In 2014, The Governor General’s Literary Award for English-language children’s literature was awarded to When Everything Feels Like The Movies, written by then relatively unknown author Raziel Reid. The book, narrated by gay teenager Jude Rothesay, was inspired by the life and murder of fifteen-year-old Larry Fobes King by a classmate in Oxnard, California, in 2008. Though the book received critical praise, its unflinching depictions of sexual exploration in the high school set led to immediate backlash from conservative pundits. “It is fair to say that Jude’s sexual yearnings [...] constitute the bulk of the narrative,” wrote Barbara Kay in the National Post under the headline “Wasted tax dollars on a values-void novel.” A similar column appeared in the Toronto Sun by Brian Lilley, who admitted to not having read the book, and Ottawa author Kathy Clark circulated a petition to strip the book of its award. The critics emphasized that such subject material was inappropriate in a children’s book, though Reid’s book was always marketed as young adult, meaning it is intended for teenagers.

“These discussions never seem to extend to teen movies,” he tells me over the phone from Manitoba while visiting family (he lives in Vancouver). We had been talking about the adult books we read as teenagers, and how little would stop us from seeking out the stories we were interested in. High school movies, even (especially?) those that aren’t necessarily dealing with Big Serious Issues, have typically been allowed to be blasé in their depictions of sex.

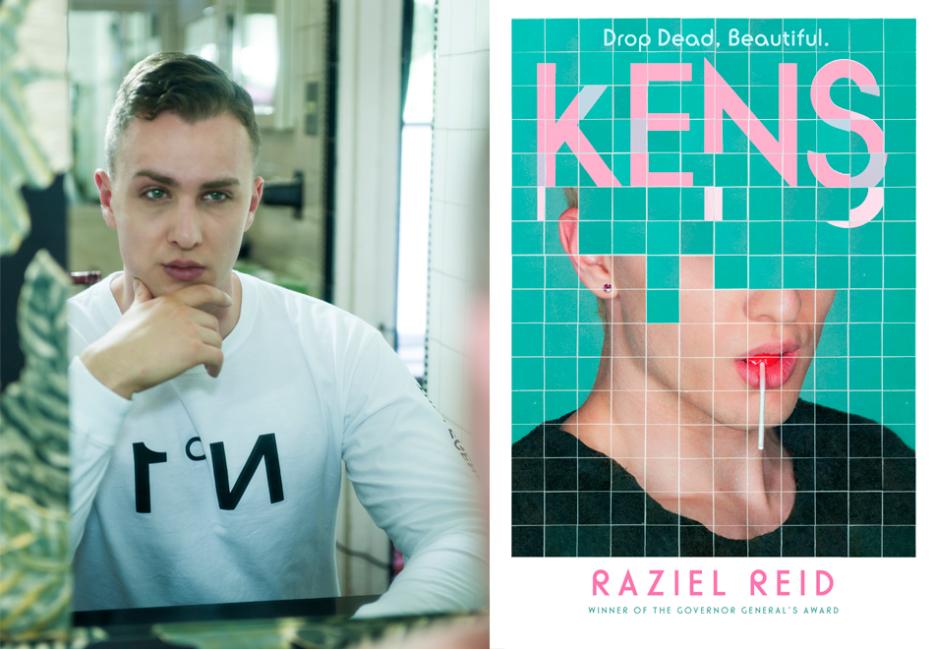

Reid had these movies in mind when writing his recent young adult novel, Kens (Penguin Teen). The influences are obvious; his book is to 1988’s Heathers what Clueless was to Jane Austen, taking loose inspiration from a classic story to recontextualize it for a new era. Willows High is ruled by leader Ken Hilton and his clique, Ken Roberts and Ken Carson, “created from the same mould, soul sold separately.” Shy Tommy Rawlins is offered what he believes is the shot of a lifetime when he is chosen to be given a makeover and made into the latest-edition Ken. While the sharp one-liners that made up When Everything Feels Like the Movies abound in his latest work, Reid trades in the gritty realism that Jude tried so desperately to escape in favour of a deeply artificial, deeply disturbing, deeply sparkly dream world. Kens is as frothy as it is heavy, and the already dark themes that underscored Heathers reaches a new gravitas in our current dystopia.

Anna Fitzpatrick: How long have you been living in Vancouver?

Raziel Reid: I moved to Vancouver in 2011. I grew up in Manitoba, and then I took a Greyhound bus to New York City when I was eighteen, which inspired Jude's dream in When Everything Feels Like the Movies to get on a Greyhound and move to Hollywood. I still have that dream. I went to New York, I went to film school there, I lived in New York for almost three years and then headed to Vancouver. I wasn't going to stay in Vancouver, I was just going to visit a friend, but I picked up a copy of Xtra Vancouver, which is now defunct. It's still online but it's not in print. I opened it up and this columnist was advertising for his replacement. He was a social columnist. I thought, I can party, and I can be friends with drag queens. I submitted some writing and got the gig. It was my first time getting paid to write. I decided to stick around Vancouver for a while, and it ended up being five years. I went to Europe for a while, and now I've been back in Canada for a year.

Where in Europe?

I went to the UK first for the launch of When Everything Feels Like the Movies. Little, Brown published it there. I went to Germany for the German publication, and it was also published in Austria and Switzerland. I went to Hungary. I spent a year living in AirBnbs.

What was the European response to When Everything Feels Like the Movies?

It was interesting, the conversation around the work really centred around class in a way that it didn't in Canada. I think there was a lot of discussion about the content, and the type of youth I was depicting, but it wasn't exactly contextualized. In Europe, I think the class system is so much more defined, and of interest to people. I found that the reviews and the interviews I had there really centred around the class I was depicting, and touched a bit on my own background and how the story came from that place. I’m literally Zoolander—I grew up working class with a nickel miner father.

And then you have Kens, which is a completely different setting. You set it in a fictional place, but it feels very Beverly Hills.

I wanted it to be the original fictional hometown of the Barbie Doll, and when she first came out, she was set in Willows, Wisconsin. I had created a Barbie World, but it was inspired by this idea of superficial California. And obviously there's like, the Malibu Barbie influence. As I was visualizing the world, even though I was setting it in Wisconsin, I kept on thinking of that California coastal type of place. The book obviously isn't about Wisconsin, I don't know anything about Wisconsin, it's just about Barbie.

What was your own high school experience like in Manitoba?

I just hung out with artists and misfits. We had fun. It was really bohemian. I didn’t go to school very often. I skipped class a lot. My school was right next to the Assiniboine River. I used to just go and sit by the river and do a lot of writing. I certainly found the society we were building among the students to be absolutely terrifying. My birthday is in January and as soon as I turned eighteen I wanted to move to New York City to be a star. Kelvin High School let me do my last term through online courses but I didn’t complete them. I have 28.5 credits instead of the 30 required to graduate. So I’m technically a dropout like another Kelvin alum, Neil Young. Down by the river indeed!

What books were you reading?

Luckily my mother was a voracious reader, so she had a lot of books for me to read. I read a lot of adult fiction. American Psycho was definitely my favourite. It remains my favourite book. After I read that, I read all of Bret Easton Ellis's books. I'm obsessed with him. The Poisonwood Bible, I read that. Alice Munro, I used to read in high school. Tom Wolfe, I read a lot. F. Scott Fitzgerald.

A lot of glamorous but depressed people.

The beautiful and damned!

Your book has been described as an homage to Heathers, but at times it's like a full-on remake. You've recreated some full scenes. How did you approach such iconic source material and make it your own?

I didn't try to remake Heathers because I think that's impossible and I'm obviously obsessed with it as a cult classic. I so believe in it. I really just wanted to capture the energy, the satirical vibe, and the edgy attitude towards high school that Heathers represents. Ultimately I think it's a different story that turns into something really opposite and unique from Heathers. I'm constantly just taking information and inspiration from around me and manipulating it.

Aside from Heathers and Barbie, what were some other big inspirations for this?

Well, my '90s childhood and all of the teen movies I loved, starting with Clueless, the first film I fell in love with as a kid. My older sister had a VHS of Clueless, and when I was five I used to watch it obsessively. Other movies like Sugar and Spice and She's All That, Mean Girls of course. Jawbreaker. I loved the iconic teen story with the clique of mean girls who rule the school. I always wanted to be the Regina George character because she was blonde and pretty and dating the hottest jock. Then I started to imagine what the highschool of the future might look like with that dynamic. Wouldn't it be interesting if that clique of mean girls was a clique of bitchy blond gay boys? In that way I removed the distance between me and the queen bee, or between people like me and this traditionally popular clique.

In teen comedies, the gay male character is usually the sidekick. If they're front and centre it's usually a tragedy, so it was interesting seeing these characters leading a dark teen comedy. There are so many great lines in this book, but at one point you have this teenager Claude from Idaho who looks up to the Kens, and you write that they're his biggest inspiration because they're "so post-gay it's sickening." I think that encapsulates so much of the novel because they live in this world that's not aspirational, but still operates on this completely different dynamic than ours.

I was in Berlin at a literary festival there, this homosexuality in literature festival, that had brought in queer authors from all over the world. It was so extraordinary. It was like the United Nations of Homosexuality, where every country was represented by a different author. We were all on panels together, and spoke, and I just spent a week doing this. I heard from queer authors from Russia, from Turkey, from Iran, so many authors were talking about queer persecution, about publishers being seized by the government because they published queer content. All these tragedies and all of this oppression, and then I started to talk about my experience in Canada with When Everything Feels Like the Movies and some of the censorship that I faced, and then I also talked about being more advanced than some of these other countries that are talking about gays literally getting bound and thrown off cliffs. We're certainly not perfect in Canada, but we have progressed quite far. We've achieved a level of equality that many other countries don't have. So I started to talk about how equality shouldn't mean homogenization. Acceptance and progress for gay people shouldn't mean that we have to be like heteronormative culture, or that queer culture has to blend with heteronormative culture. I wrote Kens really to show what a post-gay world looks like, but I filled it with language that is so identifiably queer and scenes and situations and characters that are really rooted in queer culture, because I think it's really important to strike the balance between progress and the rich and fabulous history of queerness.

At times it felt—and I don't know if this is an intentional choice—LGBT identities can be treated as trendy, or commodified without necessarily progress happening.

Right, like the gay accessory, or the gay best friend. I hear that all the time. With straight women who are allies who are like, "Oh, I'm hanging out with my gays," so homosexuals are like a product. I definitely have a bit of fun with that.

Your book gets really dark. Heathers and a lot of your other inspirations were also really dark, but were you ever concerned with crossing a line?

Yes. Believe it or not, I'm not a shock jock. I really don't like causing controversy. It's not something that I seek. I have found that I'm naturally out of sync with this world and what society considers right and wrong. I'm constantly doing a lot of self-censorship and trying to not dull my ideas or erase them, but to hone my ideas or craft them in a way that is accessible to people, because I don't really have a good gauge for how people are going to react. Ultimately I have something that I'm trying to say. I'm trying to bring attention to certain issues. I never want it to be superficial. I want the significance to come through. But the dark aspect, like the mass teen suicide trend that starts, I was inspired directly by this world. There's that Blue Whale Suicide Game, I'm not sure if you've heard of that.

No.

It's this social media phenomenon where it's like a game that you play, and you follow a series of tasks, and the last task culminates in your suicide. [N.B: the origins and impacts of this game are ambiguous and differ between news sources.] There are hundreds of deaths attributed to this phenomenon, and there's a huge rise in teen suicide in the age of social media. I definitely think that the pressure that kids are facing on the internet plays into this. And also we're in this competitive world on social media, and so we compete with everything, every aspect of our lives. So what if we were competing with our deaths? That was my way of taking it to the extreme, to make us have a look at our own insatiable need to be recognized for everything.

I don't give away spoilers in this interview, but the fate of Brad was also hard to read in the context of the book.

Yeah. [pauses] I put that scene in the way that I did because I think the reality of those situations are so shocking and so immediate. I remember watching the video [similar to the incident that appears in the book]. I saw the headline, I clicked the link, I watched the video, and it was like being hit by a truck. It just felt so surreal, and so intense, and so emotionally overwhelming, and so shocking. I was so jolted by it. I decided it was important I write this chapter in a way that is just so shocking and that no one is expecting because I fear that the more terror that we see, the more apathy we see from our government on these issues, the more desensitized we become. I don't think that we're any less horrified than we were before, but I do think we are less shocked. I think the power of satire is to serve as an electric shock from the page, to remind you that this not something that you should scroll past, or that should become common to you. You should never get used to this. It should always be a jolt to your system.

So much has happened between the time between writing your last book and the writing with this one, specifically with your career, and the attention you've been getting. Having been the subject of think pieces and op-eds, did that affect your creative process at all?

You know, it didn't change my creative process. I feel like I've always just gone back to writing and being alone and finding a space within myself and finding a space in this world to create and that's what I did with When Everything Feels Like the Movies and that's what I did with Kens. I thought it was going to be different because I thought I was different, and of course I'm always different, I'm a different person every day I think. But what I found is it was very similar. It took a while to get this book published. I wrote the first draft in 2015, and sent it to my agent, and then started sending it out to editors. Because it's such a unique book, there aren't many comparative titles in young adult publishing right now. There's more film references than book references. I think that was maybe a concern to some editors. I went through this whole ritual of rejection, of failure, of feeling like maybe this isn't my next book, and struggling to place it in the market. And then I got the yes. Which is the same thing that happened with When Everything Feels Like the Movies. You get a million nos, and then one person says yes and changes everything.

Who do you hope reads this book?

It's interesting, because obviously I write it for a young market. Teenagers. But I recently recorded the audiobook, and I'm the voice actor on the audiobook, and the sound technician in the studio with me was a straight man in his fifties. He was laughing his head off as I was performing the book, and he told me he was going to buy it for people for Christmas. He was like, "I know I'm not your target audience, but I really appreciate your work." I always hope to get that guy. To get the person you don't expect and you're surprised they're interested in the work, and it affects them in a special way.

I know you said this isn't a direct Heathers remake, but there are times when Blaine is described as having Jack Nicholson eyebrows. Did you imagine Christian Slater when you were writing him?

Oh, I always imagine Christian Slater, are you kidding me?