What do we actually want social media to do? It’s a testament to how deeply Facebook et al. have penetrated our lives that the question itself sounds strange. To ask “What’s the hot new thing in social media?” sounds reasonable. But less than a decade into its existence, “What do we want social media to do?” already sounds like a question asked by an alien.

It sounds odd, in part, because it presumes we have (or ever even had) a choice. But I ask now because the tea leaves of the Internet seem to be at least temporarily resolving into something clear: we’re about to embark on the next phase of social media. Facebook, Twitter, and others are not only becoming more like each other, but also more similar to the media they sought to replace. Dedicated apps are about to be the new normal, as the many functions of social networks splinter off into smaller chunks. New forms are emerging, from ephemeral messaging to apps just for two. But hovering above it all, another question: what does a world in which social relations are structured by the vision of Silicon Valley actually look like?

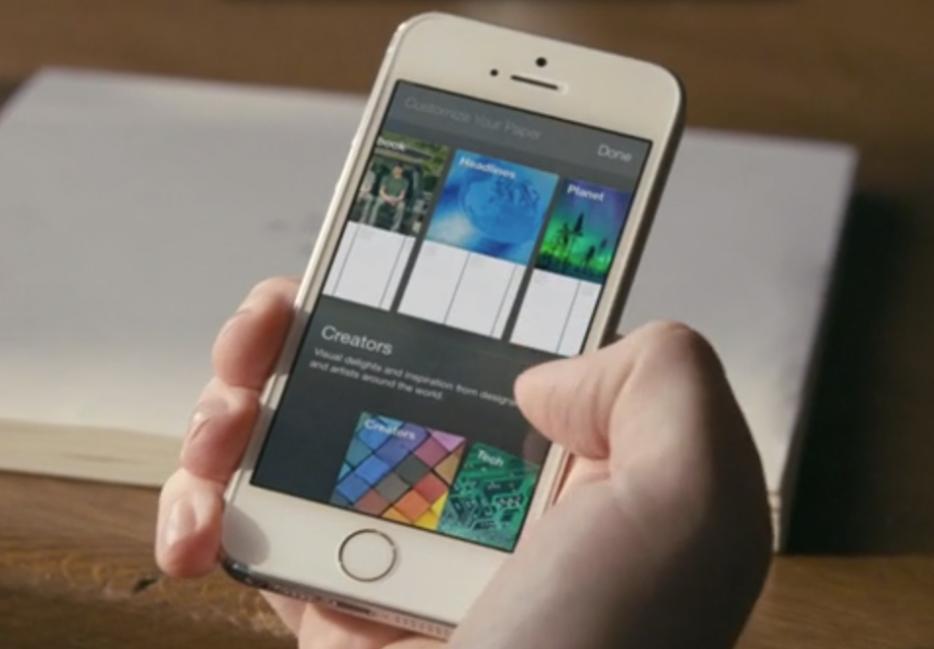

For a while, the tech world was so obsessed with social that the word became a noun. Now, everything is social—or, at least, social in the terms of the Valley: shareable, trackable, able to be “liked.” Now, the concern is not just making things social, but, rather, making social things more like media. That’s the mentality behind Facebook Paper, the glossy new mobile app from Zuckerberg and Co. that makes your newsfeed feel like a magazine app. It’s echoed by aforthcoming redesign from Twitter that makes it more like Facebook—i.e., more like a destination than an ever-flowing stream.

These changes are less about being “disruptive” than becoming the norm. The aim, as always, is to become your default entry into the web—except the difference now is, instead of people simply saying “social media will be the new newspaper,” it’s actually true. As Derek Thompson at The Atlantic outlines, many people currently treat Facebook or Twitter the way they once treated the Globe and Mail or the New York Times, making it the first thing they read each morning—a change made all the more remarkable by the timespan in which it occurred.

Yet, in another way, these shifts represent the social network as media object: a kind of genre or form, with its own stylistic, mechanical, and ideological uniqueness. That Facebook Paper has been described as having a magazine-like appearance is no coincidence, because that’s exactly the desire: to re-conceive what we call “media” as a thing composed of mainstream news and your friend’s baby pictures.

At the same time, however, we’re also surprisingly seeing the opposite trend. According to some, such as TechCrunch’s MG Siegler, the age of the social network is coming to an end. He’s got a point: as the many functions of social networks splinter off into smaller, dedicated apps, instead of using Facebook for everything from news to sharing pictures to instant message, we instead get Paper, Instagram, Vine, or Whatsapp. Twitter is pondering a messaging app of its own, while other companies like Snapchat are popularizing new types of social, such as ephemeral messaging. We’ve even seen the rise of anonymous apps like Whisper and Secret that let people voice ideas without attaching their names to them, evoking a return to the less formal, rigid ways of the early web. What were once subsumed by umbrella social networks are breaking off, mostly because as practices become more and more mainstream and formalized, they require their own spaces and ways to access them.

But what, then, to make of this seemingly contradictory split between social-media-as-everything and the focused, single-purpose social media app? In one sense it represents the tension in the desires of companies such as Twitter and Facebook—a division between wanting to be the go-to digital destination, and a wish to be the infrastructure for other services. But I’d argue part of it comes down to users increasingly realizing that the services they’re using were invented in university dorms or boardrooms where everyone wore Cons and khakis. To wit, the schizophrenic nature of modern apps is a result of the fact that the social expectations that came baked into Facebook or Twitter may not have made much sense in the first place.

Why, for example, have a social network in which you share the same things with your co-workers, your parents, friends you grew up with, and that friend-of-a-friend you met at a party last week? Similarly, the best thing about Twitter—that it mixes serious news and debate with jokes and day-to-day ephemera—is also its worst trait when it comes to finding a balance between utility and pleasure. It’s almost as if these things were never designed to be used by hundreds of millions people, and what we’re dealing with are the accidents of history.

That’s why we’re getting both trends at the same time from the same entities—because social media is such a strange, amorphous beast, at once both media and communication platform, fixed destination and dynamic network, a thing always at odds with itself. It’s the effect of rapid social and technological change being implemented at historically unprecedented rates; think about what it means that more than a billion people are using a service that didn’t exist ten years ago.

So when you return to the same question—what do we want social media to do?—you necessarily end up with a trickier question: what exactly is social media?

Some, like The New Inquiry editor Rob Horning suggest it would basically be unthinkable without capitalism—and that furthermore, social media represents modern economics’ most crystallized, pernicious form. In this view, social media is a historical invention meant to extract both information (to track and then sell things to you) and emotional labour (to keep you invested in the services). Social media, in effect, makes people in its own image, shaping individuals for the purpose of offering themselves up as consumers; it’s indenture masquerading as freedom.

I’m less cynical than that, if only slightly. Throughout history, significant changes have been engendered by the externalization of basic human connective tissue through media: writing/externalized thought, photography/sight, film/the moving image, and so on. Each of those various changes effected massive change, because taking a dimension of thought and turning it into an object or a thing outside the body has huge ramifications, and one need only think of the difference between a campfire story and a novel to understand why.

What social media does, however, and the reason it’s so messy, is externalize two things at once: communication and consumption. It turns connections between people into media objects, then publicizes and makes trackable their habits of consumption, even if the thing being “consumed” is other people. It’s for that reason that social media can simultaneously seem so liberating and pernicious, so practical and pointless, so free and yet so constrained.

So what do want social media to do? We want it to externalize and enable the good things: the connections with others, the lively public square, the humming pulse of the world. At the same time, we wish it could somehow evade the other side of things: the tracking, the personal branding, the fear of missing out, the pointless evasion.

Is such a thing possible, though? Only to the extent it is in other fields of human action. Can you walk down the street and only see the independent grocers, the Salvation Army, the food bank, and the fair trade coffee shop? Of course not. There’ll also be the Gap, Target, and the bank that not only holds the mortgages for all of those places, but whose parent company aggregates them into derivatives, too. The question regarding social media is actually the same as it is for the street: can you extricate the products of modernity from modernity itself? No. You can only fight to inch closer to the vision of the world you want, or carve out something resembling an ethical space for yourself. Sometimes that means abstaining, sometimes it means using things against the grain, and sometimes it means accepting that you can’t actually make a difference, so you may as well enjoy yourself along the way.

So, what do we want from social media? Maybe we’re asking the wrong question. Social media really has, in its own terms, “made things social.” It’s produced a sphere of action that not only externalizes social relations, but commodifies them, too. Now that it has become so deeply woven into everything good and bad about the contemporary world—and is, at the same time, poised to launch into an even more mystifying phase—maybe what we should be asking is much more basic and troubling: how, given a seemingly inexorable march toward social media ubiquity, are you going to choose to use it?