As a kid, I mostly ignored the Canadian history I was taught. It struck me as flat. Where was our fight for freedom, our revolution? Not only did I want a clearly defined enemy, I wanted to see the unmistakable bastards driven into the sea at the end of gleaming bayonets. High above, the rockets red glare and bombs bursting in air.

That’s what I wanted, what the Americans had—the chance to gaze heavenward (at a bullet-riddled flag, an indomitable eagle, a sky ablaze with fireworks) and feel inspired by a more perfect union.

Canadian history is not the problem. It’s fine and well, for what it is—but it’s not what we need. What we deeply need is a heightened sense of who we are and why we’re here.

But let’s back up. There I was, a typical Canadian kid, ignoring the Canadian history I was taught and growing up to be, more or less, patriotically agnostic. I didn’t think about Canada much, nor do most Canadians probably; instead, we tend to focus on our careers, relationships, friends, enemies, yoga, music, working out, getting high, being nice, shoveling snow, staying in, hating war, loving the ozone, ignoring strangers, paying taxes, reading labels and vigorously flossing.

Then, one day, I was handed a hard drive and my attitude toward Canadian history—my agnosticism—forever changed. It was the spring of 2010 and I was working as the editor-in-chief of the web-only Toro Magazine. The guy who handed me the archive was my old pal real estate tycoon Chris Bratty (we had co-founded the digital Toro back in 2008), and the USB that he passed along contained about 22,000 photos of Canada that had been somewhat miraculously preserved in the archives of The New York Times. Chris had purchased the archive—the actual photographs, boxes and boxes of them—and thought I might be able to use the images in our digital lifestyle magazine.

So there I found myself, the happy recipient of a vast, dazzling, one-of-a-kind photographic chronicle of Canada’s evolution over the course of the twentieth century by The New York Times. What was it like to first explore this cultural treasure trove? Fantastic. Mind-blowing. Here, finally, was the raw material upon which one might construct a defining national myth. Even more astonishing, not only was it a chronicle of Canada’s development as a nation, it was also a record of how we’d been perceived by America. In a remarkable twist of fate, the very country whose super-sized culture had so often threatened to overwhelm our national identity had, in the final analysis, created a lens through which we could see ourselves more clearly.

Here’s a little of what I saw.

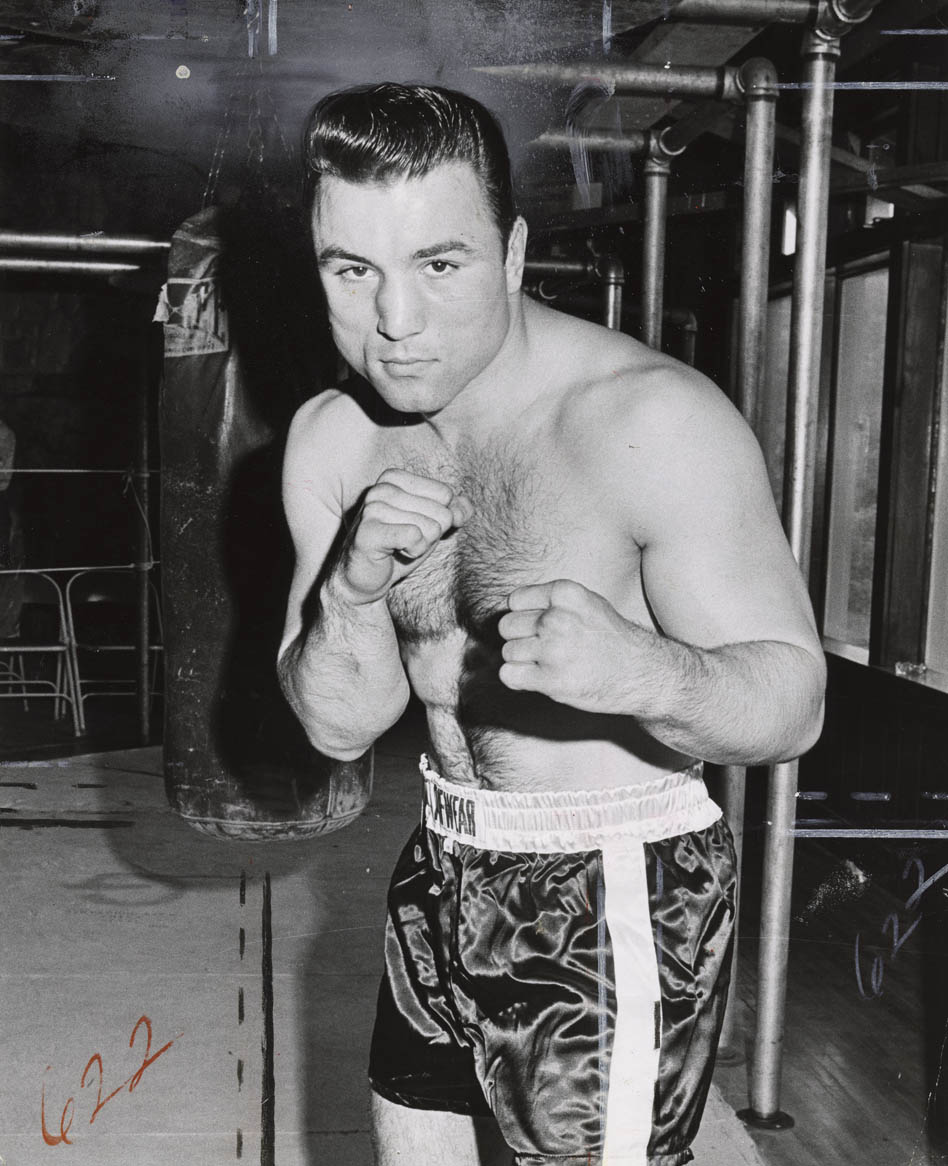

Gaze upon Canadian heavyweight champ George Chuvalo forever frozen in time—late July, 1967, looking every inch like a character that a young Marlon Brando might have played. He is way beyond old school, more like the father of Sparta, a son of Zeus by the nymph Taygete. He will hit you hard. He will not go down, not even to Joltin’ Joe Frazier, who Chuvalo will battle that very night. It is 1967, the Summer of Love. Race riots break out in Newark, New Jersey. The People’s Republic of China successfully detonates a hydrogen bomb. The British Parliament decriminalizes homosexuality. And Canada turns one hundred years old.

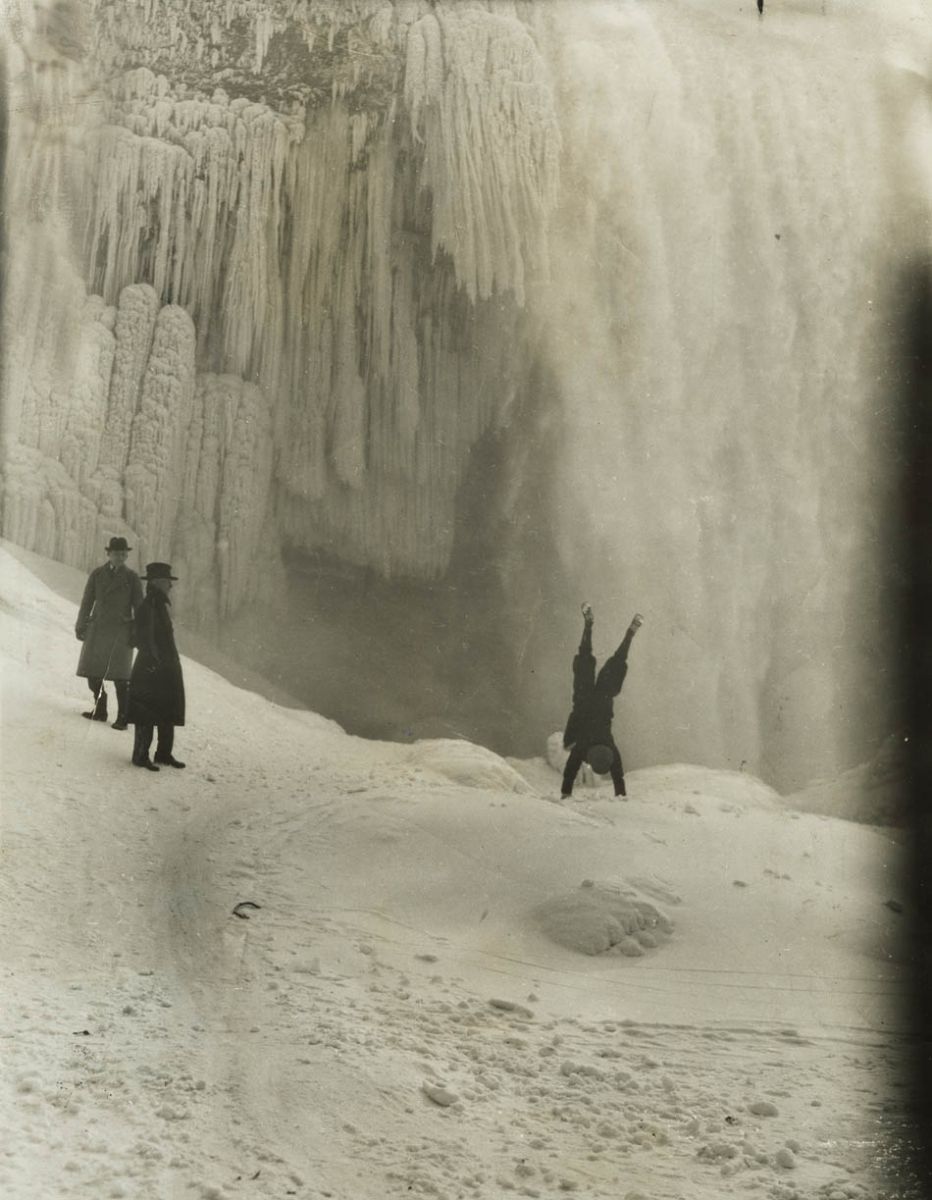

This shot is a wonderful mix of grandeur and unreality, like something an ice giant might have dreamed. It is January, 1924. The two men at the left have the curious stiffness of many adult males photographed in this era, but look at the delightful insouciance of that handstand – why, he hasn’t even bothered taking off his newsboy cap! Perhaps he’s an actual newsboy? Hard to say. The backdrop is frozen, the men too. But the kid acrobat is cheeky, exuberant, red-blooded, pliable, free-spirited, free.

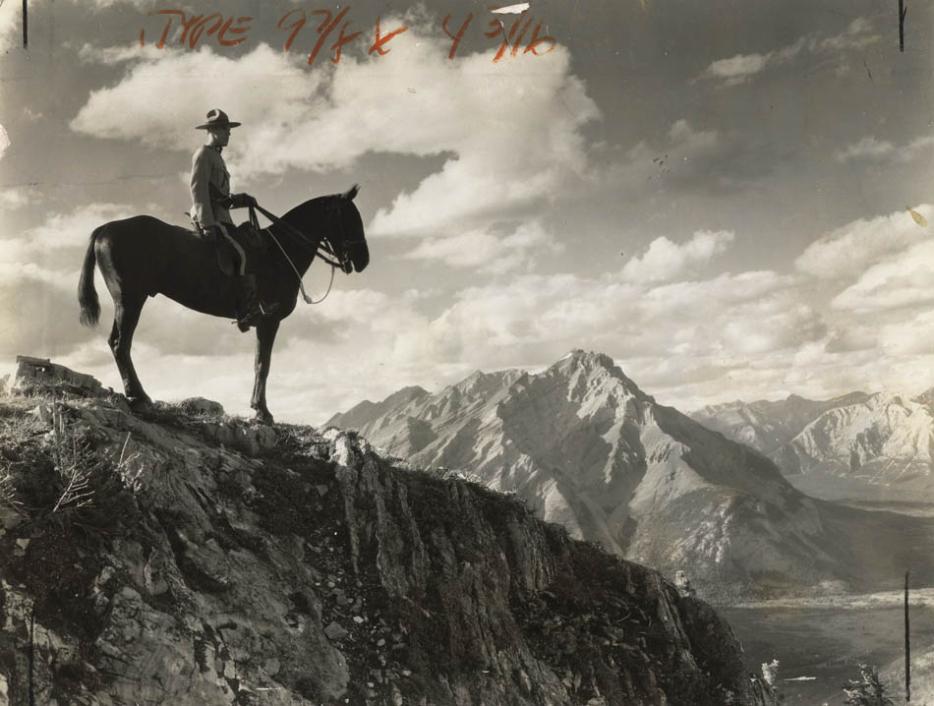

I don’t know why, but Louis Armstrong’s joyful trumpet solo about two-and-a-half minutes into “Star Dust” seems like a fitting soundtrack for this image of desolation and danger. Can you hear it? No, not Satchmo’s pealing horn but the ghostly wind yowling off the coast of Labrador circa 1930 and the clacking of the film stock as Varick Frissel records the crew of the SS Viking on its annual seal hunt. On this particular ill-fated voyage, the ship will get trapped in ice. The next year, a cache of dynamite will mysteriously explode, obliterating the Viking and killing twenty-seven men, Frissel among them. Armstrong, wiping sweat from his brow, shuts his eyes, blows.

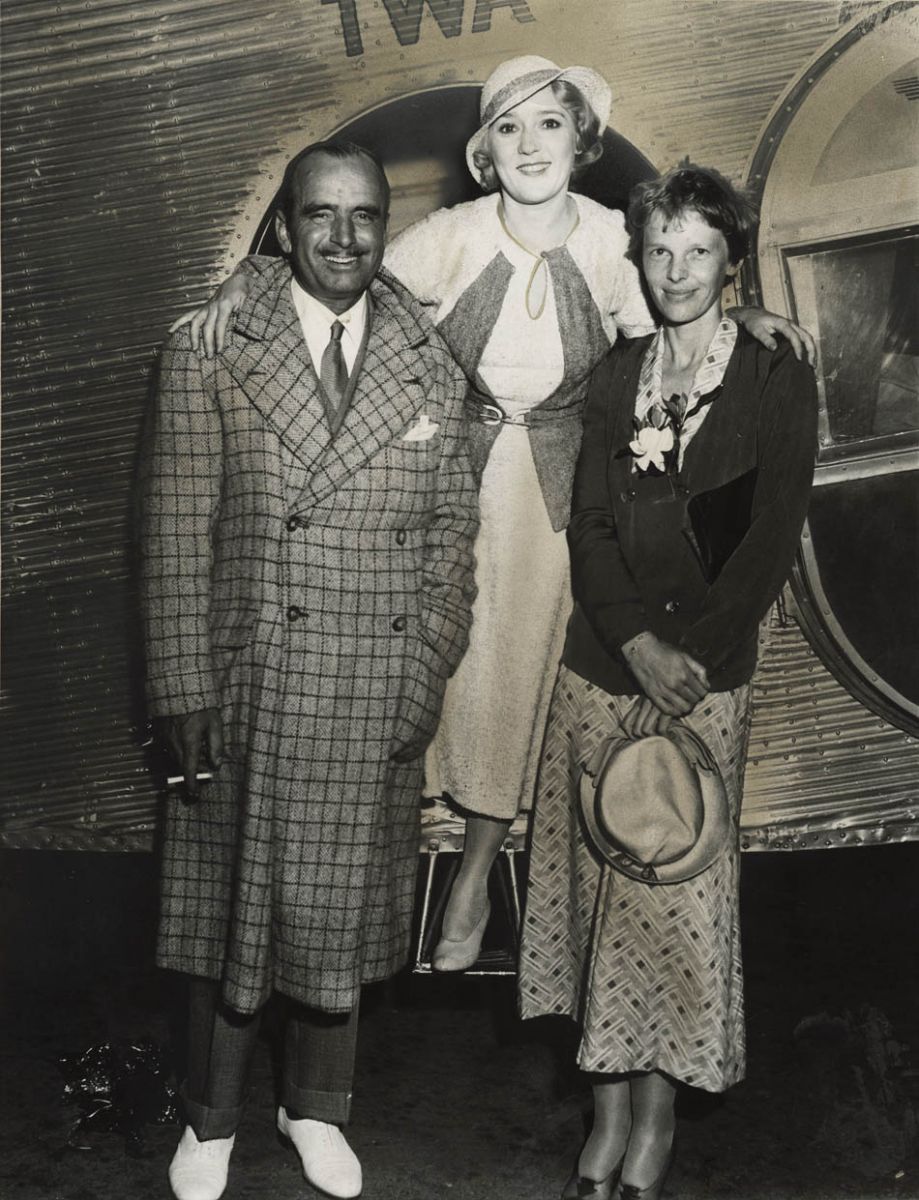

This shot from 1932 offers perspective on our celebrity-obsessed age. Here we have movie star Douglas Fairbanks, screen legend Mary Pickford and famous aviator Amelia Earhart chumming around at an airport in Los Angeles. Pickford (born Gladys Marie Smith in Toronto) eventually became “America’s Sweetheart,” by far the most famous woman of her day.

In fact, Pickford and Fairbanks were like the Pitt and Jolie of their time, with a 56-acre Beverly Hills mansion known as Pickfair (a precursor of celebrity uni-names like Brangelina and Bennifer) where they hosted gala parties for the likes of Albert Einstein, Charlie Chaplin and F. Scott Fitzgerald. While touring to promote Liberty Bonds in 1918, Pickford and Fairbanks embarked on a whirlwind affair. They married a few years later and were mobbed by fans while honeymooning in Europe, riots breaking out in Paris and London.

This photograph captures Pickford and Fairbanks four years from divorce; in time, their careers would fade as the silent film era came to an end. America’s Sweetheart would later battle alcoholism and a fractious relationship with her children. But here, on a bright day in Los Angeles, stepping off a TWA flight, greeted by her jaunty movie star husband and high-flying friend, life is good.

For some reason (the symmetry of the composition, perhaps?) the borders of this photo reminds me of the edges of a box; it is, for me, like gazing down into a container of young faces. And when I further reflect that many of these fledgling pilots will soon be killed in action, I often feel that I am gazing into a coffin. It’s an odd perception, I know; distressing. It’s even more heartbreaking when you consider not only their youth but the individuality of each and every face—singularities of expression and character underscored by the rows, uniforms, hierarchy. It’s the kind of photograph that draws you in and invites you to contemplate who each of these men were and what they were like. This snapshot records the first squadron of the Royal Canadian Air Force as they arrive in England in the early 1940. A few months from this moment, these men will be battling the enemy in the skies over Europe. Some will return home to Canada, many will not. But here, in the temporary enclosure of a photographic box, they shift, muse, tremble, live.

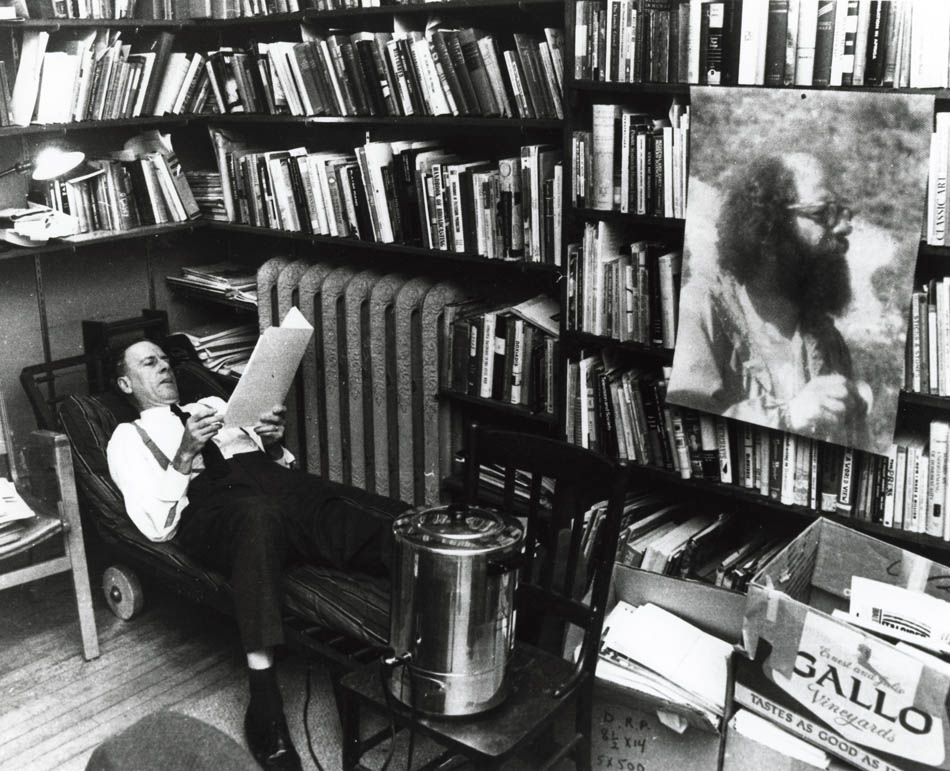

The big coffee maker awarded its very own chair, like a prize pupil. The empty case of Gallo wine (did he, the great man, work his way through each bottle?) The oversized photo of American poet Allen Ginsberg, looking every bit as mad and disheveled as McLuhan looks conservative and buttoned-down: pallid skin, drawn face, thin suspenders, short black socks. And yet, as managerial as he appears, McLuhan was among the most visionary thinkers of his generation, certainly more influential than the mystical Ginsberg or any of his Beatnik brethren—with the exception, perhaps, of William S. Burroughs. Burroughs and McLuhan were stylistically in sync, avant-garde intellectuals who dressed like squares.

McLuhan churned out media theories that foresaw a time—our time, this moment—when the medium itself would dominate the messages pulled in its wake. McLuhan, lying there stiffly on his stiff chaise, warmed by the radiator, fortified by an esoteric library, saw it coming. Burroughs, too, foresaw our moronic inferno. His outlets were guns, heroin, orgone accumulators. McLuhan turned to books, solitude, percolated coffee. America and Canada, side by side.