On the scale of fun, writing a book is generally Type 3, in line with an arduous expedition where the stakes are preternaturally high and the participants bounce between excitement, dread, and terror. Live to tell the tale and glory surely awaits. But risk is essential when striding forth into the unknown and, once home, sharing your findings as truthfully as possible. As Colum McCann put it, “A writer is an explorer. She knows she wants to get somewhere, but she doesn’t know if the somewhere even exists yet. It is still to be created. A Galápagos of the imagination. A whole new theory of who we are.”

This time, like a ship-board cat on a long expedition, I was along for the ride, an editor providing companionship as much as keeping the mice at bay. Metaphors aside, that writer-editor relationship can sometimes turn into the deepest friendship. Type 3 fun, after all—if you survive it—forges powerful connections. And the banter that comes during the voyage can reveal profound truths while keeping a sense of play and possibility in the undertaking.

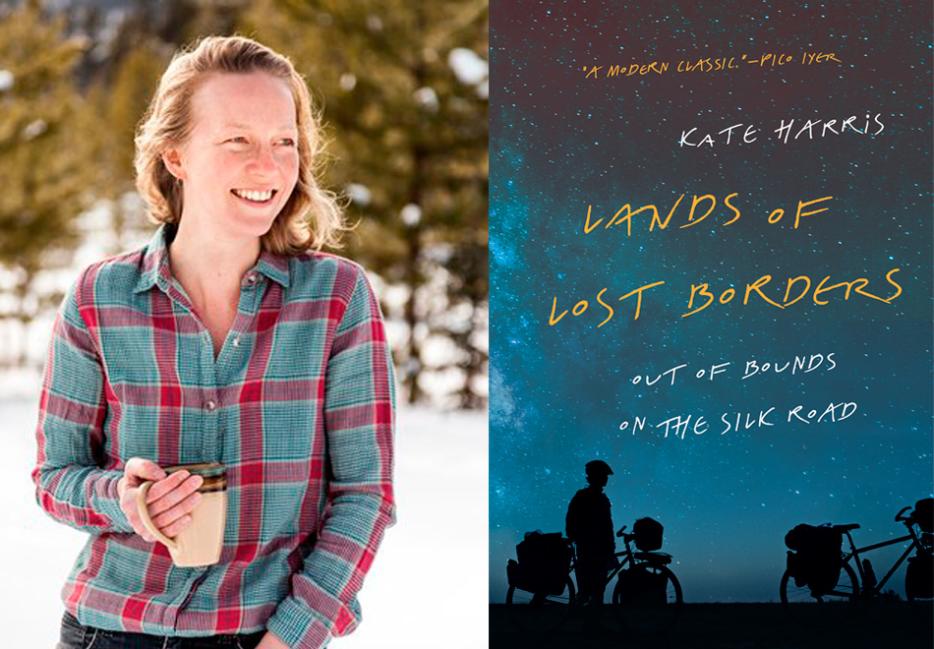

A shared love of adventure—particularly bike touring—initially brought Kate Harris and I together. Her new travel memoir, Lands of Lost Borders (Knopf Canada), is about biking the Silk Road from Istanbul to India, steering out of bounds and defying expectations as often as possible. Kate left behind her scientific studies and her hopes of becoming an astronaut and traveling to Mars in order to embrace the freedom she felt when exploring the Earth on her bike. I’m a long-time cycling activist and co-founder of The Reading Line, which offers annual literary Book Rides on two wheels. After completing the manuscript last summer, we hit the road, biking from Whitehorse, Yukon, to Atlin, British Columbia, where Kate lives.

A week before Lands of Lost Borders hit bookstores, we sat down to discuss the writing process, the idea of truth in memoir, Martian evangelism, and the role of travel literature. Fittingly, our conversation began in an airport and continued over Skype a few days later.

Amanda Lewis: So here we are, t-minus eleven days from publication.

Kate Harris: In a rush, in an airport, consuming massive quantities of sushi as if we’ve been biking all day.

But we haven’t. I’ve been driving and you’ve been sitting. That’s right, internet, I drive a car.

Oh, how the mighty have fallen.

Well, we had six months to prepare this piece but of course we’re doing it days before it’s due, between a visit to the vet for my cat and your flight to Atlin, because we’ve spent the last six months bantering about poetry and real estate, and going on adventures. It’s like this, Kate: sometimes when you’re under a magazine deadline, all you need is four wheels and the defogger, and the cat can’t come along.

It is exactly like that.

I’m a master of metaphor. I don’t know if you know this about me.

Where did this marvellous gift come from?

It’s probably an Irish thing. May you get to heaven a half-hour before the devil knows you’re dead. That’s an Irish blessing.

You’re an Irish blessing.

Thank you! Anyway, my metaphors don’t make sense but they’re soothing, and I feel like they help authors.

They do. They break the ice. Whenever we had editorial phone calls, your metaphors would make me laugh so hard I’d forget to be worried about writing. I remember going home after first meeting you, and trying to describe you to my partner. “She’s an eccentric,” I think I told her admiringly.

You were having this out-of-body experience when we first met. You were so over the moon because the book had been signed, but terrified because now you had to write it. You also thought we were punking you, because that’s a thing in Canadian publishing: we put all our money into punking authors. So, let’s talk about how this came about. The punking.

I was browsing the magazine rack in a bookstore in New Brunswick, flipped through a Quill and Quire issue, and found an essay by this editor who was into bikes and books and saving the planet. And this editor had worked on books by so many authors I admire: J.B. MacKinnon, John Vaillant. And I was like, “There she is. That’s my editor.” So I followed you on Twitter.

I checked out who you were when you followed me…

But you didn’t follow back.

[Laughs] Well, I’m verrrry choosy. That’s what the psychic told my mom. That her daughter is too picky.

Both too picky, and oddly accepting on the romantic—

Let’s not talk about that… Now I loved that you defied all the expectations you had set for yourself—to finish your PhD at MIT and become an astronaut on a one-way trip to Mars—in order to live more fully here on Earth, biking the Silk Road for a year with your childhood friend Mel Yule. Plus, I have such a fondness for that part of the world, and have been longing to visit Tibet, and your book transported me there in the interim. How do you see your book fitting into literature on that country, or the Tibetan freedom question? Do you see your book serving a political purpose?

I certainly don’t write to offer political solutions, or solutions of any sort, but to provoke questions, to reveal ambiguities in realms where black-and-white thinking tends to prevail. What’s happening in Tibet now is what has happened and is happening to Indigenous peoples in Canada, and in colonized lands all over the world: the loss of autonomy and sovereignty and culture, the imposition of a foreign language and foreign laws.

Throughout the book, but especially in Tibet, I wanted to examine the troubling repercussions of “exploration,” an enterprise with such strong imperial overtones, such strong associations with flags and maps and claims. The book doesn’t offer up any grand solutions, because frankly I don’t have any to offer other than, why can’t we all just be better to each other? Which isn’t exactly a policy you can just implement. So, the book shows what’s happening with the Chinese occupation of Tibet as far as I could see it—which, to be honest, wasn’t very far when we couldn’t really even talk to Tibetans.

Right, because you and Mel were disguised as androgynous Chinese cyclists in order to sneak in without a guide or permits. You’re back in your off-grid cabin in Atlin now, where you live. But you split time between there and Toronto, where your partner, Kate Neville, is a professor of environmental politics at University of Toronto. How do you reconcile those two extremes? Being this wanderer who is happiest in wild places, and then living in downtown Toronto for months at a time?

Well, most of my extended family lives in Ontario, and my brothers are in Toronto as well as Mel. So people-wise, it’s a joy to be there. I try to binge on what Toronto has to offer and Atlin lacks, namely easy access to libraries, museums, films, talks, cultural events. Poor Kate has to slog away at being a professor, she’s really busy, but as a freelancer I can take advantage of all the city’s marvels. Even so, it wears on me after a while. I feel my senses shutting down: there’s too much noise, too much input. I can read well in cities, but my writing feels cautious and closed-off. It’s so easy in Atlin to be inspired. If you can’t write something decent in this splendour, all this fresh air, there’s really no hope. As someone who spends a lot of time alone in a cabin in the woods, though, I can attest that Toronto is a much more solitary and anonymous place. I mean, you saw Atlin: it’s incredibly community-oriented, but at the same time, everyone’s an artist or adventurer. They understand the hermit impulse, the need for solitude and extremes, but everyone looks out for each other. You’ll be invited to dinner parties every week.

I don’t know if you remember me saying this to you when I was staying with you in Atlin, but you can sense that everyone’s an artist there, it’s vital, it’s in the air. People are working for that above having a paycheque or a fancy house. Those aren’t the markers of success there. I was really struck by that.

And in Toronto, the baseline for keeping life going is really high. Of course people are focused on careers: there are bills to pay, and they’re expensive. But you can dirtbag it in Atlin and lead an incredibly rich life so long as you’re willing not to make any money. Because what is money for if not living the life you want? That’s the attitude in Atlin.

And ultimately, it doesn’t matter what it costs, because the cost of not being there is so high: you’re not doing your best work.

That’s right. Creatively, there’s a cost to being away. It’s like I access the fullest, most elemental version of myself in Atlin. Everywhere else I’m only partially expressed.

Can we talk about the epigraph to your book? It’s from The Waves by Virginia Woolf: “To speak of knowledge is futile. All is experiment and adventure. We are forever mixing ourselves with unknown quantities.” I know you’re a huge Woolf fan, so I wasn’t surprised to see this, but someone picking up a travel book might expect lines from another travel book, or something from T.S. Eliot. What does this epigraph have to say about the way you see the world, travel, writing?

The Waves is my all-time favourite Woolf book, a gorgeous prose-poem of a novel that wrestles with life, the universe, everything. It’s probably the least-read or least-talked about of her books, so I was thrilled to stumble on an essay by Jeanette Winterson, in her collection Art Objects, that articulates some of why I loved it so much. Winterson writes, among other things:

“The Waves…is a strong-honed edge through the cloudiness most of us call life. It is uncomfortable to have the thick padded stuff ripped away. There is no warm blanket to be had out of Virginia Woolf; there is wind and sun and you naked. It is not remoteness of feeling in Woolf, it is excess; the unbearable quiver of nerves and the heart pounding... To read The Waves is to collide violently with a discipline of emotion and language that heightens both to a point of painful beauty.”

Yes. Exactly. All of that. What I found in The Waves is what I seek from travel: that rapture, that exposure, that sensation of having the thick padded stuff ripped away to reveal the truth of where and who we are, or less the truth so much as the mind-boggling mystery at the heart of everything.

And the experiment part of that epigraph speaks to your scientist nature. You had this desire to go to Mars. It seems this is how you live life: you have this romantic, poetic side, but you’re also a hypothesis tester. You ask questions, you experiment, you deal in the tangible. You build sheds, for example, on your property in Atlin.

I asked a lot of questions of YouTube during the building process this past summer. How do I lay a foundation? How do I square a subfloor? What is the meaning of life, YouTube?

Right! You jest, but in fact you’re always asking yourself that, about the meaning of life, and your life. You’re always asking, is my life moving in the direction I want it to? And then coming up with an answer and acting on it. So you tried out this hypothesis of: I want to go to Mars because it will fulfill me in every way. And then you tested it during a Mars mission simulation in Utah, and then at MIT, and then said, nope, this experiment is flawed.

Doomed, in fact. I was a disaster in the lab, far too distracted by whatever was out the window. But yeah, one of the things that blew my mind when I went off to Oxford to study the history and philosophy of science, instead of doing science myself, was how partial and incomplete and open to revision it is. For a time we understood gravity through Newton’s Laws, then Einstein came along and we saw the “truth” of gravity in a whole new way. Until Oxford, I’d always seen science as the ultimate tool for deducting truth, and I mean capital-T truth. Then I read Thomas Kuhn’s Structure of Scientific Revolutions, among other books on the philosophy of science, and came to understand how paradigm shifts can be prompted by a pretty irrational process.

One scientist will fiercely advocate for one theory, because she has a hunch that this is how the world works, it seems elegant and sensible to her, though she can’t definitively prove it. Another will argue with equal fervor that his totally different theory explains a given phenomenon best, though he can’t prove it either. And those different beliefs, different theories, battle it out over time until the facts fall more on one side than the other. This faith at the core of science really shook, well, my faith in science. I no longer saw it as the only way to genuine knowledge. There are so many ways of knowing the world. Woolf nailed it, as she nails most things: all is experiment and adventure.

One of the most challenging aspects of writing a memoir is wrestling with that element of “truth.” Because your story, of course it’s “true,” but who you were when you biked the Silk Road the first time, before Oxford, versus who you were when you picked up your route where you left off, five years later, versus who you are now when you’re writing the book—I’m curious about how you wrestle with that idea of truth when you’re writing about different versions of yourself. In The Night of the Gun, David Carr writes about a pivotal night in his life. Here he was, as he believed himself to be at the time, a respectable journalist and doting father, and yet he found himself completely strung out and pulling a gun on someone. So he went back and started investigating his own life, and talking to people who were there, because he had a certain perception of who he was, and he wanted to test that, sort of triangulate towards truth. So I’m curious about what your process was like in writing the book. I know you kept a journal, and you had Mel as well to bounce the story off and fact check. But how did you go about balancing Kate as she was with Kate now, and the Kate that appears in this book?

Hmm, different versions of myself. It’s interesting, looking back at my childhood…obviously I’m aware that I was into Mars as a kid. But when I went back and actually re-read the letter I wrote—

Tell me about the letter.

I wrote a sort of manifesto as a teenager calling for a mission to Mars as the highest priority of humankind. And I fervently, wholeheartedly believed every word of it, so much so that I sent it to twenty-two world leaders. I was an evangelist for Mars. In a way I admire that zealous younger me, who felt with such conviction that going to Mars was the one goal worth striving for, worth putting all the world’s passion and energy and resources into.

Which gets at what you were saying about faith in science.

Right. Faith is a tempting, comforting thing, if you can find it. I’m so glad I aimed for Mars when I was younger. I pretty much owe everything I’ve done and seen and learned to that singular focus. But it was the kind of faith that was begging to be shattered by the complexity of the world. A world I hadn’t seen much of as a kid, except through books. So, as unworldly as I was, it was easy to believe that the Earth was a write-off, a ruined planet, and that Mars was the great hope.

Of course, once I finally had the chance to travel for myself, I saw that our world is both better and worse off than I thought. There’s so much beauty and wonder and hope still left here, as harsh as things are for many people, and many places. By any reckoning, this planet is the best thing we’ve got going in the universe. To not put all our energy into being good “earthlings” seems insane now to me.

To be fair, though, I wasn’t just enchanted with Mars as an escape route: it struck me as the one place in our solar system where science and poetry and philosophy might meet, by yielding an answer to that age-old question, Are we alone? That was thrilling to me, and is still thrilling to me. I’m glad we’re asking that question, sending out probes and rovers in hopes of inklings or even answers. But Mars is no longer my messianic be-all and end-all. It’s one of many places that makes the universe interesting.

Now by the end of the book—spoiler alert—you’re emaciated and exhausted and your friendship with Mel is momentarily strained if made stronger in the long run, and at this point you started to formulate a vision for life after the Silk Road. You’ve ended up at this spot in Atlin, bordering Alaska, the Yukon, and BC, borders that don’t really matter because you can’t see them and you cross them all the time when heading to Whitehorse to buy groceries, for example. And you’re writing in this tiny cabin, and you’re considering these grand questions: what is truth, what is the state of the world, how am I taking care of my postage-stamp piece of it. And as we’re talking now on Skype, I’m looking at that Judy Currelly painting over your shoulder on the cabin wall, watching it as the light changes, and it’s glowing: three ravens around an orb, circling it almost like spacecraft, and it’s called Ravens Discussing the Affairs of the World. I see your book as just that: a kind of probe or spacecraft you’ve sent into orbit from your base in Atlin, asking some of the biggest questions: Who are we? Are we alone? What are we doing here? Wait, why are we on this mission? Abort! ABORT!

[Laughs]

So that’s how I see it. In fact, one of the things I admire about you is your optimism. You don’t let the horror of the world crowd out the wonder. What I’m circling around here is the relentless quest for truth you seem to have, which is informed of course by your scientific training, and now comes through in your writing. And also in the writing you love and share, since we’re always flinging bits of essays and poetry and interesting articles back and forth. Though you tend to start your days reading things like the Paris Review or Granta, and I tend to start my days reading Apartment Therapy.

You and I, we bring such different riches to each other! I’m less interested in truth, though—whatever that is—than in being aware, at all times if possible, of the wildness of being at all. Goethe said the highest goal humans can achieve is amazement, but when you think about it, amazement is a pretty low bar given the facts of the matter, namely that we live on a spinning hunk of rock in an undistinguished corner of a universe full of stars, and we haven’t the faintest idea where it all came from. How is it that we aren’t wonderstruck by existence every second of every day?

You are, as your book shows. Now this is your debut book, and it’s a travel memoir. Are you worried about being pigeon-holed as a travel writer, a memoirist, the next Cheryl Strayed or Elizabeth Gilbert?

I’m more concerned about being pigeon-holed as an adventurer who happens to write, when really I’m a writer who happens to enjoy grueling sufferfests from time to time. And I have nothing against Cheryl Strayed or Elizabeth Gilbert.

Of course not! They’re amazing writers. People are quick to write them off due to their success, which is garbage. They are successful primarily because they are sublimely talented, and they continually hone their craft. Also, Dear Sugars for life.

Yes, they’re gorgeous, engaging writers, and I suspect we’d all be best friends if they’d only give us the chance. In part because we’re hugely different. What made those two hit the road, so to speak, was an emotional crisis of some sort, and travel was its cure. This is a valid reason to travel, but there are so many other valid reasons! Including a basic curiosity about how billions of other beings on this planet are going about their lives right this second. So if I must be known as a travel writer or a memoirist, I hope such labels are less associated with inward self-discovery, and more associated with looking outward with longing.

When men write about travel, the press and general public tend to focus on their derring-do and bravado, or on the nature and culture of the places they travel through. When a woman does the same trip, she’s expected to write about her feelings or her relationships. Your writing has been compared to Rebecca Solnit and Pico Iyer, and I feel like all three of you have this wide-eyed yet pragmatic take on the world. It’s not about “me, me, me.” It’s about us as a species, as members of a global community. You’re all satellites going forth into the universe and reporting back. Every time I finish reading your book, and I’ve read it many times at this stage, I don’t feel like I’m closing the story of your life. I close it and feel like my life is more expansive, things seem more possible. The world feels smaller yet larger at the same time. Now, I’m curious about the photos in the book. They’re not of you or the adventure so much as the people you met and places you saw along the way.

All of that was really important to me. If there were going to be pictures at all in the book, I wanted them to be evocative, not illustrative. To enhance the text instead of just depicting it. The initial selection of photos by the publishing house tilted toward the adventure and Mel and me, but I didn’t want the places we travelled and the people we met to be consigned to the background. The point of including photos wasn’t to satisfy people’s curiosity about, say, what Mel and I look like, or what equipment we brought, you can Google all of that, and any other important details are included in the main text. No, the point of the photos is to spark more questions than they answer—much like the book as a whole, I hope.

Anytime I can grab someone’s ear about your book, I highlight how it’s about defying the rules we have for ourselves, and crossing boundaries. In the narrative, you literally cross a border when you sneak illegally into Tibet. And you more metaphorically cross boundaries when you step off the scientist/Mars track you were on. How do you bring that same sense of risk-taking and border-breaching into your writing?

In all my travels, I’ve never done anything nearly as perilous as facing a blank page on a daily basis for years on end after returning from the Silk Road. Writing means risking failure, courting it even. Setting off for territories that might not exist. Working away for half a decade on a project that might never find a publisher. And when you write, much as when you travel, you can’t be too conscious of the risks you’re taking. You can’t let prudence overrule a healthy sense of adventure. You sit as many risks as you run, isn’t that the saying? So you might as well run, or bike, or approach writing with a sense of play and trust and hope, despite the leering risk of failure, because it’s way more fun.

On that note, I want to talk about vulnerability. There’s a lot of it involved in striking out on an adventure, or putting a pen to the page. Until now, only a handful of people have read your book. Soon you’ll have strangers giving it star ratings on Goodreads! How are you handling the imminent exposure?

With total aplomb. Meaning I veer between ecstasy and terror from moment to moment, which is really fun for my partner. At the end of the day, I feel proud of the book, I gave it everything I had, and now it goes off to live its life, all grown-up. It kind of feels like giving a gift to the world, though of course this doesn’t guarantee it’ll be received as such. My hope is that it moves people, revives their sense of wonder, makes them fall in love with the Earth so that, like me, they never again want to abandon it for Mars. Above all, I hope it makes people want to explore—not the Silk Road, necessarily, but whatever territory is available to them. It’s scary and alluring, this promise and threat of feedback on the book after years and years without much of it. I grew up chasing gold stars, the highest grades, and that’s a hard impulse to kill. The actual writing of the book was a healthy exercise in ego extinguishment. But publishing a book threatens to put the ego back in play or kill it off forever. So I’m trying to detach myself from outcomes and focus on the next experiment, the next adventure. Godspeed, little book. You’re on your own now.

I think it was Atwood who said that once a book is published, it doesn’t belong to the writer anymore. It belongs to the reader, it takes on its own velocity. And what was that Steven Heighton quote you shared with me that I can’t remember now but I love?

Oh, it’s so good! And so true of both travel and writing. “Resign yourself to the road, there’s no arrival. There’s no map either, come to think of it, but the sun is rising and the radio is on.”