According to Sigmund Freud, the human psyche is divided into three elements: the id, super-ego, and ego. The id represents our uncontrolled and instinctual desires, the super-ego our moral conscience, and the ego mediates those two pulling forces.

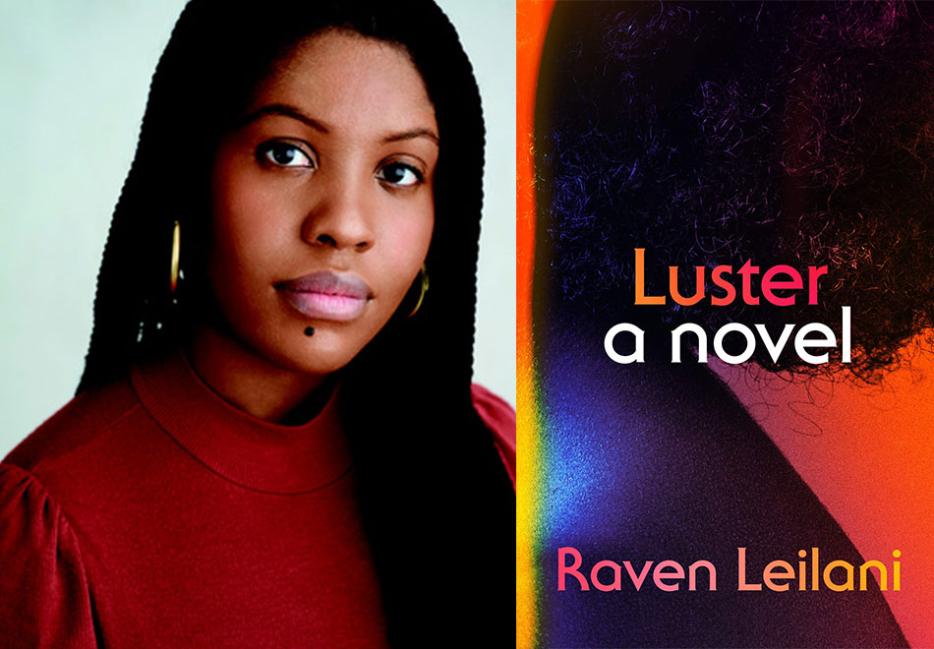

In her debut novel Luster (Bond Street Books), Brooklyn-based writer Raven Leilani plunges the reader inside the mind of a 23-year-old Black woman whose life is controlled by her id.

Edie’s an aspiring painter who avoids painting, instead working in a low-level position at an editorial publishing house in New York City. She falls into a relationship with Eric, a white man twice her age who is an open-ish marriage. After Edie can no longer afford the rent of her mice-infested apartment, she moves to suburban New Jersey to live with Eric, his wife Rebecca, and their Black preteen adopted daughter, Akila.

Luster, as the title suggests, is lush with vivid references to sex. At the publishing house, Edie calls herself, matter-of-factly, the “office slut” and describes hooking up with various colleagues across departments: “Jerry who is acquiring all the cancer-centric YA, making bank and soft love to me in the conference room,” or, “Michelle from legal sitting on the copier, nylons slung around her neck as fluorescents flicker overhead.” With sex as the backdrop, the book brilliantly explores Black womanhood, suburban surveillance, millennial capitalism, micro-aggressions, and the complicated nature of interracial relationships.

Leilani is careful when she speaks, frequently stopping mid-sentence to pause and regroup before proceeding. When we chat, she’s outside of her apartment in Brooklyn, where the high-pitched beeps of reversing trucks, the static of wind and other city sounds leak into our phone call.

Samantha Edwards: Edie has such a singular voice that’s incredibly funny and observant, but can also be really self-deprecating and dark. How did you develop her character?

Raven Leilani: The building blocks of Edie was, “How do I depict a young Black woman who yearns?” She’s a woman who is led through the world by her id. I don't really move through the world like that. There's a freedom and almost an element of wish fulfillment in depicting a Black woman who is guided by her own id. It was important for me to write a Black girl who was free. It's weird to say free because on the page, you can see the constraints, one being the fact that a lot of the action is happening in Edie’s mind. But at least in the sanctuary of her mind, I wanted to be candid about how she feels and what she wants.

The observational aspect of the book comes from two things: the fact that Edie is a Black woman and the certain kind of studiousness that you need to survive. The other part is that she's an aspiring artist, and I think a fundamental part of art is data collection. And that sounds extremely unsexy, right? But a lot of art, especially the art I gravitate to, is in the business of trying to accurately reflect a specific reality.

Edie yearns for sex and touch. Why was it important to make that such a core part of her person?

I felt like to do anything less would be to not allow her the space to be human. There's a temptation in writing and in life to be self-protective, to be aloof, and to be stoic. I know those people exist and that kind of writing exists, but I wanted to write towards vulnerability. I think it’s always a vulnerable thing to be overt in how much you care.

A lot of Black women are called upon to bear their pain well. And that feels inhumane. I wanted to write a Black woman who is not only not bearing what she's going through well, but who responds in a human way. She gets hurt, and she also wants comeuppance. Let me try and articulate this. We talk a lot about unlikable women, and I think what we're really talking about is fallible women. I wanted to show what it looks like when you care deeply, and the way that that manifests isn't just as a virtuous person who lives by their feelings. There's an element of caring so deeply that you are paralyzed. I think to be human is to be unruly, to be a person who yearns and can be hurt. And that was important for me, to show a Black woman who was not stoic in how she bears her loss.

I found the differences between how Edie and her Black coworker Aria navigated their very white workplace so interesting. Aria says she’s willing to "shuck and jive until the room I’m in is at the top” and to conform to her white coworkers' expectations, while Edie has no interest in performing in that way. She seems to revel in being a slacker. What did you want to show in their relationship?

I wanted to show that both of these Black women in this professional space are attempting to survive. They just have very, very different tactics around that survival. Aria has opted for perfectionism and hyper-curation. Edie's response is one of refusal. I think both are human responses. There's one way to read this that’s a judgment on how Aria has chosen to present herself. I was trying to point out how when you are trying to advance and survive as a Black woman, you understand that your margin for error is thin.

I also wanted to talk about how this environment absolutely impedes a camaraderie that perhaps should exist between these women. When their environment indulges tokenism, it naturally pits these two women against each other. They're two different women, absolutely, but even Edie's response to seeing Aria is that she felt relief. She also finds that relief with Akila later on in the book too.

I really loved how the relationship between Edie and Akila progressed throughout the book. At first Akila feels kind of uneasy around Edie’s presence, basically saying, “Don’t mess this up for me,” but eventually they do build that camaraderie.

This book is very much about isolation and solitude, and loneliness that is exacerbated when you're in the business of projecting an image and managing the perceptions of other people around you. Akila lives in an environment which cannot adequately witness her. She lives in the suburbs and is being surveilled, and that surveillance can quickly become violent.

Akila is searching for belonging and not truly finding it. She's not doing well socially. She has been bounced around, she's been through a couple of homes and her primary mission is to preserve the stability she finally has and Edie is a threat to that. But Edie herself is also grappling with a kind of instability. So you have two Black women who are fighting for stability and fighting for a place where they will be seen. I thought it was important to show two Black women taking comfort in each other and witnessing each other.

As they get closer, we get to see more layers of Akila, like that she's really into writing fan fiction, comic books, and video games. Edie helps her make a Comic-Con costume and I thought that was so endearing. And the Comic-Con scenes were so lucid. Have you ever been to a Comic-Con?

The reason Comic-Con is in the book is because I love it. I feel like the very first way I knew how to interact with anything was as a fan. I feel like fandom for me is an earnest act. There are moments throughout the book where I got to show a Black woman engaged in a thing that she earnestly loves. For Edie it’s disco, and with Akila it's Comic-Con. All of this sort of geek ephemera is close to me.

I've been to a handful of Comic-Cons, but never to San Diego, which is a bummer and I need to fix that. There’s nothing really like attending a con and feeling that enthusiasm and communal energy, and also seeing other fans who dare enough to be earnest in their overt appreciation for these imagined worlds. That is so beautiful to me. I wanted to specifically talk about that on the page with a Black woman because I wanted there to be joy in this book.

There’s a lot of sexual joy in the book, but obviously that’s different than the joy from fandom. Akila’s fandom is like pure joy, and there’s no weird power dynamics behind it. What kind of stuff are you a fan of?

Oh man, I'm a fan of so many things. My brother gave me his comics before he moved out and I still have them. They're in a trunk under my bed. I don't even indulge the kind of rivalry between DC and Marvel. I love them both. I grew up watching anime and playing JRPGs, which are Japanese role-playing games. When I was younger, I loved getting locked into those intricately built worlds.

It’s interesting you say that, because when Edie and Akila get closer and start playing video games together, Akila kind of disses Edie for not getting as involved with some of the side characters or just missing parts of the story.

That's right. I'm so glad you noticed that. There are so many different kinds of gamers. There are the gamers who want Call of Duty, where you can go in and get your rounds off. But then there are those who want a game where you have to talk to villagers like three times to get the thing that you need, games where you have to exhaust the environment in order to advance. I gravitate more towards the games that have a story.

I do think there's something to be said about two Black women finding comfort in each other through the imagined worlds in which they have to inhabit these avatars. It's my fandom manifesting for sure. Perhaps it’s also me as a 29-year-old and how a lot of us have grown to relate to people through a digital medium, whether it’s online dating or your headset in Call of Duty.

How does it feel to release this book in this current “moment”? I’m putting air quotes around moment because racism has been around forever, but I think reading this book now, there are certain themes the book touches on, like police violence or acknowledging micro-aggressions, that feel so urgent right now.

Like you were saying, racism isn’t new and what we’re seeing now is perhaps not new. What’s new is that we have the technology to see it in a totally different way. I have talked to older people in my family because there’s this feeling of reckoning, that something feels different. I’ve said to them, “Before I get my hopes up, can you let me know, does this feel unprecedented in terms of the response to it?” Even older people in my family do feel that something is different, especially around police brutality. The thing is, as a Black writer I was not necessarily writing towards any particular grand statement around racism. I wrote this book as a Black woman who is writing about Black women. In particular, with Edie, I was just reporting on what I saw in my own life, the way I feel my own body is in peril and the way Edie’s body is in peril.

You don’t necessarily want your book to be relevant in the way that it is. You would hope that you could point to what you’ve written and it would be history. It would be a moment that is distant and illegible. But I do think that the canon of Black writers who have written about what it is like to live and try and survive while Black is a large and excellent canon. In writing about these issues, I just did my best to tell a specific story. The story just happens to be one that takes place in the consciousness of a Black woman, and that consciousness is informed by an environment that is racist, sexist, and capitalist.

You and Edie share some life experiences—you are both painters, you’ve both worked in publishing and at Postmates. And because this is your debut, were you ever nervous or concerned that people would conflate you with Edie?

I feel like that is a concern that a lot of writers of colour have. I don’t imagine that you get as many autofictive questions when you’re a white author. Truly though, I wasn’t particularly concerned. There is a lot of me in the book, but it’s absolutely not autofiction. There are a lot of direct lines you could draw from my life, but I couldn’t think about that reflection while I was writing. I think that would have limited me and would have put fear in the writing.

As you might have gathered on this call, I truly struggle in real time to articulate precisely what I mean. That is a major frustration for me. On the page, I feel like I have more control than I do in any area of my life. Because of that, I have the freedom to write towards the dark and the dirty.

I have a friend who says that the book is my id and I am the ego. I think that is correct. In some ways, I’m writing a letter to my own self, like, “Oh my god, don’t do that.” But there’s a part of me that tried to imbue a freedom in this character that I absolutely as a real person don’t think I have. I’m actually quite subdued. I’m severely introverted. The things I write versus who I am as a person are actually quite opposed. It’s interesting to release a thing into the world and then have people feel like they know who you are. But ultimately, I just think it’s really fucking cool that people are reading deeply enough where they care about that.