The American frontier was a magical place. Daniel Boone wrestled bears in Kentucky and Davy Crockett battled a twelve-foot catfish in Tennessee. In Utah, grasshoppers grew so big they were barbecued like steaks, and in Arkansas, the corn grew so fast that a seed planted under a sleeping sow sprouted a stalk that speared the poor creature before sunrise. The frontier marked the outer limit of the ordinary. It was a “borderland of fable,” the historian Bernard DeVoto once wrote, an alternate reality where fact merged with fiction and a young, practical nation indulged its yearning for myth.

The frontier always lived vividly in people's minds. On the map, it was harder to place. In theory, it represented the line between wilderness and civilization. In practice, it was a porous, imprecise boundary between two different Americas: the populous East and the populating West—not one continuous front of white settlement but a patchwork of conquest and compromise spanning a vastly diverse region. The frontier improvised a society from many competing strands. Indians, northerners, southerners, blacks, Europeans, Chinese, and Mexicans overlapped and collided. Certain rules were suspended, others rewritten entirely. In these communities, America outgrew the colonial legacy of the Atlantic coast and created something new.

This evolution could be heard in the stories people told. In taverns and trading posts, stagecoaches and steamboats, they traded funny, fantastic yarns that reflected the new realities of western life. Tall talk was a kind of realism: a magnified portrait of actual speech, characters, and settings. It was also uncompromisingly coarse, the product of a male-dominated frontier. It broke all the rules of respectability, embracing vulgarity, violence, drunkenness, depravity, even ugliness. The heroes were hideous, and often hideously cruel. The language was exuberantly ungrammatical, composed in regional dialects that stretched and scrambled proper English into gorgeously expressive new forms.

These forms found their way into print via the nation's journalists. Reprinted from one newspaper to the next, popularized by periodicals in eastern cities, frontier humor became a national phenomenon, forming a “low” vernacular alternative to the high-cultural effusions of New England. Those “semi-barbarous citizens” described by Jefferson hadn't waited for their raw societies to become civilized before creating their own culture. They went ahead and did it anyway, using the materials at hand. The result wasn't just quirky spellings and quaint anecdotes. It was America's first folk art, a mortal threat to the literary dominion of the Atlantic coast. The revolt had been brewing for a while. On November 18, 1865, Mark Twain fired the first shot by publishing “Jim Smiley and His Jumping Frog” in the New York Saturday Press.

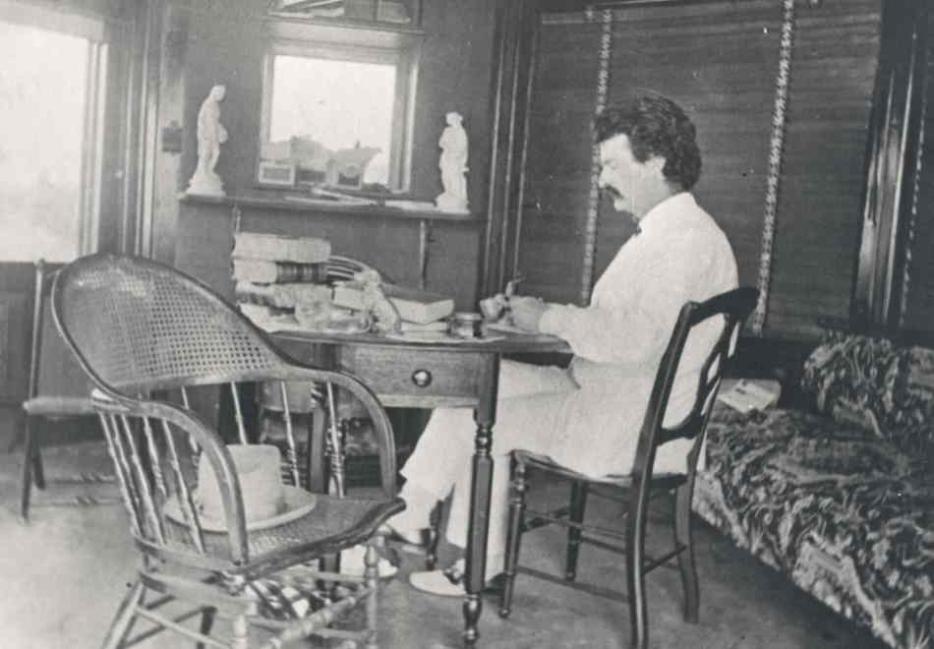

The path to publication had been anything but easy. Ever since returning to San Francisco from the Sierra foothills in February 1865, Twain had struggled to write the story he had heard at Angel's Camp about a jumping frog. He produced at least two incomplete drafts, trying to find the right tone, but he couldn't get this slice of frontier storytelling done to his satisfaction. He still hoped to send the piece to Artemus Ward in time for it to appear in his upcoming book. But time was running short: with each passing month, that opportunity receded.

What made the jumping frog such a difficult birth wasn’t just style or structure. The real problem involved a crisis of faith. Despite a prolific output and rising recognition, Twain had grave doubts about his future. Even as he developed a supremely confident writing voice, pummeling the San Francisco Police Department and other crooks and charlatans, he suffered serious misgivings about his chosen profession. As 1865 came to a close, the insecurities that he had long concealed under a swaggering exterior came painfully to the surface.

Money always made Twain crazy, even in those moments when he had enough of it. His father, John Marshall Clemens, had been a man of honesty, ambition, and appallingly bad business sense. He had started out as a lawyer, but it was his disastrous career as a speculator and entrepreneur that kept his family poor. The constant flutter of financial panic that Twain felt came partly from a fear of repeating his father’s failures. Wealth meant more than just fancy things—it promised a bulwark against chaos and uncertainty. Poverty, by contrast, represented something far worse than material scarcity: it brought shame and self-loathing. Throughout 1865, money problems kept Twain’s anxiety keyed to a constant pitch. He began sending daily letters to the Virginia City Territorial Enterprise in October, earning $100 a month. He made another $40 writing for the San Francisco Dramatic Chronicle. He still contributed to the Californian—although after the summer, his pace dropped to about once a month—and placed a couple of parodies in the San Francisco Youths’ Companion. In all, he earned the same income as he did as a reporter for the Morning Call, doing work he hated. But his wages couldn’t keep pace with his debts.

In Roughing It, his later narrative of these years, he would describe this as his “slinking” period. “I slunk from back street to back street to back street,” he wrote. “I slunk away from approaching faces that looked familiar.” It took a terrible emotional toll. “I felt meaner, and lowlier and more despicable than the worms,” he recalled. His former colleagues at the Call poked fun at his distress. “There is now, and has been for a long time past, camping about through town, a melancholy-looking Arab, known as Marque Twein,” the paper joked in October. This nomad wore ratty clothes, drank heavily, and changed lodgings whenever he reached “the end of his credit.” “Having become familiarly but painfully known to all the widows in town who let out rooms, he finds it expedient to move again.” A darker view was provided by Twain himself four decades later: driven to despair, he almost committed suicide. “I put the pistol to my head but wasn't man enough to pull the trigger,” he confessed. “Many times I have been sorry I did not succeed, but I was never ashamed of having tried.”

Unhappiness forced him inward. In November he would turn thirty. He was poor, unmarried, unsure of himself and his prospects. He grew reflective, philosophical. On October 19 and 20, 1865, he wrote a letter to his brother Orion and his sister-in-law Mollie:

I never had but two powerful ambitions in my life. One was to be a pilot, & the other a preacher of the gospel. I accomplished the one & failed in the other, because I could not supply myself with the necessary stock in trade—i.e. religion. I have given it up forever. I never had a "call" in that direction, anyhow, & my aspirations were the very ecstasy of presumption. But I have had a “call" to literature, of a low order—i.e. humorous. It is nothing to be proud of, but it is my strongest suit, & if I were to listen to that maxim of stern duty which says that to do right you must multiply the one or the two or the three talents which the Almighty entrusts to your keeping, I would long ago have ceased to meddle with things for which I was by nature unfitted & turned my attention to seriously scribbling to excite the laughter of God's creatures. Poor, pitiful business! Though the Almighty did His part by me—for the talent is a mighty engine when supplied with the steam of education—which I have not got, & so its pistons & cylinders & shafts move feebly & for a holiday show & are useless for any good purpose.

This epiphany marked a turning point. It was the moment when he decided to “drop all trifling, & sighing after vain impossibilities” and consecrate himself to the writer’s life. It was the moment when he accepted his inheritance as a child of the frontier: as a “low” humorist “scribbling to excite the laughter of God’s creatures.” Instead of trying to become someone he wasn’t, he would make peace with the person he already was.

His new self-knowledge didn’t solve anything in the short term. “I am utterly miserable,” he revealed at the end of the letter. “If I do not get out of debt in 3 months,—pistols or poison for one—exit me.” Yet he also felt a pinprick of hope: the New York Round Table had praised him for his Californian pieces, and the acclaim made waves when it reached San Francisco. “It is only now, when editors of standard literary papers in the distant east give me high praise, & who do not know me & cannot of course be blinded by the glamour of partiality, that I really begin to believe there must be something in it,” he wrote.

Out of this crisis came the courage to face the jumping frog. Eight months after he heard the tale at Angel’s Camp and promised to write it for Artemus Ward, it remained unfinished. Now he wrestled the manuscript into its final form and sent it to New York. By the time Twain’s contribution arrived, however, it was too late: Ward’s book had already gone to press. The publisher, George W. Carleton, passed the item along to Henry Clapp Jr.—a New York Bohemian who had once held court at Pfaff’s with Walt Whitman—and on November 18, 1865, “Jim Smiley and His Jumping Frog” appeared in Clapp’s Saturday Press. This wasn’t another sarcastic squib of the Bohemian school: it was a fable of the frontier, drawing laughter deep from the country's diaphragm, changing the course of American literature forever.

From The Bohemians: Mark Twain and the San Francisco Writers who Reinvented American Literature by Ben Tarnoff. Published by arrangement with The Penguin Press, a member of Penguin Group (USA), LLC. Copyright (c) 2014 by Benjamin Tarnoff.