But the genre of the prison novel, or memoir, goes deeper and farther afield than one might initially think. Hazlitt picks ten accounts of time both served and stolen, by people who understood what it means to live in the absence of freedom.

The Man Died: Prison Notes (1972)

Wole Soyinka

Shortly before he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1986, Wole Soyinka’s memoir of his prison time (for appealing publicly for a ceasefire during Nigeria’s civil war) was banned in his home country. Because he was not permitted writing paper, The Man Died was scribbled, along with several poems and plays, between the lines of other books while he was held in custody.

“Cages. Cages of concrete and a mere wicker-gate of corrugated iron for passage. A stolid form guards such loopholes and the gate itself is a barrier of heavy bolts, unspeakable padlocks. A hand is inserted through a hole in the gate, an eye peeps through, a key is turned and a bolt drawn. We pass through. Again journey’s end not yet in sight. A disembodied hand wrestles free bolts that thunder in each yard of echoes, always that square-cut hole in the gate, a torturer’s hand and the gate opening inwards, pulled to hide the face and body of the door-keeper. Are you afraid of me? Or ashamed, that you cover yourself with a shield?”

Kolyma Tales (1978)

Varlam Shalamov

Varlam Shalamov wrote Kolyma Tales over a span of twenty years, the stories based on his experience of Soviet labour camps on and off for seventeen years. His first arrest came as a student in Moscow in 1929 for attempting to publish Lenin’s Testament. Later, in 1943, Shalamov would be sentenced to ten more years in the camps for the crime of describing Ivan Bunin as a great Russian writer. Bunin, in 1933, had been the first Russian writer to win the Nobel Prize for Literature.

“We were disciplined and obedient to our superiors. We understood that truth and falsehood were sisters and that there were thousands of truths in the world…We considered ourselves virtual saints, since we had redeemed all our sins by our years in camp. We had learned to understand people, to foresee their actions and fathom them. We had learned—and this was the most important thing—that our knowledge of people did not provide us with anything useful in life.”

Soul on Ice (1968)

Eldridge Cleaver

Incarcerated for rape and assault in 1958, Cleaver wrote many of the essays collected in Soul on Ice before he was released in 1966. After leaving prison, Cleaver joined the Black Panthers. The book was published in 1968, coinciding with Cleaver’s bid to become president of the United States of America.

“I was twenty-two when I came to prison and of course I have changed tremendously over the years. But I always had a strong sense of myself and in the last few years I felt I was losing my identity. There was a deadness in my body that eluded me, as though I could not exactly locate its site. I would be aware of this numbness, this feeling of atrophy, and it haunted the back of my mind.”

Memoirs from the Women’s Prison (1986)

Nawal El Saadawi

Charged by President Anwar Sadat with “crimes against the state” in 1980, Egyptian feminist activist Nawal El Saadawi was only released from prison after his assassination in 1981. She then went on to form Egypt’s first legally recognized independent feminist organization, the Arab Women’s Solidarity Association. The AWSA was later disbanded by the government, for criticizing American involvement in the Gulf War.

“In prison I came to know both extremes together. I experienced the height of grief and joy, the peaks of pain and pleasure, the greatest beauty and the most intense ugliness. At certain moments I imagined that I was living a new love story. In prison I found my heart opened to love—how I don’t know—as if I were back in early adolescence. In prison, I remembered the way I had burst out laughing when a child, while the taste of tears from the harshest and hardest days of my life returned to my mouth.”

On the Yard (1967)

Malcolm Braly

Kurt Vonnegut called On the Yard, “Surely the great American prison novel” and Jonathan Lethem, “the novel prison needs.” Malcolm Braly spent over 20 years in various prisons, convicted of burglary. His memoir, False Starts, describes his turn to crime: “At a certain age most boys steal. Most also stop. I didn’t.”

“Transporting convicted prisoners, now literally convicts, to the state prison is the responsibility of the sheriff, and the county had converted an old school bus into a prison van. Welded bars over the windows enclosed the driver in a separate cab, and the original orange-and-black had been repainted gray. Manning had occasionally noticed this van. It had seemed to move in a cloud, not of disgrace, or danger, but enveloped by a separate atmosphere. A stout gray bird of passage coming from one alien land, bound for another.”

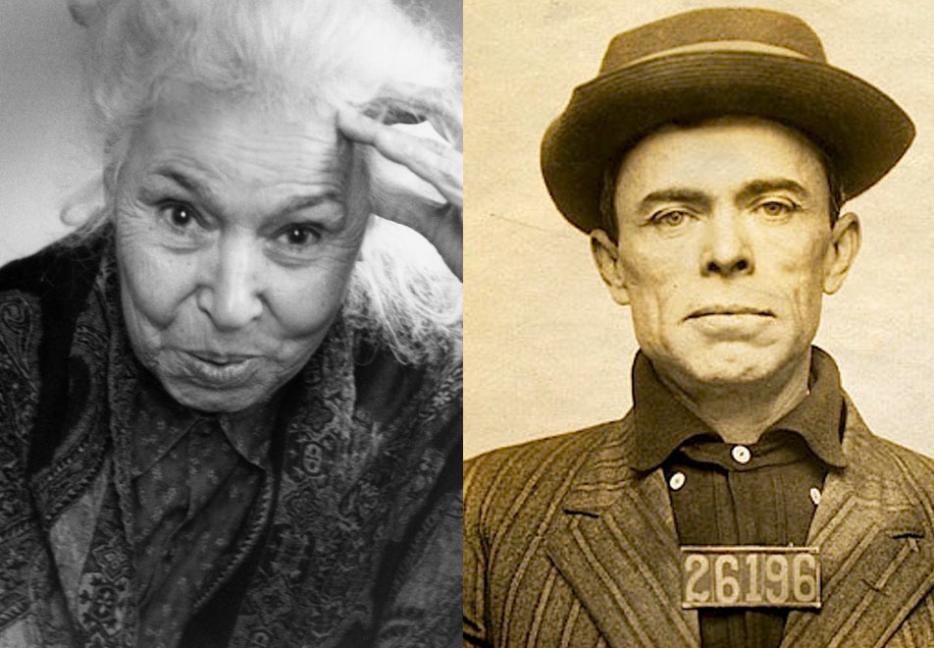

You Can’t Win (1926)

Jack Black

Jack Black’s autobiography of a freight-hopping thief in the early 1920s debuted as a best seller. He details the time he’d spent inside various jails and prisons, and in a few instances, how he escaped. The book was enormously influential on William S. Burroughs, who wrote in the introduction to a later edition that Black’s “code of conduct made more sense to me than the arbitrary, hypocritical rules that were taken for granted as being ‘right’ by my peers.”

“To say I was shocked, stunned, or humiliated on entering the penitentiary would not be the truth. It would not be true in nine cases out of any ten. It would be true if a man were picked up on the street and taken directly to a penitentiary, but that isn’t done. He is first thrown into a dirty, lousy, foul-smelling cell in some city prison, sometimes with an awful beating in the bargain, and after two or three days of that nothing in the world can shock, stun, or humiliate him. He is actually happy to get removed to a county jail where he can perhaps get rid of the vermin and wash his body. By the time he is tried, convicted, and sentenced, he has learned from other prisoners just what the penitentiary is like and just what to do and what to expect. You start doing time the minute the handcuffs are on your wrists. The first day you are locked up is the hardest, and the last day is the easiest. There comes a feeling of helplessness when the prison gates swallow you up - cut you off from the sunshine and flowers out in the world - but that feeling soon wears away if you have guts. Some men despair. I am sure I did not.”

Almost Home (2005)

Damien Echols

Self-published while Damien Echols was still in prison, Almost Home describes Echols’s life on death row. Echols, along with two of his friends, was famously convicted of the murder of three boys in West Memphis in 1993, though the verdict was overturned in 2011. New DNA evidence undermined the prosecution’s case, and Echols was partially exonerated, sentenced only to time served for a crime he says he did not commit.

“The thing about the prison administration is that they will abuse you as long as you’re quiet. The only way they can’t hurt you is if someone is paying attention. I started talking to more people, doing more interviews, because I knew only that would make them leave me alone. They can’t afford to harm you if the world is watching. They could not drag me into a dark alley, if I had a spotlight shining on me.”

Prison Memoirs of an Anarchist (1912)

Alexander Berkman

A leader of the anarchist movement in the early 20th century, the Russian-born Berkman was imprisoned for 14 years after attempting to assassinate the industrialist Henry Clay Frick in 1892—the killing, it was hoped, would instigate a mass uprising. Berkman was a longtime friend and occasional lover to fellow anarchist Emma Goldman, and she was the only person to keep correspondence with him while he was incarcerated. She figures in his memoir as “the Girl.”

“The melancholy figures line the doors as I walk up and down the hall. The blanched faces peer wistfully through the bars, or lean dejectedly against the wall, a vacant stare in the dim eyes. Each calls to midg the stories of misery and distress, the scenes of brutality and torture I witness in the prison house. Like ghastly nightmares, the shadows pass before me.”

This Blinding Absence of Light (2001)

Tahar Ben Jelloun

Based on the actual testimony of a political prisoner held in a Moroccan secret prison under King Hassan II from 1973 until 1991, Jelloun’s IMPAC-winning novel describes in stripped-down prose the torture of inmates held in dark underground cells for almost two decades.

“How many times did I convince myself that the earth was going to gape open and swallow me! Everything had been quite well planned. For instance, we were allowed five quarts of water a day. Who had specified this amount? Doctors, probably. Anyway, the water was not really drinkabl. I would pour some into a plastic jug I had and let it sit for a whole day. At the bottom of the jug would be a deposit of silt and slimy filth.

Since they had provided for everything, perhaps they had laid the flooring in the cell so that it would tilt after a few months or years and hurl us into the mass grave already dug right under the building.”

Everyman Dies Alone (1947)

Hans Fallada

Fallada was detained both in prisons and sanatoriums under the Nazi regime. Having already won acclaim as a novelist, Joseph Goebbels ordered Fallada to write anti-Semitic novels as propaganda for the party. While in an insane asylum he was able to get writing paper by mentioning his assignment from Goebbels’, though in the end he actually wrote a scathing autobiographical account of life under the Nazis called The Drinker. Shortly after the war Fallada wrote Every Man Dies Alone, one of the first German novels to explicitly criticize Nazism. He based the book on the true story of Otto and Elise Hampel, a working class couple who became active members of the German Resistance, and were executed by the state. Fallada died a few weeks before its publication. (The most recent English publication of Every Man Dies Alone includes photographs of the couple’s postcard campaign against the Nazis.)

“I spent some time where you’ve just been. Yes, it’s true, things are better here. At least they don’t knock you about. The warders are usually dull, but not completely barbarous. But prison is prison, you know: that doesn’t change. I have a couple of privileges. I’m allowed to read, smoke, get my own meals delivered from outside, use my own clothes and bed linen. But I’m a special case, and even with privileges, prison remains prison. You need to get to a point where you no longer feel the walls.”