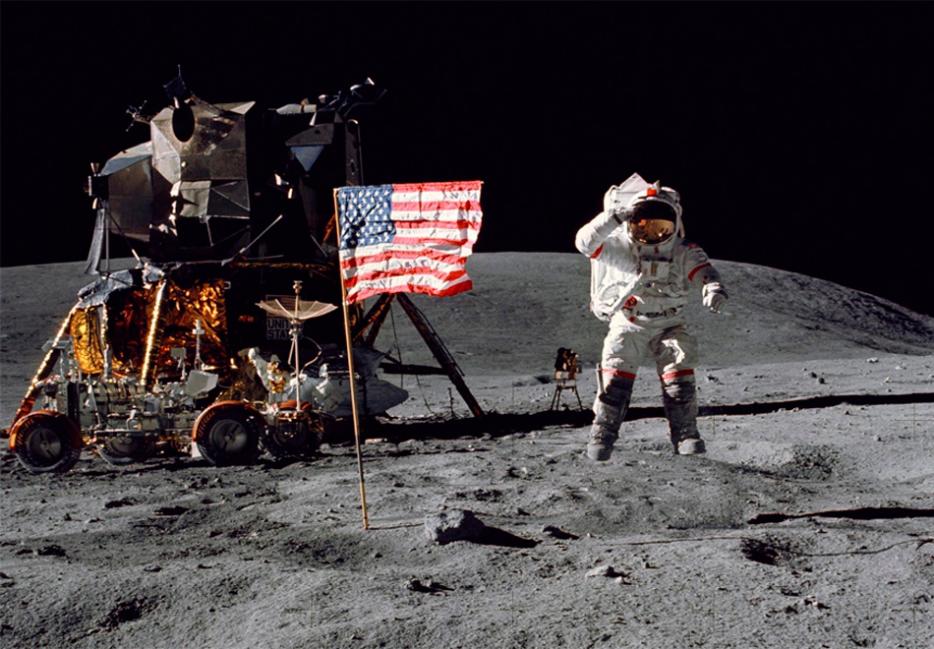

One of the people responsible for putting a man on the moon died last week at the age of 95. This is, in 2014, a common and not terribly newsworthy occurrence: the generation of men and women whose industry kept a dozen men safe from vacuum, radiation, and temperatures ranging from scalding to freezing is now succumbing to the mediocre ravages of time. The youngest living astronaut to have walked on the moon itself is older than Hitler’s invasion of Austria.

But John C. Houbolt deserves our attention, for at least a moment, because his contribution was important enough that it changed the direction of the US space program. As NASA tried to figure out, in the early 1960s, how it was going to meet President Kennedy’s goal of landing a man on the moon before 1970, Werner Von Braun was pretty sure he already knew the answers: he had, after all, been thinking about this stuff for some time.

The problem was Von Braun, whom the Americans had seconded with his enthusiastic consent at the end of World War II, didn’t want to build machines just to land a man on the moon. He wanted rockets that could also help the United States build space stations, and eventually put a man on Mars.

For Houbolt, the problem was much simpler: the president had given NASA an objective, and NASA should meet that objective as efficiently as possible. Where Von Braun wanted massive rockets, called “Nova,” capable of putting massive amounts of weight on the Moon’s surface, Houbolt suggested the simple two-man capsule that would become the Lunar Excursion Module—the kind that would eventually land on the Sea of Tranquility.

Houbolt’s proposal was simple, elegant, efficient, economical—and at first, an abomination to people like Von Braun and others at NASA who recognized it for what it was: a proposal to land a man on the moon, and nothing else. Houbolt was not patient with his critics: “Why is Nova, with its ponderous size simply just accepted, and why is a much less grandiose scheme involving rendezvous ostracized or put on the defensive?”

Houbolt won the day after a year of lobbying Von Braun, ever the German engineer, would eventually be convinced by the numbers), and the Apollo program just met Kennedy’s deadline. The thornier question is whether his critics were right, as well: the hardware developed for the Apollo program was mostly allowed to rust after the excitement of landing on the moon, and then the United States engaged in a generation-long detour into the Space Shuttle program. Meanwhile, SpaceX continues to make tentative progress towards the goal of reusable space rockets, meaning they might actually deliver on the promise the Shuttle was supposed to before I was born.

But, given that the US government’s current space program amounts to repurposing parts from the Space Shuttle program to build an Apollo-like rocket, arguing that choosing Hoboult’s vision over Von Braun’s led to America’s hiatus from space exploration is a stretch.

Sometimes we need to aim for the stars and make the biggest plans possible. But Houbolt’s contribution to NASA is a reminder that when you’re already aiming for the stars, having someone around to temper your grandiosity can be worthwhile.