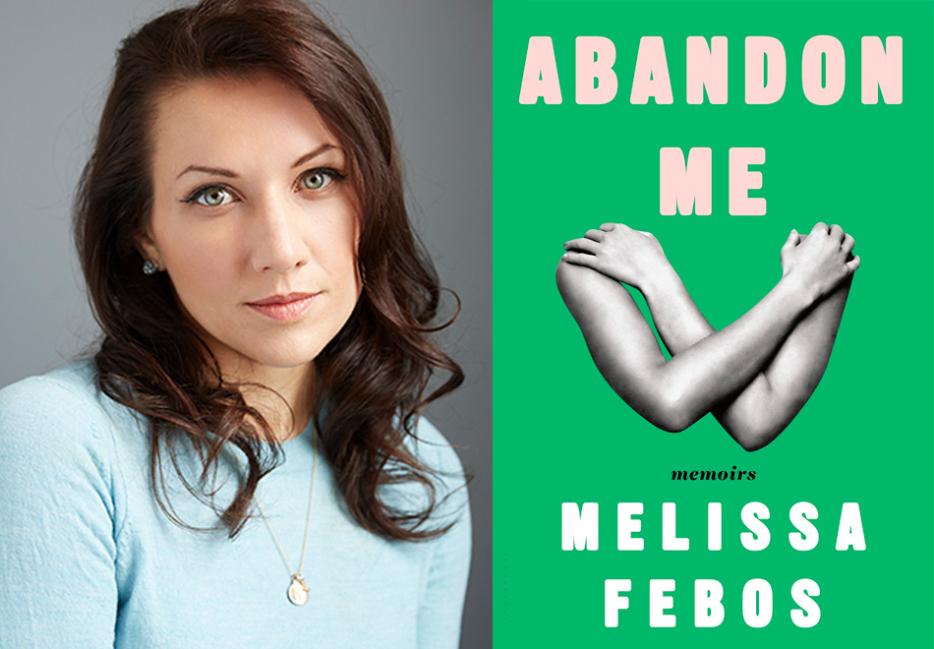

Melissa Febos’s debut memoir, Whip Smart (St. Martin's Griffin), chronicled her double life as a successful university student and heroin-addicted dominatrix. Nuanced and highly perceptive, it’s a queer, feminist book on BDSM. Peel back the layers of the seven interconnected essays in her latest work of non-fiction, Abandon Me (Bloomsbury), and you’ll find many of the thematic concerns that compelled Febos in her first book: reconciling multiple identities, exploring the complexities and contradictions of human sexuality and romantic love, recognizing the continuity and connection between our bodily and intellectual selves.

While the primary plot of Abandon Me follows the author’s obsessive love affair with a married woman, Febos also gets intertextual with Winnicott and Freud, meditates on her brother’s bipolar disorder diagnosis, and mounts an enthusiastic defense of hickeys. Abandon Me is also a tale of two fathers: one, her adoptive sea captain father, the other her birth father, whose re-emergence in her life as an adult connects her to her own Indigenous heritage. Febos’s latest memoir is a non-linear adventure in healing, a text that recognizes personal stories have the ability to influence collective memory, build worldviews and shape what we perceive as history.

Laura Clarke: One of the many things I loved about Abandon Me was how this fully realized queer universe exists without explanation or instruction to a straight audience. You discussed your sexuality openly in your last book, but by virtue of exploring a job that caters to the desires and gaze of predominantly straight men, it had a different texture and approach. Three quarters of the way into Abandon Me, you mention offhandedly that your mother is also bisexual. The text seems like an exercise in queer world-building to me, which is an inherently political act.

Melissa Febos: Thank you so much! That makes me feel really good. I mean, on one hand, it saddens me that taking my queer life for granted as something that doesn’t require explanation or need to be the subject of any story in which it exists is radical or political. I also recognize that it is. On the other hand, I am so happy that I’m able to embody that for myself and subsequently model it for my readers. I do take the queerness of myself and life for granted, in the sense that I don’t question it and I don’t feel a need to justify or explain it.

Representation of that perspective in my writing is an exercise (in a straight world, that is), but in my life it’s not, and that’s both a gift and a reward. It’s a reward for having spent a lot of time and energy building a life in which I’m surrounded by people who share and/or accept queerness, and a reward for building an acceptance and knowledge of self that feels very safe on the interior. It’s a gift in that it’s a result of having been raised by people who always accepted me as I am, and encouraged and reinforced my expression and acceptance of self. My mother gave me a lot of the tools that have helped me build this life for myself. It’s also a gift to live in a time where I have the resources and freedom to cultivate all of that.

In another interview, you describe Abandon Me as queer in both content and form. Can you expand on that?

In a sense, my creative process is similar to my living process. I enjoy a freedom on the page to be curious and explore my own ideas and questions and experience, to experiment with form and content without feeling overly constrained by convention or the expectations of other people or my culture. That wasn’t always so. As a younger writer, I felt more obligation to adhere to structures given to me—both in terms of narrative and poetics—and I needed to acquire a better familiarity with those structures and more confidence in my own instincts and the art I wanted to make, in order to subvert them. I could not have written this book a moment sooner than I did. I hope I get to say that about everything I ever write.

Whip Smart is primarily a book about understanding the desires of other people, and the confidence and sense of power that comes from that position. Abandon Me is the opposite in many ways: it’s about personal desire and the resulting vulnerability. There are so many more scenes of intimacy in Abandon Me (sexual, romantic, familial) than in Whip Smart, despite the fact that there are probably more sexual scenes in the latter. Did one book begin from a place of more certainty, direction, a clearer sense of narrative arc, or did they simply arrive at different destinations from a similar writing approach? Did writing while in the middle of your experiences as you did in Abandon Me have something to do with the sense of rawness and intimacy you conjured?

Yes to all. The best questions are sometimes embedded with their answers, as this one is. Whip Smart was a more shocking book, but far less intimate. Again, I think with both of these books, I was working at the limit of my ability—in terms of craft, confidence, and intimacy—and my capacity was so much greater with Abandon Me. It was an enormous task, with the first book, to be honest with myself about my own experiences and motivations. I don’t think I could have managed much aesthetic experimentation along with it. I was only twenty-six when I started it and still a graduate student. But I needed to write that book. Which is to say, I needed to understand what had happened and why. So much of finding our best work is finding the work that asks more of us than we have ever given, more even than we are capable of.

I wrote much of Abandon Me in the eye of the story, and you’re right that I could not have done that as a younger writer. At thirty-five, I had more tools, was able to experiment formally, and also to derive insight more quickly after “leaving” the story, in the second half of the book. I could enter into my own experiences more than I had been able to in Whip Smart, and so could bring the reader with me, however terrifying that might be (and it was). In the end, I think that for all its experimentation, the narrative arc of Abandon Me is pretty straightforward, but I didn’t know that at the outset. I believe that on some level I knew exactly how it would end, but I couldn’t bear to look at that truth before I arrived there in the work. And writing toward an end you cannot see—which is analogous to so much of living—requires a lot of faith.

Reoccurring images of the stars and the sea are woven into the seven essays in this collection, which you partially attribute to being the daughter of a sea captain raised in a port town. The imagery seemed like an interesting artistic mirror to the book’s many childhood development psychology references (Winnicott, Freud, Jung. etc.), demonstrating how the past and history is not static, but rather actively shaping our perceptions at all times. Did the retracing of childhood and the past turn up this imagery for you, or is it just a part of your universe, your writerly toolkit?

Both. When I was younger, I had this idea that the quality of a writer was contingent on her imaginative invention, or a limited concept of invention. My work changed a lot when I began to trust my own instincts, which so often led me back to the images and environments of my own becoming. I see my students suffer from this same belief in the paucity of their own symbols, too. They read other writers, are impressed by the achievement of books, and mistakenly think, oh, that was so successful, and in order to write a successful book it has to be like that. Sometimes, they think, well, I should just quit because I’ll never write that book, I’ll never be good enough. It’s a common logical fallacy for young, insecure artists. When I decided that I didn’t need to write like any favorite writer, or anyone but myself, I was so liberated. Ironically, I felt that my creative options multiplied.

I believe every individual’s life is rife with organic symbols. How could it not be? We wade through an infinity of images and symbols in a single day, and yet we remember only a miniscule number of these. In my late twenties, I began to think of every memory and image as symbolic, metaphorical in some way, and that immediately released me from the onerous pressure of finding or choosing the “right” ones. It reframed my work as a writer—rather than “inventing” my networks of images, which was at once a hubristic and impossible task, my job became that of uncovering or listening to the images that I already had. Perhaps this is especially relevant for the memoirist or personal essayist. When the subject of your work is your own life, why wouldn’t the images accumulated and made symbolic by that life be the most effective? In Abandon Me, so much of the book takes my early life for its subject, so this dynamic was further intensified. I actually had to go through the book in later revisions and prune out a lot of sea images because having yielded to those instincts yielded such a bounty that it was drowning out the story (see? I’m doing it even here!).

I think every writer reading this just breathed a sigh of relief for you validating our strange, reoccurring images. When you connect with a writer’s own index of specific, weird imagery, it’s an amazing feeling. My friend and I exchanged new poems recently, and though they were short, they both contained an image of socializing with spiders. I felt creatively connected to her and happy in my own weirdness!

I love that! And I think that’s a realization, a reorganization of value that every writer has to go through. We are all socialized in conformity, to believe that weird is bad. At one time (and sometimes still) our survival depended on our ability to not be weird. But weirdness and the specificity of our own unique selves is what makes for good writing. This is one of the myriad ways that writing has grown me as a person—it has taught me how to recognize, acknowledge, and ultimately value my own eccentricities. My girlfriend often stares at me in wonder and says, You’re so weird! You’re one of the weirdest people I’ve ever met, and it’s fully an endearment. I think good art has so much in common with good love: an ability to recognize and appreciate the unique specificities of an object, a person, a perspective.

You return to an image from Whip Smart in Abandon Me with a slightly different perspective—a woman is suspended in the air from meat hooks in her back at a fetish party. You describe how at the time, you attributed a fantasy of showing your younger self this vision as a desire to “annihilate her innocence.” But in this new imagining, you see your impulse as a tender one, something to do with catharsis and personal choice. What changed your perception of this memory? I love the idea of living texts, that in writing we can return again and again to certain images and memories and re-evaluate them.

Oh, I’m so glad that scene stood out for you! It was such an important one for me. I fought it for a while before I let it into the book. After writing Whip Smart, I had this idea that I had said so much about addiction and innocence and power dynamics and my experiences as a pro-domme that I wasn’t allowed to write about them again. I was sick of being the dominatrix writer, a label I’d never identified with and that frustrated me. That rigidity was also an expression of my own wish to be completely finished with it. But I wasn’t done, and maybe I’ll never be done, and also thank goodness. If our perceptions of our own lives and beliefs and interpretations weren’t allowed to evolve, where would we be? In many respects, I consider it a job of the writer (particularly the essayist and memoirist) to enact this evolution of perception for their readers.

My relationship to myself and my choices was so much more rigid, fearful, and punishing when I was younger. That’s what shame will do. It made sense to me when I was writing Whip Smart that this urge to expose myself to extremity was an impulse to shock myself, to teach myself to withstand anything as a defensive measure. In the intervening years, I came to understand that I was also looking for alternate solutions, for methods of healing and transformation outside of those taught me by my patriarchal, heteronormative culture. One of the many gifts of writing these books is the way they’ve taught me how to love myself, to step back and look with a gaze at once more generous and more brave than I was before.

I like what you said about methods of healing and transformation outside of patriarchal, heteronormative culture. There are a lot of “healing” narratives that are marketed to readers in easily digestible forms. The healing in your book is non-linear and individual, and it’s not always about following some traditional narrative arc from darkness to light. For some people, it might look something like hanging from meat hooks at the fetish party.

Right, and that’s both a fact and a priority of my work. Fact, in that the typical narrative arc, from darkness to light, has never worked for me. My narratives are more: light to darkness to darker darkness to darkest darkness to darkness as a kind of light. I think we get into a lot of trouble when we get attached to these binary ways of thinking about healing, transformation, and narrative. My happy ending is not about emerging from darkness into some perpetual light—that’s a religious greeting card, not a memoir. My happy ending is the discovery of a transformation that can happen in the dark. About figuring out how to be a light in the dark, or simply be in the dark, to love what is there and stop running from it. Carl Jung has a lot to say about darkness, and the shadow self, and I reread some of it while I was writing this book. He wrote that, “One does not become enlightened by imagining figures of light, but by making the darkness visible.”

We can miss our own chances for healing if we don’t look outside the models we are given for what healing should look like. It can happen in swimming pools with dolphins, in therapists’ offices, in dungeons, in love, under tattoo guns, in gyms, in any number of places. Our psyches are so much smarter than we give them credit for, and we are taught to overlook our own instincts in favor of a social or cultural wisdom that is more often based on commerce than compassion. I do think that the cultural wisdom about healing and transformation reflects patriarchal and heteronormative influences, but I don’t think it’s good for men or straight folks, either.

You begin researching the history of the Wampanoag tribe, and you meet with your literary agent, eager to write a book about the history of the violence of colonialism in the area. Your agent says readers “aren’t into Native Americans” and suggests you write something “more urban, more edgy...more you.” But you wrote all these things at once. And his very words are exactly what the book stakes its claim against – reducing anyone’s multiple identities into a singular consumable version, as well as erasure on a personal and historical level. Did the way this anecdote reflected on the greater work come to you later, or was it always on your mind while writing?

In some ways, that anecdote was unfair to my (then) agent. He was expressing the track record of a market that had been exposed to so few examples of integrative representations of marginalized experiences, and it wasn’t an incorrect expression. The publishing industry is not a creative one—it relies primarily on what has already been done and proven successful. And it is a reflection of the dominant narratives and power structures of our culture, and so overwhelmingly white, straight, and conventionally structured. In order to change that landscape, we have to write the things we have not yet seen on bestseller lists, we have to trust our own instincts and imaginations.

I can also see now that my impulse to write that book (which was an historical novel) was driven by my own desire to integrate all those seemingly disparate parts of my own identity. I was too scared to face it directly. I needed more time. In the years since, I have changed. And the publishing landscape has also begun to change in an important way. I don’t think an agent would say that, today. Or many wouldn’t. The brave writers who have trusted their instincts, their need to see their own stories represented in all their complexity and seeming contradiction, have created proof that there is a hunger for such stories, and so they are proliferating. Not, perhaps, at the rate that we’d like, but at a greater rate than we’ve seen in the past.

The expression of vulnerability in love we see in Abandon Me is important and refreshing to me, especially in a culture that places pressure on women to act chill and not “crazy.”

God, it didn’t feel refreshing when I was living it, but I’m so glad it felt refreshing to read. Vulnerability is the absolute worst! Of course, it’s also the best, but sometimes we have to trick ourselves into it, don’t we? Or sometimes our psyche has to go rogue and get us into a situation that we can only escape by becoming more vulnerable. I’m using a plural pronoun here, but obviously I’m talking about myself. I was so good at being chill and not crazy, for so long. Like, 32 years. And that imposed a pretty low ceiling on certain kinds of intimacy in love. Then, it was like I decided to get all my crazy vulnerability over with at once. Or make up for all those years of being chill in one short burst of agonized time. It really blew the doors off things, including my self-conception, and my belief that I couldn’t survive such a feeling of disempowerment. It did feel like I was dying, just as I had feared, but I didn’t die. And it felt important to tell that story, to demonstrate that resilience for readers who might relate to my fear and need for control, however limiting.

When I think of historical courtly love, the wooer/pursuer behaves as though they’re at the mercy of their beloved, when they arguably possess greater power. There’s a curious kind of power in a) fully abandoning yourself to the beloved and b) making art or a public record about it. Devotion can be an empowering act.

That’s such a smart observation about courtship and power dynamics in romantic love. Whip Smart was very much about looking at the superficial appearance of power dynamics in sex work, in commercial BDSM interactions, and between men and women, and then peeling them back to see how they so often reversed, and then sometimes reversed again. And I would say that much of Abandon Me conducts a similar examination of the power dynamics in a romantic relationship between two women. In consensual relationships, I doubt it’s ever simple. While one person often appears to have more power, that’s rarely as deep as it goes.

Were you thinking about these delicate balances of power when you wrote it, and did your perception of them shift during the act of writing, editing, publishing and so on?

In many ways, writing is my only effective thinking process. I do very poorly at thinking about things in my head. It’s only by writing, and to a lesser degree talking with other people, that I arrive at more nuanced understandings and new ideas about things. I suspect that the power dynamics of intimate relationships is a preoccupation of mine that I won’t be finished with anytime soon, and I’m fine with that. I’ve made peace with the fact that I am an obsessive person, and I’ll likely be chewing on these ideas for my whole life and career: power, sex, desire, gender, vulnerability, deviance, secrecy, and so forth.

In a review of The Argonauts by Maggie Nelson, you describe a sense of being granted permission through the act of reading. A reviewer in The Rumpus used the same language of permission when talking about your book. Does this sense of permission have something to do with the mingling of public and private, the bodily and the intellectual, of personal story and history? And isn’t it cool to think you are capable of giving that gift to your reader?

I do think it has something to do with that combination of things—with an expansiveness within the text, but also an expansiveness in…spirit? In intention? Maggie’s work is complex and rigorous and intimate, but I also feel invited into it, and I can sense her own curiosity and willingness to go where the process of inquiry takes her. There is room for her in the text, and room for me as a reader, bringing my own set of contexts and interpretations and biases. And it is that flexibility that gives me permission to interact with her content however I do. It’s an important reminder that I can move through my work as though it is an expansive space, and so it becomes one. My favorite texts (and maybe all kinds of art) share this quality. So, yes, it is the coolest ever that my work is being read the same way. I mean, it should be so, right? I aspire to create the sort of art that I love most, that has moved me most. Not necessarily in form or content, but in that intentionality, in the spirit of it, the geist.