Is cultural imperialism the wrong phrase to describe Facebook’s purchase of WhatsApp? On the surface, it certainly sounds absurd. WhatsApp was, after all, yet another Silicon Valley company that was simply swallowed up by the Valley company par excellence. Typical Palo Alto incest, sure, but imperialism?

Yet, it was the term that leapt to mind as soon as I heard the news. Like millions of people, my family, a diaspora scattered across the globe, uses WhatsApp to stay in touch despite the immense geographic distances that separate us. Now that a company like Facebook owns it, it feels a bit like your favourite band selling out. Even if, in truth, there never really was any pure state to begin with, it still feels odd that a thing that was an intimate part of your life has now been sucked up into the contemporary emblem of the evil empire.

But if we felt a similar kind of “death of indie” with the purchases of Flickr, Instagram, and others, WhatsApp is unique in that its explosive growth has come in large part because of people, like my family, who are from what we tend to refer to as “emerging markets.” If WhatsApp is ostensibly just one more American company buying another, the optics are different because the user base is full of non-Western, non-white people. Just because it isn’t imperialism per se, it doesn’t mean it can’t give off uncomfortable echoes of it.

Consider this statistic: eight out of ten of the world’s top Internet properties are Made in the U.S.A—and 81% of their users are outside the U.S. That means most of the globe’s most popular online infrastructure—Google, Facebook, Twitter, and so on—is the product of American culture.

Whether or not you find that troubling depends on what you think software is. If you believe something like Facebook is a neutral platform that allows people to connect in the terms of their choosing, then the wide availability of a tool for communicating is a boon. Undoubtedly, there is something to this idea. If Twitter is also just one more company cooked up by dreamy, white Californians, then its popularity amongst African Americans, Turks, and countless other communities across the world suggests that, even if we assume there’s an inherent ideology to software, it can at least be put to uses its creators may not have imagined. That old question by Audre Lorde—can you use the master’s tools to take down the master’s house?—is complicated by the way in which digital can at least appear to put the “means of production” into everyday people’s hands.

On the other hand, it’s worth asking if there’s something beneath the idea of “connecting” itself. One of the truly strange and brilliant things about social networking is the way it has collapsed the line between communication and publishing, turning the act of chatting with a friend or setting up a meeting into an often public display. Sometimes that’s great, as it creates a space for public exchange, but sometimes it’s hard to imagine any reason it exists except to track those conversations—and sell ads.

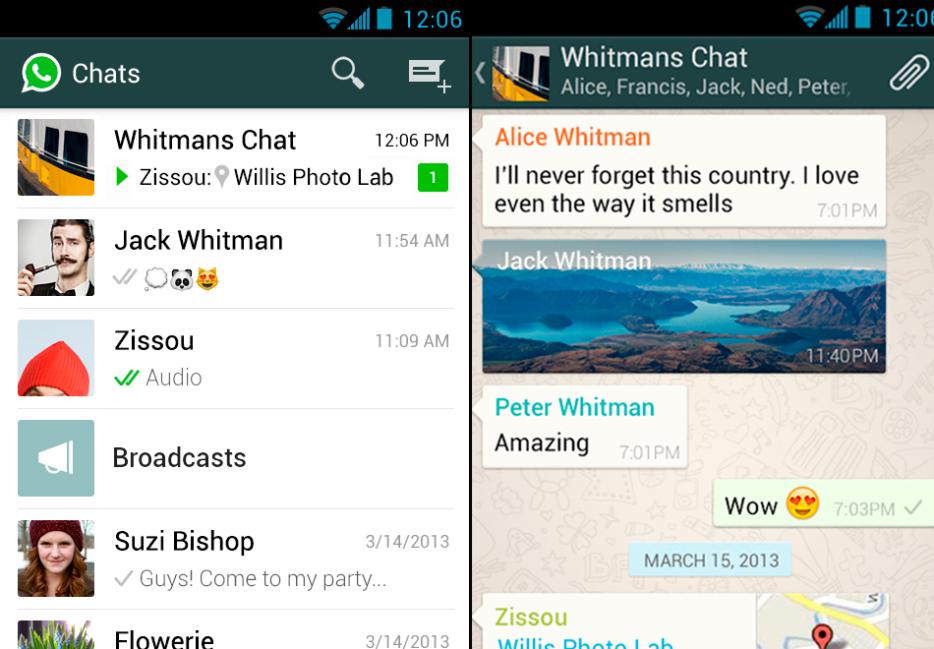

Part of the reason WhatsApp is thus such an odd choice for Facebook is that, by its very nature, it is closed to the usual ad-based model of social networks. The emoji-filled group chats that have become so central to the service are, in theory, hidden from the prying eyes of marketers. It’s almost anachronistic: you pay 99 cents a year to talk to people in private, rather than paying nothing to “connect” and be tracked in the process.

Although WhatsApp has claimed its structure won’t change, it’s hard to believe that, two years from now, the service will remain the same. Even if Facebook continues the for-pay private model of conversation, it will have an obvious economic incentive to pull users into its broader network and encourage them to connect there. Oh, you want the latest and best features? Well, you better get on Facebook.

In that sense, the cultural imperialism argument becomes a bit harder to ignore. In The Interface Effect, Alexander Galloway argues that you can look at software as something neutral, or something that shapes your relation to the world—and that both views are wrong. Instead, Galloway suggests, software and interfaces are almost internally referential, creating their own logic. We have analogies for online discourse—the public square, chat rooms, letter writing—but none of them quite encompass the fundamental and strange newness of what we do online. Once you impose the software, you impose its logic. In a weird way, it’s almost as if it’s not what you do with Facebook, but that you use it at all.

It’s certainly true that nothing is ever black and white. When, earlier this week, my cousins from India took to WhatsApp to wish me happy birthday, I’m not sure that within those words, bits, or pixels was hidden the entirety of post-Fordist capitalism. The question to keep in mind with modern colonialism, though, is not whether or not something represents direct oppression, but if it obscures alternatives. And if WhatsApp, like so many other things, is subsumed into an ideology from Palo Alto, forming one more way in which the Western is the norm, it behooves us to ask what is lost and what is gained when we all “connect” in the same way.