It was a silly idea in the first place, this two-word mantra, proper noun followed by verb, and like most silly ideas, it came to Jim Riswold in the middle of the night. But then, advertising is a silly business, and it was Riswold’s sense of irony that had led him here. By the time Bo ran over The Boz on Monday Night Football, Jordan was already on his way to becoming an icon, and Nike was in search of another Jordanesque figure to market its cross-training shoes. The company’s first choice, Riswold says, was the Raiders’ Howie Long. Riswold suggested there was a far better candidate on the same roster, someone who had what in advertising is known as a unique selling proposition.

“I’m always surprised by how big something as inconsequential as an advertisement can become,” Riswold tells me. “People like their sports heroes, and Bo was something new. A shiny new toy. That was the best example of how big these things can become.”

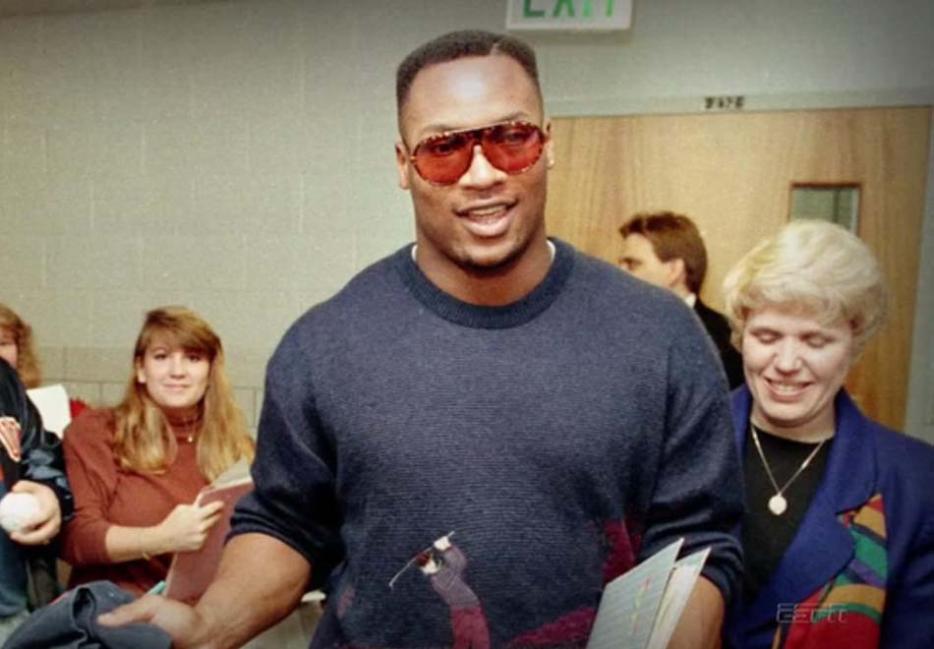

And so Riswold and his colleagues began toying with Bo’s maverick image, and Bo willingly played along; in Los Angeles, Nike placed the image of Bo, wearing shoulder pads and wielding a baseball bat, on print pages and billboards and on the sides of tall buildings. For the next couple of years, as the decade neared its end, as the Reagan presidency came to an end, Bo really was that huge. What we have now are stories that, with decades of wear, have already begun to feel like tall tales: of the time Bo scaled an outfield wall in pursuit of a fly ball until he was hovering sideways, seven feet off the ground; of the time Bo plowed over an All-Pro safety named Mike Harden, “as if [Harden] had been poleaxed,” according to one columnist; of the time Bo caught a base hit on a carom off the outfield wall and, while standing flat-footed, threw a ball three hundred feet and cut down Harold Reynolds at home plate; of the time Bo took a handoff against the Cincinnati Bengals, swept around the left side, cut back, and then was gone; of the numerous occasions a frustrated Bo snapped a wooden bat over his knee.

So why not, Riswold thought, in keeping with the ethic of the times, shape Bo as a larger-than-life figure, as a contemporary Paul Bunyan, as a man whose entire life seemed choreographed to near-perfection?

What an unusual name Bo has, Riswold thought, and he began brainstorming ideas with Nike executives—Beau Brummell, Bo Derek, Bo Schembechler, Bo Diddley—until that pronoun-verb combination came to him in his sleep that night.

Bo Knows.

That first iconic television ad, culminating with Bo playing a horrific guitar riff and Diddley himself delivering the line, “Bo, you don’t know Diddley,” aired during the All-Star game in 1989, which Jackson led off with a colossal home run (he was later named MVP). Riswold was watching at a bar in Portland, with several Nike colleagues. When the spot came on, the entire bar fell silent.

I think God is a Nike fan, Riswold muttered.

It was absurd what happened next, the way the catchphrase caught fire, the way Bo’s profile grew and mutated, until, for a short period, he was the most culturally recognizable athlete in the world, above even Michael Jordan himself. By 1990, Nike had surpassed Reebok in market share, and the company’s stock price had tripled. Riswold saw pirated T-shirts in Venice Beach: bo knows your mother. In The New Yorker magazine, a humor piece entitled “Bo Knows Fiction” imagined Bo’s public wrestling with a typewriter: “Then Bo sits back, exhales, and unzips his warm-up jacket, which has ‘Smith-Corona’ stitched over one pocket and ‘JUST TYPE IT’ in large letters across his broad back.” In Sports Illustrated, Leigh Montville began: “I report today on the operation. Bo successfully delivered a seven-pound, three-ounce baby girl this morning at a hospital in a small town in Alabama. . . . ‘Bo knows obstetrics,’ I tell the home office.”

The ads grew more self-referential as Bo got bigger and bigger, as he continued to improve both his baseball and football skills, and as our perception of the outsized era we’d come through slowly dawned on us. The eighties ended, and the nineties commenced, and perhaps we all knew, deep down, that this campaign was unsustainable: On January 13, 1991, during a divisional playoff game against the Bengals, Bo took a pitch and ran right and then, instead of cutting out of bounds, cut back one last time before he was taken down from behind by a linebacker named Kevin Walker, fighting like hell all the way.

In the midst of the push and pull, Bo’s hip was yanked out of its socket. Bo’s doctor told him if it were anyone else, his leg would have snapped like a dry twig—the irony being that a broken leg would have healed within months. He would make a brief comeback in baseball with the Chicago White Sox, but even after surgery, the hip would never be the same. “The gods of sports decided to punish Bo because he came to close to them, had reached the brink of being a god himself,” wrote his biographer, Dick Schaap.

Nike was deeply invested in Bo by then, and America was invested in Bo as the manifestation of its outsized dreams, and Riswold began writing subversive ads that pierced the myth of Bo, and the myth of Nike, and the commercialism and hype and immoderation of the Reagan era (these days, Riswold says, the conglomerate the Nike has become would never permit the same self-referential cheekiness). In one of the last great ads, from the summer of 1991, Bo cuts off a song-and-dance routine, declaring, “I’m an athlete, not an actor.” And then, in the midst of a workout, as the music cues once more, Bo breaks through the fourth wall, crying out to the Nike logo, “You know I don’t have time for this,” before George Foreman, huckster and infomercial pitchman sui generis, takes his place.

So it was: Within the span of a decade, Bo’s superpowers bloomed and wilted. And yet by then, it was too late. The monster Riswold had created—sports as cult of personality—was slouching out of its cage, to be reborn, over and over again.

“All the athletes today grew up with these commercials, and they want them,” Riswold tells me. “But the world is more cynical, and with good reason. It’s been done before. And the Michaels and Bos of the world don’t come around that often.”

From BIGGER THAN THE GAME: Bo, Boz, the Punky QB, and How the ’80s Created the Modern Athlete by Michael Weinreb. Reprinted by arrangement with Gotham Books, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC. Copyright © 2010 by Michael Weinreb.