Here’s how Nick “The Tooth” Gullo, UFC photographer and professional superfan, lost the eponymous tooth. He doesn’t like talking about it—it’s really such a stupid story—but nearly everyone who cares about the UFC calls him The Tooth. So, everyone asks.

“You know those soapbox derbies?” Gullo asks me. He says he was helping some kids build the cars around two years ago. He was racing one, and they’re really fast, incredibly fast. By the fourth time he took a ride, the front wheel came off, he hit a curb and flipped. It didn’t knock his tooth out, but the root died, and it needed to be pulled. Then Dana White, President of the Ultimate Fighting Championship and an old buddy, started calling him The Tooth.

It’s a shame, then, that this is probably a bullshit story. See, Gullo has different versions of how his front tooth went missing. On this very Toronto press tour, he told Global that a surfing accident knocked it out. He told The MMA Digest that, on a bull-riding dare in Mexico, he was kicked off against a fence. When I ask him about it, he admits there are at least 10 iterations, including a slingshot fight with neighbourhood kids, and a weird tale that starts with him hiding in a casket at a funeral home to scare coffin-shoppers and ends with a woman accidentally kicking it over. (He swears that last one happened, but it isn’t the reason he lost the tooth.)

The only part of the story that doesn’t falter is that the great Dana White—the man who made the UFC the world’s largest mixed martial arts promotion company—started calling him The Tooth. White is how Gullo got into jiu-jistu; he also wrote the foreword for Gullo’s new book, Into the Cage: The Rise of UFC Nation, a collection of behind-the-scenes photographs of MMA fighters alongside a sweeping history of the sport, from the Gracie family, who brought it to North America, all the way to UFC’s brand new women’s league.

White grew MMA from obscure pastime to one of the most popular sports in North America. Before he took over the UFC in 2001, mixed martial arts fighting, which combines striking (punching, kicking) with grappling (wrestling, basically aggressive cuddling) was generally considered a form of human cockfighting. It was unregulated, underground, dangerous, and responsible for countless injuries: Serious fans still remember the 1998 fight between Douglas Dedge and Yevgeni Zolotarev, during which Dedge was mounted, took 15 punches to the head, and died two days later in the hospital from severe brain injuries.

The men who dared enter the Octagon in the ‘90s were either extremely brave or profoundly stupid. But White established rules for the game, enough to make it a legitimate sport in addition to a bloodbath. Crowds at live UFC fights erupt in roars or gasps when they see him walk to the Octagon, clad in a black dress shirt and crisp suit jacket, to watch his fighters. He shakes a few hands and sits right up close to the action, almost as big a spectacle as the fight underway before him.

He’s also hugely private: little is known about him other than he doesn’t seem to want to put up with anyone’s bullshit, particularly that of his own fighters. In fact, Gullo is one of a few rare public links to White’s previous life. The pair are old friends from their teenage years in Las Vegas, a kind of Pinky and the Brain, although physically their pairing is counterintuitive: Gullo stands a few inches taller than my 5’5 frame, slim but solid, with his hair standing on end. White is the approximate size of a truck, bordering on 6 feet tall, around 200 pounds, and bald. (The Tooth sometimes refers to him as “Gorilla” in the book.) While White runs the business, Gullo does unofficial PR for the sport, tweeting about it and basically letting UFC Lightweight Joe Lauzon clobber him in a promotional stunt.

If Dana White is the gruff king, Nick Gullo is the sensitive jester, happy to make an ass out of himself. “[Fighter Georges St. Pierre] is the archetype of the white night. Sir Lancelot,” Gullo says. “The Diaz brothers are the archetypal anti-heroes. I’m going to play up this idiot, this jester character.” There seem to be two versions of Gullo: the first is a serious author, a photographer, a family man, the guy who wears thick-rimmed glasses. The second version, who emerges when Gullo removes his glasses, is The Tooth: a fighter, a bro. He weaves between the two throughout our afternoon together.

*

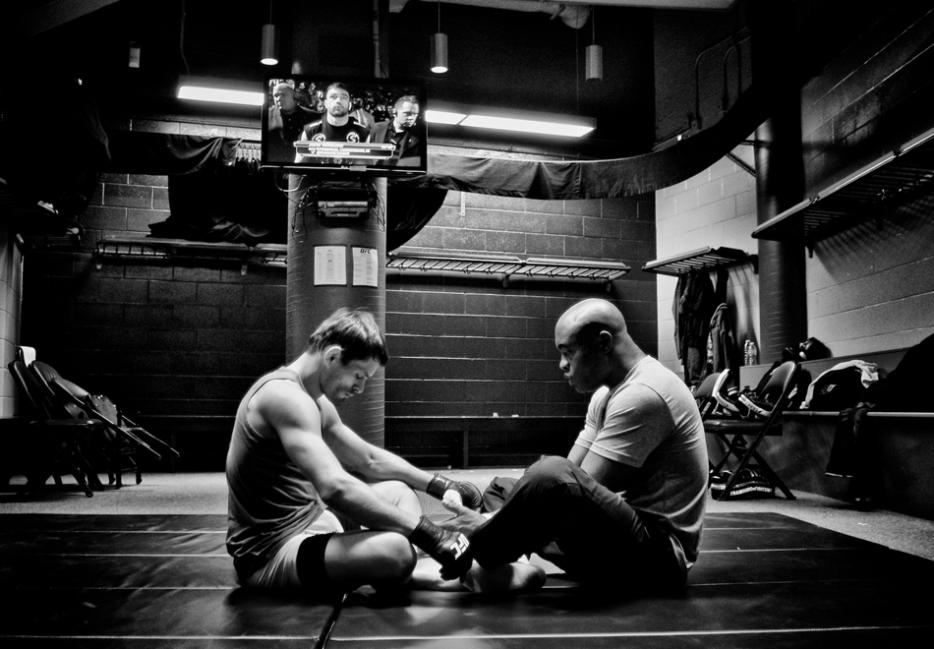

We meet at Toronto BJJ, a mixed martial arts academy in Toronto’s west end, where he bursts in proudly wearing the gap in his smile, shaking everyone’s hand, unable to stand still for a hot second. “I’m hungover,” he tells me, drawing the words out with an odd mix of California surfer dude and Southern drawl. He recounts how he went drinking on the Ossington strip the night before with some fighters he met at his book signing. Other than the bags under his eyes, there’s no indication that he’s tired or slow, which is a shame, because I’m about to have my ass handed to me.

Dana White’s best friend is going to show me how to grapple.

He wants to be a certain kind of writer: the kind who writes about the human condition. The kind who can peer into the reader’s soul. The kind of writer who does not live in New York. “Writing is supposed to illuminate life for us. You wonder why the literary crowd becomes so insular, because it’s all in New York,” he says. “They publish in New York, they write in New York, they read in New York. It’s such a crock of shit!” Perhaps remembering that his publisher is also based in New York, Gullo gets a little bashful. “Don’t make me go on a soapbox about literature.”

Soon, I lose him again, and he starts talking about Andy Kaufman. “Andy Kaufman was there to fuck with your expectations. Half the time, he wasn’t even funny and people hated it,” he says. “I love that.”

*

It’s unclear how much of Gullo’s routine—the goofy way he ends his sentences with “man” or “bro,” the way he will suddenly stop talking, slink back in his chair and completely detach from conversation—is actually a farce. When Gullo goes to the bathroom during our lunch, he returns with soaking wet hair, entirely unexplained. He teases Hazlitt’s podcast producer for being bald, laughing from deep in his gut. He says he cuts his own hair because “you watch something enough times, you friggin’ learn it.” Every morning, he drinks “Gorilla Coffee,” an ungodly combination of coffee, almond butter, coconut oil, and Stevia. He says he’s a vegetarian because he’s grossed out by all the “blood and guts” in meat, seemingly forgetting what the UFC is all about.

He also loses himself in a tangent about quantum physics.

Before we finish our desserts, Gullo leans toward me. “Feel this,” he says, gesturing to his right ear. I squeeze the skin and cartilage between my fingers. The top of his ear is solid, with no give or elasticity—years of fighting have given him a cauliflowered ear. Gullo has some odd affection for all the things wrong with him. “We love people for their imperfections,” he says. “I don’t want to hear about how perfect you are. You can’t take yourself so goddamn seriously.”

Top image via Into the Cage

Author photo via Elliot Raymond