“One of the constants of the feminist periodical across cultures is that it exists outside of the dominant mode of capitalist publishing.” In 1989, writing for Borderlines, the late Canadian literary critic and academic Barbara Godard spoke truth to power when it comes to the history of feminist periodicals. In 2015 these words were tweeted at cléo, a digital feminist film journal that I run with a collective of women. As a self-funded publication that relies on donations, cléo fits Godard’s definition perfectly. Yet her words are also reflective of a pre-internet reality.

In a digital era, the “dominant mode of capitalist publishing” has become far murkier. Feminist film criticism was once solely a product of academia or small-run publications, with limited reach and readership, and firmly stood outside of (and opposed to) much of mainstream film writing and culture. Now it can (and does) enter mainstream conversations with a click, @ or share. This can (and does) act as a corrective to the blindingly white and exhaustingly male culture of film writing. But it also poses a new challenge for feminist film criticism: the loss of its marginal stance as it’s co-opted into the very industry it has historically defined itself against.

*

Film is deeply wedded to capitalism. There’s not only the sheer cost of making a movie, but how capital is used to define a film’s success: the box office. While album sales and New York Times best-sellers lists chart the money-makers in their mediums, the discussions aren’t often around how many millions it took to get the cultural product made in relation to how much it raked in. For film, profit is often central to discussions, regardless of the amount. (Take Tangerine, the rightly celebrated indie darling of 2015, which became a talking point not only for its trans storyline and the fact that it was shot entirely on iPhones, but also because it only cost $100,000 to make.)

Not surprisingly, this close relationship to the bottom line affected the nature of film writing, too. The silent era saw the birth of fan magazines, which were folded into the industry machinery with the creation of the star system. The voyeuristic pleasure of a tabloid tale sells a magazine, which then fuels that star’s ticket-selling power, and on it goes, to this day, like an ever-ravenous ouroboros. As the film medium became more entrenched in popular culture, and as newspapers and other publications began to hire film writers, mainstream film criticism’s journey was one of working from the inner circle to the margins. Instead of lauding the stars and marvelling at new technologies, it involved sparring about taste, and, crucially, butting up against the basic premise that movie magic can be quantified by revenue.

In its most utopian sense, digital self-publishing promised to bring ideas from the margins to the masses.

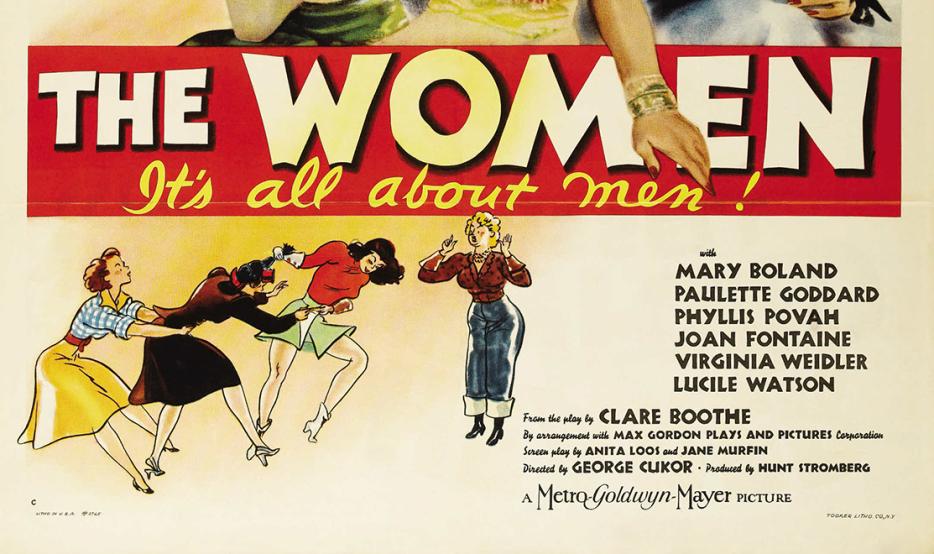

Feminist film criticism, by contrast, has different origins, removed from the pervasive power of the film industry: second-wave feminism. Take the grandmother of the feminist film periodical, Camera Obscura, which was launched in 1976 out of a discussion group of grad students at University of California at Berkeley and is now printed by Duke University. Its first issue states that the concept for the publication “evolved from the recognition of a need for theoretical study of film in [America] from a feminist and socialist perspective.” In its 40-year history, Camera Obscura has stayed true to this mandate, publishing pieces by the stalwart stars of graduate seminars like Kaja Silverman, Constance Penley, Mary Ann Doane and Wendy Hui Kyong Chun. Their work fits Camera Obscura’s idea that “feminist film analysis recognizes that film is a specific cultural product, and attempts to examine the way in which bourgeois and patriarchal ideology is inscribed in film.” But while Camera Obscura was born on the margins, it faces an issue that challenges academia regardless of subject matter: with costly subscriptions and limited hard-copy distribution, Camera Obscura only reaches the margins. Criticism such as this often caters to a certain, privileged set.

My own first encounter with feminist writing on film was at university. In a course on French New Wave Cinema, taught by the brilliant scholar Alanna Thain, the icons of cinematic history Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut were dismantled through a feminist lens; works of female filmmakers, such as Agnès Varda, were positioned as central. At the same time I was introduced to bell hooks and her cornerstone theoretical book on gender, race and media studies, Reel to Real, and Tania Modleski’s work on Alfred Hitchcock, which gave me a means to grapple with my love for this director’s often less than female-friendly films. I’m indebted to this time in my studies—and not just to the ideas I was exposed to, but also to my parents, who helped pay for the pricey course packs that held the printed pages that would come to shape me.

Had I been born a few years earlier, things might have been different: I missed the heyday of self-publishing zine culture in the 1990s. These publications were radical but also ephemeral. Zines were not preoccupied, as Western literary culture is, with an occupation of physical space in order to demarcate legacy—zines were made in limited runs, sold at shows, and snail-mailed to friends. While researching specific feminist film zines, I found mention of them in a collection owned by Amy Mariaskin, which is now part of Duke University’s Culture Zine Collection. With no PDFs or scans, I can’t read them unless I road trip to North Carolina. Access once again became an issue. The Internet was supposed to fix all of that, but the process of digitization is also a hierarchical one—one that’s not outside of the influence of dominant power structures that privilege recording the stories of certain races, sexual orientations and genders.

*

In its most utopian sense, digital self-publishing promised to bring ideas from the margins to the masses. I took this ideal to be true. I knew what I had missed in the 1990s and wanted to be a part of something similar. With cléo, I wanted to create something challenging, like Camera Obscura, but have it be open to anyone who wanted to Google it. And I’m hardly alone in this impulse—there are now a plethora of sites dedicated to women in film: some focus on the industry side, such as Women in Hollywood, which works to highlight emerging female voices in an industry that’s seemingly rigged to ignore them. There’s Bitch Flicks and Black Girl Nerds, which play a crucial role in highlighting popular culture’s blindness to race and gender. (See Black Girl Nerds’ Twitter takedown of the all-white cover of The Hollywood Reporter’s November 2015 issue.) Others sites are more invested in the spirit of empowerment through self-publishing, such as Willow Maclay’s Curtsies and Hand Grenades.

Though inspired by the radical thought of academia and the DIY days of zines, feminist film criticism on the Internet differs because of potential reach. Put another way, what’s different now is dissemination. Years ago I started a blog in my early twenties because I wanted to write about film. I wanted to write, I wanted people to read my writing, and I wanted people to hire me. The latter clause is hardly shameful; everyone has the right to make a living. But it has also meant feminist film criticism has become slippery in the digital age. While the Internet has made feminist film criticism more accessible (for those that find the internet accessible, of course), it’s also folded into the dominant mode of capitalist profit—the web itself. And, to riff on another great Canadian critic, the medium is starting to dictate the message.

*

The similarity between academic writing and zine culture is their disregard for the masses. Alternatively, on the Internet, numbers and reach speak—especially in a landscape in which, increasingly, reimbursement comes in the form of “exposure.” And it’s hard, even when self-publishing, not to consider which films and topics will attract more views. Questions that shouldn’t bear any weight in anti-establishment publications—Will this be alienating? Too hard? Too obscure?—are now on the table again. It becomes a chicken-and-egg debate of what came first: the SEO return on a feminist Star Wars thinkpiece or the feminist takes on Star Wars?

This isn’t to dictate what should or shouldn’t be written about when it comes to film culture. (Come at me with your views on Star Wars!) But my fear is that in a race for reach, feminist film criticism will lose its marginal stance. It will become, for the first time, folded into part of the industry’s machine instead of attempting to dismantle it.

“Feminist film scholarship,” observes Sophie Mayer in Political Animals: The New Feminist Cinema, “has been critical in maintaining an awareness of inaccessible films rather than seeking to institute a canon.” In a digital space, for all its seemingly inherent freedoms, feminist film criticism is at risk of joining the institutionalized conversations around a few films—the big, the blockbuster, but necessarily the bold. It’s at risk of playing to the canon instead of exposing what we’re (literally) not seeing. More voices drowning out the same old male white ones is a welcome sound to my ears. But, at risk of sounding paranoid, we need to be vigilant that the conversations we’re reframing aren’t just being folded back into the same system that’s bound to the box office. Publishing another piece on Star Wars, after all, still pushes ticket sales to Stars Wars.

This all also begs the question: while outlets are seemingly actively seeking female writers and writers of colour—see Sight and Sounds’ 2015 call for more women reviewing film—why haven’t mastheads, print and digital, changed drastically? Why does it take a radical call like Bardot Smith’s #GiveYourMoneyToWomen to challenge, as she says, the “notion that we have to only seek justice, safety and equal pay through [...] the male-dominated corporate world”? Or, in this context, why does legitimization as a female critic have to come through writing for publications that pander to industry whims or patriarchal tastes? Or through writing about films that are recognized by them? To me these questions demonstrate that digital reading and publishing habits mimic those of print. For all the talk of the widening of the world thanks to the web, those in positions of power are ultimately still seeking out ideas and frameworks they’re comfortable with, as writers, editors and as human beings.

There is a certain pride in resisting the pull of the centre stage—that lingering teenage rebellious impulse to define oneself against the norm. But more importantly, beyond any sense of self-satisfaction, is the simple fact that the margins are the ideal stance of critique, allowing for a vantage point to observe all that is wrong (and, I suppose, occasionally what is right) with society. “Where the active viewer makes connections to and within the film, the activist viewer connects the film and the world.” This is once again from Mayer, and I’ve written out this quotation and taped it to the wall by my desk. It’s a reminder to ask: in a world that posits endless access and knowledge, what am I, knowingly and unknowingly, not seeing, seeking out and reading? It’s a reminder, more than anything, to step back to the margins. It’s frustrating out here, and occasionally lonely, but the view is worth fighting for.

Correction: This article originally stated that Camera Obscura was founded at Duke University and misspelled the names of Alanna Thain, François Truffaut and Tania Modleski. Hazlitt regrets the errors.