The reunion tale is a familiar feel-good adoption story—a satisfying quest narrative in which an adoptee overcomes all the odds and, in the end, triumphs in finding the truth. But for adoptees and their families, both adopted and birth, the story doesn’t actually end there. A new crop of adoptee writers is exploring what happens after the reunion and challenging the assumption that truth is something that can ever be fully known.

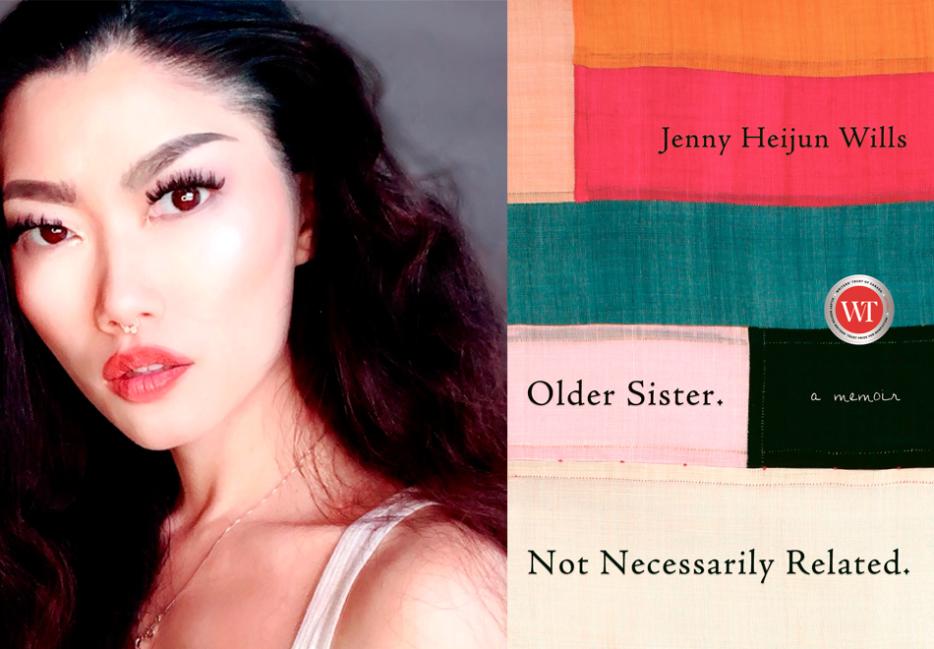

Jenny Heijun Wills was born in Seoul, South Korea. She was adopted by a white family, whereupon she was issued a temporary passport, sent on a flight to Canada as an infant and raised in Southern Ontario, with another name. As an adult, Wills navigated the post-adoption system, found her Korean kin and discovered her name at birth, Heijun. Her memoir, Older Sister. Not Necessarily Related (McClelland & Stewart) tells the extraordinary story of her return to Korea to meet and try to forge a relationship with her Korean family, and how she painstakingly pieces together a sense of identity and connection to her ancestral past from what was lost and found.

Yet the path to reclamation and understanding is fraught. It’s a different culture, she doesn’t speak the language and she, and her entire family, must face their own traumas as a result of the separation. In lyrical prose that’s both candid and compelling, Wills delves deeply into the often-heartbreaking complexities of transracial adoption and her lived experience of its long-lasting impact.

I know full well the impact of family separation and intergenerational trauma as a post-reunion adoptee myself, and as such this interview is a sharing of common ground and mutual understanding. At times during our chat I could feel us both nodding in agreement over the phone line. At the same time, I’m a transcultural adoptee who grew up looking passably similar to my adopted family, and I appreciated the opportunity to learn more about Wills’s experience as a transracial adoptee.

Recently, Older Sister. Not Necessarily Related was named to the 2019 shortlist for The Hilary Weston Writers’ Trust Prize for Non-Fiction. Wills works as an associate professor at the University of Winnipeg.

Suzanne Alyssa Andrew: As an adoptee myself, I know it can be difficult for adoptees to talk about their experiences. What did it take for you to come to the writing of this book, and what was the process like for you?

Jenny Heijun Wills: All of my scholarly writing has been in the field of race, and more specifically Asian adoption literatures or transracial adoption literatures. It was the guidance of those amazing books that started me down this pathway, including memoirs like Jane Jeong Trenka’s The Language of Blood and novels like Chang-Rae Lee’s A Gesture Life and Larissa Lai’s When Fox is a Thousand. When I began writing this book I was on sabbatical in Palo Alto, California and it was the first time since my reunion with my Korean birth/first family that I had some time off. It was having that time to sit with some of my experiences that motivated me to write.

When you began to write, did you find you had a momentum with it?

Yes, I couldn’t help myself. People ask me, “Was there catharsis, or a therapeutic process?” I didn’t feel it was therapeutic as I was writing, but it does allow me some sense of emotional relief when I read my story now.

When you were in Toronto in early September you had an opportunity to teach a writing workshop to a group of adult adoptees. How did that go?

It was inspiring, because the beauty, as you know, of being in conversation with other adopted people is that for the most part you can take for granted that they understand the core of where you’re coming from. You don’t have to start from the beginning and articulate adoption always comes from a starting point of grief, a trauma, a pain—that it doesn’t start off as something that’s celebratory, even if for some people it becomes that. It was really nice to have an opportunity to talk about writing, genre and themes of anger and expression.

It feels like more adoptees are writing about their experiences and I think that’s helpful. What was your goal with the workshop?

For the Koffler Centre that hosted my launch in Toronto, part of the series of events was providing a writing workshop and when they told me they’d reached out to adult adoptees I was very touched they had thought of that. It’s really unique for an organization to have that sensitivity. One of the great outcomes of the workshop is confirmation that people already are writing, maybe not with the ambition of publishing, but they are working on these creative expressions of their experiences, which is so exciting to me.

One of the things we talked about is the difficulty for adoptee writers to fit within genres of memoir or creative non-fiction or life writing because of the expectation of truth telling that comes with those forms, and as you know, the idea of truth is so abstract, amorphous and even pernicious to people like us. We talked about how adoptees can be part of a movement that’s challenging expectations of genre; and how we can accept writers who are telling their version of the truth at that particular moment because truth is temporal for some adoptees. How, as readers and audiences, might we be willing to let go of some of those demands for a concrete version of truth?

I find that fascinating, because for so many of us, certain details are just not available.

Yes, not available, or they change what the story is midway into your life, so all of a sudden, you’re born on a different day and in a different place, with a different name. Identity is proven to be so potentially inconsistent.

One of the details I find especially poignant in your book, because I share this experience, is finding ways to discover, reclaim your birth name and pronounce it.

That’s a big thing. Names are so meaningful to us but we also know they’re insignificant. It’s such a paradox. My birth name, Heijun, makes me both happy and sad because I think it’s a beautiful name but it makes me sad because in Korean culture often siblings will share the first syllable of their names. Korean names are typically two syllables long and siblings will have the same first syllable. I don’t share a first syllable with any of my siblings. It’s a reminder I was never meant to be fully part of that family.

You write when you moved to Toronto to study you were learning to be a woman of colour. When you were growing up with your adopted parents did you feel a sense of pressure to try to be like them?

I felt a self-imposed anxiety over being physically different from everyone in my world, not just my parents and my sister. Somehow, I felt it wasn’t a comfortable topic of conversation either. My parents adopted me in the assimilation era of transnational and transracial adoption where it was considered good adoptive parenting to try to erase racial and ethnic differences. Yet I always felt drawn to my own Korean-Canadian community, if I can claim to be part of it, or Asian Canadians. The struggle was when I arrived in Toronto it became apparent having not been raised in a Korean-Canadian family also meant I would never fully be included within that community either. They’d always speak Korean and I don’t speak Korean. It’s another reminder of being in between these cultures.

I was amazed by the way you travelled to South Korea and learned about your culture and worked to learn the language and immerse yourself in it.

I tried to. If you asked my Korean family they would say that I have not made any progress at all. I haven’t. I’m very unskilled in Korean language.

That’s such a challenge. When I visit my Ukrainian-Canadian family I look exactly like them, but I don’t have the culture. It’s a really odd position to be in to look like people but, it’s like you were saying, I don’t have the skills.

It’s this discomfort of wanting something so badly and loving people so hard, but not fully understanding how, or why, beyond the obvious. That’s one of the things I try to work through in the book. There are things that we do in the name of loving people whom we actually don’t know beyond genetically. There’s so much pressure—on that love, on that language and to understand that culture—it’s almost like we find ourselves in these positions where we’re always made to feel a complicated relationship to them. Whether it’s because we’re overperforming or underperforming any of these things, it’s never just right.

There are all these challenges built in, like you having to talk to your Korean family through a translator. I had to talk with some of my elder Ukrainian relatives through translation and it’s awkward.

Absolutely. It’s wanting to have these intimate conversations before people die—conversations that are sometimes about things people are ashamed of, or that people haven’t confessed to other family members—and having to require a stranger. In Korea it’s also hierarchical in terms of class, age and gender, so sometimes translators are too ashamed to even ask the questions or say the things that need to be spoken. Then you realize their role of being a translator for you in this intimate and precious moment is impacted by their self-censorship because of the cultural way they’ve been raised but you haven’t. It’s so multi-layered.

Another thing a lot of adoptees share is being able to talk about feelings towards your adopted parents. That’s a complicated relationship too.

A lot of adoptee writers talk about having to protect the feelings of their adopted parents, waiting until their adoptive parents have died before they can write their memoirs, talk about these things or go on birth searches, and it sometimes saddens me that so often we’re put in a position where we’re protecting the fragility and feelings of those who were gifted the opportunity to protect us.

I think there are so many myths about the adoptee experience. Do you feel that?

Some of the canonical stories that we love the most are about orphans and adoptees who are able to, through resilience, succeed in fighting their condition. Anne of Green Gables, Harry Potter, all of these texts are about people who supposedly are parentless (but we also know that’s a myth sometimes) who are being saved. And this is too comfortable a narrative for people to give up.

What do you want people to know about the adoptee experience?

What I want people to know is that it’s not about whether adoption is good or bad or whether we should do it or not. It’s about needing to be more critical about the way we approach the stories we’re given and thinking about who’s representing those stories, and why we have such a cultural stake in protecting certain versions of those stories over others.

Also, there is some irony of being a memoirist who is adamant about privacy and the public not having free access to all of you. In my case because I’m a transracial adoptee my experience of being an adoptee has always been visible from the time I was a baby, and so with that came narratives, assumptions, questions and comments from strangers that remind you that you’re always under surveillance. It’s important for me to undertake this kind of work because I’m trying to reclaim how I’m looked at, talked about and how much is shared about me.

Do you mean that by writing the memoir you have the opportunity to control the narrative, and it’s your story to tell in your way?

Yes. I’m trying to have some sort of agency over what the assumptions are about my family’s past, both biological and adoptive. People make assumptions about our first families and their class and the gender dynamics and why they supposedly placed children for adoption. The assumption in the very first place is that they were the ones who chose to do it. That’s the first series of myths that need to be broken. But people also make assumptions about adoptive parents and their reproductive histories, their class, cultural intentions and religions. Part of my memoir points to some of those elements which are true for me in my personal experience, but a lot of them aren’t.

My editor once told me that my book is more about asking questions than providing answers, and I think she’s right. My life has been a series of questions, some answered, many not. I’ve come to understand that what is important to me isn’t finding a solution or solving a mystery. It’s finding the words to ask the questions that are important to me at any given time and being resilient enough to be okay when there is no response, when the response changes over time, and when the response is distressing or is, it turns out, a complete lie.